Heidelberg in the Roman period

Even after the garrison of the Heidelberg fort was withdrawn around the year 135, the civilian settlement continued to flourish thanks to its favorable geographical location and developed into a prosperous pottery center.

Nevertheless, Heidelberg always remained in the shadow of neighboring Lopodunum (today Ladenburg), which was the main city of the region at the time.

The location at the intersection of the Neckar and the Bergstraße running along the edge of the mountains is extremely favorable in terms of transport geography.

The 440-metre-high Heiligenberg, which rises opposite the old town on the edge of the Odenwald, has also attracted people for thousands of years due to its favorable sheltered location.

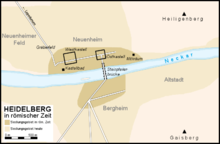

Heidelberg during the Roman period was located just under two kilometers west of the old town in the plain on the north shore of the Neckar in today's Neuenheim district.

According to the ancient authors Ptolemy and Tacitus, the Celtic inhabitants of southwestern Germany were members of the Helvetii tribe.

In the 1st century BC, the Helvetii gave up their ancestral homes under pressure from the advancing Germanic tribe of the Suebi under Ariovistus.

The area east of the Rhine, known as Agri decumates, remained largely uninhabited for almost a century and is described by Ptolemy as a "Helvetic wasteland".

[4] Settlements (vici) developed around the fort on both sides of the Neckar, which soon grew and prospered economically thanks to Heidelberg's favorable geographical location.

In response to an uprising by the provincial governor Lucius Antonius Saturninus in Mogontiacum, the Romans considered it necessary to further improve the traffic situation between the Rhine and the Danube.

For this reason, at the same time as the construction of the Neckar-Odenwald Limes, a new military road was probably built between Mogontiacum and Augusta Vindelicum (Augsburg) between 100 and 120.

In the east, the Romans were threatened by the Persian Sasanian Empire, on the Danube the Goths exerted pressure, and on the Rhine was an onslaught by the Alemanni.

Despite several campaigns against the Alamanni, the Roman emperors were unable to stabilize the situation, with the result that raids and pillaging became more frequent in Upper Germania over the next few decades.

At the same time as the usurpation of Postumus, who founded a special Gallic Empire in 260, there was a devastating invasion by the Alamanni, Franks, and Juthungi.

Evidence of the crisis can also be seen in the finds of a pottery and metal deposit in a Roman cellar as well as a coin hoard, which was buried at the west gate of the fort in the 1930s for fear of the Germanic tribes and was never dug up again.

[8] After the abandonment of the Limes, the Alamanni began to colonize the vacated land, as evidenced by grave finds from the 4th and 5th centuries in Heidelberg.

The oldest parts of Heidelberg date back to village foundations from the time of the Frankish colonisation in the 6th century, while the actual city was only founded in the Middle Ages at the foot of the castle and was first mentioned in 1196.

It was located roughly in the area of today's Posselt, Kastellweg, Gerhart-Hauptmann and Furchgasse streets and had an almost square shape with sides measuring 176 or 178 meters.

The Heidelberg Fort was laid out according to the typical pattern of Roman military camps: There was a gate on each of the four sides, where the moat was interrupted and protected by two massive stone towers.

The commander's residence (praetorium) and baths, a storage building (horreum) and presumably also the military hospital (valetudinarium) were built of stone.

[12] The discovery of the bone end reinforcement of a bow and arrow in the area of the eastern fort suggests that a unit of archers was temporarily stationed in Heidelberg.

The wood required for firing could be obtained in the Odenwald and floated through timber rafting down the Neckar, while the convenient location facilitated distribution.

[18] An unusual set of scales, whose originally gold-plated weighing pans were decorated with portraits of Emperor Domitian (reigned 81–96), bears witness to trading activities.

[21] However, it may also have been founded at the time of Emperor Nero (54–68), when the Romans had not yet permanently incorporated Heidelberg into their empire, but had already established strategic outposts on the right bank of the Rhine.

A beneficiarius station was located at the southern bridgehead, which the Legio VIII Augusta had set up to protect the bridge after the garrison withdrew from the Heidelberg fort around the year 150.

The cemetery is extremely well preserved, as its area was used for agriculture for a long time and remained untouched under the protective humus layer.

Depending on the financial circumstances of the deceased, the graves were marked by simple wooden plaques or imposed stone tombs.

It was located at a highly visible spot on the Roman highway south of Heidelberg and belonged to the cemetery of a nearby villa rustica.

Systematic archaeological investigations were carried out in Heidelberg from the middle of the 19th century under the direction of Karl Pfaff and were continued by Ernst Wahle after the First World War.

After the Second World War, Berndmark Heukemes devoted himself to researching Roman Heidelberg and was able to document the ancient remains before they were destroyed by the building boom of the 1950s and 60s.