Urban heat island

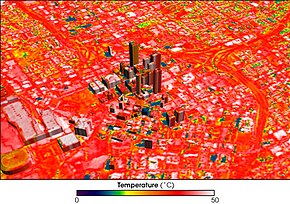

The main cause of the UHI effect is from the modification of land surfaces, while waste heat generated by energy usage is a secondary contributor.

"[14]: 2926 This relative warmth is caused by "heat trapping due to land use, the configuration and design of the built environment, including street layout and building size, the heat-absorbing properties of urban building materials, reduced ventilation, reduced greenery and water features, and domestic and industrial heat emissions generated directly from human activities".

[17][18] Studies have shown that diurnal variability is impacted by several factors including local climate and weather, seasonality, humidity, vegetation, surfaces, and materials in the built environment.

[22] Complex relationships between precipitation, vegetation, solar radiation, and surface materials in various local climate zones play interlocking roles that influence seasonal patterns of temperature variation in a particular urban heat island.

[27] The index does not consider values of or differences in wind-speed, humidity, or solar influx, which might influence perceived temperature or the operation of air conditioners.

[34] Pavements, parking lots, roads or, more generally speaking transport infrastructure, contribute significantly to the urban heat island effect.

One key risk is heatwaves in cities that are likely to affect half of the future global urban population, with negative impacts on human health and economic productivity.

In addition, the UHI creates during the day a local low pressure area where relatively moist air from its rural surroundings converges, possibly leading to more favorable conditions for cloud formation.

[52] The nighttime effect of UHIs can be particularly harmful during a heat wave, as it deprives urban residents of the cool relief found in rural areas during the night.

According to a study by Hyunkuk Cho of Yeungnam University, an increased number of days with extreme heat each year correlates to a decrease in student test scores.

Another study employing advanced statistical methods in Babol city, Iran, revealed a significant increase in Surface Urban Heat Island Intensity (SUHII) from 1985 to 2017, influenced by both geographic direction and time.

Hot pavement and rooftop surfaces transfer their excess heat to stormwater, which then drains into storm sewers and raises water temperatures as it is released into streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes.

This increase causes the fish species inhabiting the body of water to undergo thermal stress and shock due to the rapid change in temperature of their habitat.

Increased temperatures, causing warmer winter conditions, made the city more similar in climate to the more northerly wildland habitat of the species.

[71] Another consequence of urban heat islands is the increased energy required for air conditioning and refrigeration in cities that are in comparatively hot climates.

[72] Through the implementation of heat island reduction strategies, significant annual net energy savings have been calculated for northern locations such as Chicago, Salt Lake City, and Toronto.

The heat island effect can be counteracted slightly by using white or reflective materials to build houses, roofs, pavements, and roads, thus increasing the overall albedo of the city.

[78] In this way, it was planned to build urban settlements stretching over large areas, e.g. Kielce, Szczecin and Gdynia in Poland, Copenhagen in Denmark and Hamburg, Berlin and Kiel in Germany.

In comparison, additional tree cover reduced temperatures by 0.3 °C and solar panels by 0.5° C.[76] Relative to remedying the other sources of the problem, replacing dark roofing requires the least amount of investment for the most immediate return.

[84] A low albedo value, characteristic of black asphalt, absorbs a large percentage of solar heat creating warmer near-surface temperatures.

[103] When installed on roofs in dense urban areas, passive daytime radiative cooling panels can significantly lower outdoor surface temperatures at the pedestrian level.

Between the 1920s and the 1940s, researchers in the emerging field of local climatology or microscale meteorology in Europe, Mexico, India, Japan, and the United States pursued new methods to understand the phenomenon.

Some studies suggest that the effects of UHIs on health may be disproportionate, since the impacts may be unevenly distributed based on a variety of factors such as age,[59][108] ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

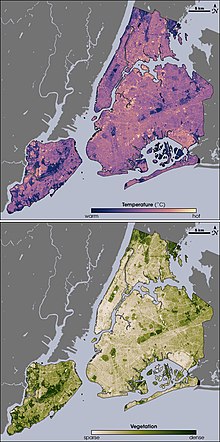

The city of New York determined that the cooling potential per area was highest for street trees, followed by living roofs, light covered surface, and open space planting.

[79] In a case study of the Los Angeles Basin in 1998, simulations showed that even when trees are not strategically placed in these urban heat islands, they can still aid in minimization of pollutants and energy reduction.

[122] Los Angeles has also begun to implement a Heat Action Plan to address the city's needs at a more granular level than the solutions provided by the state of California.

[123] In 2021, Climate Adaptation Planning Analysis (CAPA) received funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to conduct Heat Mapping across the United States.

A report by The Hindu highlights that metropolitan areas like Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Jaipur, Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and Kolkata have seen temperature differences ranging from 1°C to 6°C compared to their rural surroundings.

These urban heat islands not only increase the local temperatures but also exacerbate the impacts of heatwaves, leading to higher energy consumption for cooling and posing health risks to vulnerable populations.

[126] Mumbai, India's financial hub and one of the most densely populated cities globally, is significantly affected by the urban heat island effect.