Superfluid helium-4

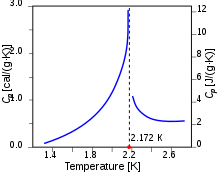

This condensation occurs in liquid helium-4 at a far higher temperature (2.17 K) than it does in helium-3 (2.5 mK) because each atom of helium-4 is a boson particle, by virtue of its zero spin.

In the 1950s, Hall and Vinen performed experiments establishing the existence of quantized vortex lines in superfluid helium.

[7] Packard has observed the intersection of vortex lines with the free surface of the fluid,[8] and Avenel and Varoquaux have studied the Josephson effect in superfluid helium-4.

[9] In 2006, a group at the University of Maryland visualized quantized vortices by using small tracer particles of solid hydrogen.

At the other limit, the fermions (most notably superconducting electrons) form Cooper pairs which also exhibit superfluidity.

This work with ultra-cold atomic gases has allowed scientists to study the region in between these two extremes, known as the BEC-BCS crossover.

[11][12] By quench cooling or lengthening the annealing time, thus increasing or decreasing the defect density respectively, it was shown, via torsional oscillator experiment, that the supersolid fraction could be made to range from 20% to completely non-existent.

Superfluids are also used in high-precision devices such as gyroscopes, which allow the measurement of some theoretically predicted gravitational effects (for an example, see Gravity Probe B).

This evaporation pulls energy from the overall system, which can be pumped out in a way completely analogous to normal refrigeration techniques.

So far the limit is 1.19 K, but there is a potential to reach 0.7 K.[17] Superfluids, such as helium-4 below the lambda point (known, for simplicity, as helium II), exhibit many unusual properties.

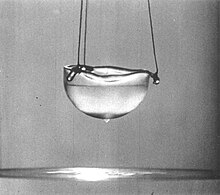

Many ordinary liquids, like alcohol or petroleum, creep up solid walls, driven by their surface tension.

It was, however, observed, that the flow through nanoporous membrane becomes restricted if the pore diameter is less than 0.7 nm (i.e. roughly three times the classical diameter of helium atom), suggesting the unusual hydrodynamic properties of He arise at larger scale than in the classical liquid helium.

That is, when the container is rotated at speeds below the first critical angular velocity, the liquid remains perfectly stationary.

If the rotation speed is increased more and more quantized vortices will be formed which arrange in nice patterns similar to the Abrikosov lattice in a superconductor.

On the other hand, helium-3 atoms are fermions, and the superfluid transition in this system is described by a generalization of the BCS theory of superconductivity.

In it, Cooper pairing takes place between atoms rather than electrons, and the attractive interaction between them is mediated by spin fluctuations rather than phonons.

A unified description of superconductivity and superfluidity is possible in terms of gauge symmetry breaking.

Thus we get the equation which states that the thermodynamics of a certain constant will be amplified by the force of the natural gravitational acceleration Eq.

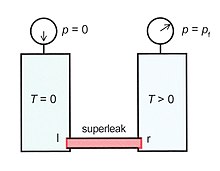

(1) shows that, in the case of the superfluid component, the force contains a term due to the gradient of the chemical potential.

So, in many experiments, the fountain pressure has a bigger effect on the motion of the superfluid helium than gravity.

The high thermal conductivity of He-II is applied for stabilizing superconducting magnets such as in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Landau also showed that the sound wave and other excitations could equilibrate with one another and flow separately from the rest of the helium-4, which is known as the "condensate".

The Landau theory does not elaborate on the microscopic structure of the superfluid component of liquid helium.

[31] The first attempts to create a microscopic theory of the superfluid component itself were done by London[32] and subsequently, Tisza.

Their main objective is to derive the form of the inter-particle potential between helium atoms in superfluid state from first principles of quantum mechanics.

Lars Onsager and, later independently, Feynman showed that vorticity enters by quantized vortex lines.

Arie Bijl in the 1940s,[35] and Richard Feynman around 1955,[36] developed microscopic theories for the roton, which was shortly observed with inelastic neutron experiments by Palevsky.

[37][38] The models are based on the simplified form of the inter-particle potential between helium-4 atoms in the superfluid phase.

The short-wavelength part describes the interior structure of the fluid element using a non-perturbative approach based on the logarithmic Schrödinger equation; it suggests the Gaussian-like behaviour of the element's interior density and interparticle interaction potential.

[42] The approach provides a unified description of the phonon, maxon and roton excitations, and has noteworthy agreement with experiment: with one essential parameter to fit one reproduces at high accuracy the Landau roton spectrum, sound velocity and structure factor of superfluid helium-4.