Heat recovery ventilation

[1] A typical heat recovery system in buildings comprises a core unit, channels for fresh and exhaust air, and blower fans.

The specific equipment involved may be called an Energy Recovery Ventilator, also commonly referred to simply as an ERV.

ERV's must use power for a blower to overcome the pressure drop in the system, hence incurring a slight energy demand.

[4] A heat recovery system is designed to supply conditioned air to the occupied space to maintain a certain temperature.

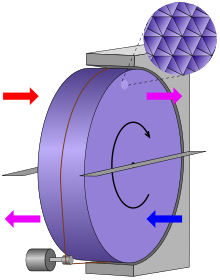

A rotating porous metallic wheel transfers thermal energy from one air stream to another by passing through each fluid alternately.

Desiccants transfer moisture through the process of adsorption which is predominately driven by the difference in the partial pressure of vapor within the opposing air-streams.

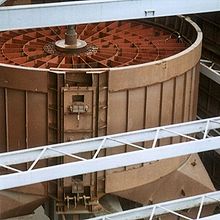

O’Connor et al.[9] studied the effect that a rotary thermal wheel has on the supply air flow rates into a building.

A computational model was created to simulate the effects of a rotary thermal wheel on air flow rates when incorporated into a commercial wind tower system.

These heat exchangers can be both introduced as a retrofit for increased energy savings and fresh air as well as an alternative to new construction.

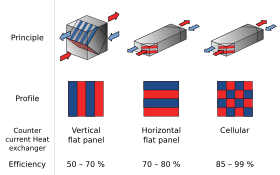

Due to the need to use multiple sections, fixed plate energy exchangers are often associated with high pressure drop and larger footprints.

[16] Mardiana et al.[17] integrated a fixed plate heat exchanger into a commercial wind tower, highlighting the advantages of this type of system as a means of zero energy ventilation which can be simply modified.

Full scale laboratory testing was undertaken in order to determine the effects and efficiency of the combined system.

A wind tower was integrated with a fixed plate heat exchanger and was mounted centrally in a sealed test room.

The results from this study indicate that the combination of a wind tower passive ventilation system and a fixed plate heat recovery device could provide an effective combined technology to recover waste heat from exhaust air and cool incoming warm air with zero energy demand.

Though no quantitative data for the ventilation rates within the test room was provided, it can be assumed that due to the high-pressure loss across the heat exchanger that these were significantly reduced from the standard operation of a wind tower.

This further enhances the suggestion that commercial wind towers provide a worthwhile alternative to mechanical ventilation, capable of supplying and exhausting air at the same time.

A CFD model of the passive house was created with the measurements taken from the sensors and weather station used as input data.

The model was run to calculate the effectiveness of the run-around system and the capabilities of the ground source heat pump.

No research has been conducted into the use of PCMs between two airstreams of different temperatures where continuous, instantaneous heat transfer can occur.

[16] Source:[16] Sensible and latent heat recovery Compact design Frost control available Mechanically driven, requiring energy input Air velocity Wheel Porosity High heat transfer coefficient No cross contamination Frost control possible Sensible and latent heat recovery Limited to two separate air streams Condensation build up Frost building up in cold climates Operating pressure Temperature Flow arrangement

No cross contamination Low pressure loss Compact design Heat recovery in two directions possible Internal fluid should match local climate conditions Contact time Arrangement/configuration Structure No cross contamination Low pressure loss Multiple sources of heat recovery Difficult to integrate into existing structures Low efficiency Cost Fluid type Heat source Offset peak energy demands No pressure loss No cross contamination No moving parts Long life cycle Expensive Not proven technology Difficulty in selecting appropriate material **Total energy exchange only available on hygroscopic units and condensate return units Source:[21] Energy saving is one of the key issues for both fossil fuel consumption and the protection of the global environment.

Moreover, cooling and dehumidifying fresh ventilation air compose 20–40% of the total energy load for HVAC in hot and humid climatic regions.

In this regard, stand-alone or combined heat recovery systems can be incorporated into residential or commercial buildings for energy saving.

To use proper ventilation; recovery is a cost-efficient, sustainable and quick way to reduce global energy consumption and give better indoor air quality (IAQ) and protect buildings, and environment.

Subsequently, this air cools the condenser coil at a lower temperature than if the rejected heat had not entered the exhaust airstream.

The coefficient of performance (COP) will increase as the conditions become more extreme (i.e., more hot and humid for cooling and colder for heating).

[25][obsolete source] The use of modern low-cost gas-phase heat exchanger technology will allow for significant improvements in efficiency.

Since the inside air is approximately 20–22 degrees Celsius all year round, the maximum output power of the heat pump is not varying with the seasons and outdoor temperature.

[citation needed] Air leaving the building when the heat pump's compressor is running is usually at around −1° in most versions.

[33] Many families are still battling with developers to have their EAHP systems replaced with more reliable and efficient heating, noting the success of residents in Coventry.