Heinrich Böll

In 1942, Böll married Annemarie Cech, with whom he had three sons; she later collaborated with him on a number of different translations into German of English-language literature.

[7] He was given a number of honorary awards up to his death, such as the membership of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1974, and the Ossietzky Medal of 1974 (the latter for his defence of and contribution to global human rights).

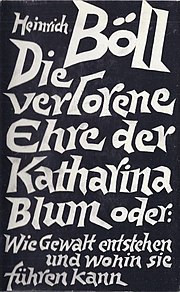

His best-known works are Billiards at Half-past Nine (1959), And Never Said a Word (1953), The Bread of Those Early Years (1955), The Clown (1963), Group Portrait with Lady (1971), The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1974), and The Safety Net (1979).

[12] In his autobiography, Böll wrote that at the high school he attended when growing up under Nazi rule, an anti-Nazi teacher paid special attention to the Roman satirist Juvenal: "Mr. Bauer realized how topical Juvenal was, how he dealt at length with such phenomena as arbitrary government, tyranny, corruption, the degradation of public morals, the decline of the Republican ideal and the terrorizing acts of the Praetorian Guards.

In particular, he was unable to forget the Concordat of July 1933 between the Vatican and the Nazis, signed by the future Pope Pius XII, which helped confer international legitimacy on the regime early in its development.

His 1972 article Soviel Liebe auf einmal (So much love at once), which accused the tabloid Bild of falsified journalism, was in turn retitled,[clarification needed] at the time of publishing and against Böll's wishes, by Der Spiegel, and the new title was used as a pretext to accuse Böll of sympathy with terrorism.

[17] This particular criticism was driven in large part by his repeated insistence on the importance of due process and the correct and fair application of the law in the case of the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

[12] The conservative press even attacked Böll's 1972 Nobel Prize, arguing that it was awarded only to "liberals and left-wing radicals".

[19] Böll was deeply rooted in his hometown of Cologne, with its strong Roman Catholicism and rather rough and drastic sense of humour.

(Böll seems to have been an admirer of William Morris; he let it be known that he would have preferred that Cologne Cathedral be left unfinished, with the 14th-century wooden crane at the top, as it had stood in 1848).

[citation needed] Böll had a great fondness for Ireland, holidaying with his wife at their second home there, on the west coast.

Böll's villains are the figures of authority in government, business, the mainstream media, and the Church, whom he castigates, sometimes humorously, sometimes acidly, for what he saw as their conformism, lack of courage, self-satisfied attitude, and abuse of power.

Newspapers in his books have no qualms about lying about the characters or destroying their lives, evoking Böll's experience of being accused of harboring and defending anarchists.

He was a leader of the German writers who tried to come to grips with the memory of World War II, the Nazis, the Holocaust, and the guilt that came with them.

This was a label Böll was keen to jettison, because he felt that it occluded a fair audit of the institutions truly responsible for what had happened.

The Irish connection also influenced the translations into German by his wife Annemarie, which included works by Brendan Behan, J. M. Synge, G. B. Shaw, Flann O'Brien, and Tomás Ó Criomhthain.

His appearance and attitude completely contrasted with the boastful, aggressive type of German who had become infamous during Adolf Hitler's rule.

Böll was particularly successful in Eastern Europe, as he seemed to portray the dark side of capitalism in his books, which sold by the millions in the Soviet Union alone.

The Cologne Library set up the Heinrich Böll Archive to house his personal papers, bought from his family, but much of the material was damaged, possibly irreparably, when the building collapsed in 2009.