Saturation diving

A diver breathing pressurized gas accumulates dissolved inert gas used in the breathing mixture to dilute the oxygen to a non-toxic level in the tissues, which can cause potentially fatal decompression sickness ("the bends") if permitted to come out of solution within the body tissues; hence, returning to the surface safely requires lengthy decompression so that the inert gases can be eliminated via the lungs.

Once the dissolved gases in a diver's tissues reach the saturation point, however, decompression time does not increase with further exposure, as no more inert gas is accumulated.

On December 22, 1938, Edgar End and Max Nohl made the first intentional saturation dive by spending 27 hours breathing air at 101 feet sea water (fsw) (30.8 msw) in the County Emergency Hospital recompression facility in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

[5] Albert R. Behnke proposed the idea of exposing humans to increased ambient pressures long enough for the blood and tissues to become saturated with inert gases in 1942.

[6][7] In 1957, George F. Bond began the Genesis project at the Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory proving that humans could in fact withstand prolonged exposure to different breathing gases and increased environmental pressures.

[5] In the same year, the Conshelf III experiment was carried out by divers of Jacques Cousteau at the depth of 100 m.[10] Peter B. Bennett is credited with the invention of trimix breathing gas as a method to eliminate high pressure nervous syndrome.

The tables allowed decompression to start directly after return from a dive provided there had not been an upward excursion, as this was found to increase the risk of bubble development.

[12] At the same time, the commercial diving contractor Compagnie maritime d'expertises (COMEX) had been developing slightly different decompression procedures, in which the oxygen partial pressures were higher, between 0.6 and 0.8 bar, and the ascent rates were faster to take advantage of the high PO2.

[15] Saturation diving is standard practice for bottom work at many of the deeper offshore sites, and allows more effective use of the diver's time while reducing the risk of decompression sickness.

Decompression sickness (DCS) is a potentially fatal condition caused by bubbles of inert gas, which can occur in divers' bodies as a consequence of the pressure reduction as they ascend.

To prevent decompression sickness, divers have to limit their rate of ascent, to reduce the concentration of dissolved gases in their body sufficiently to avoid bubble formation and growth.

The pain may occur in the knees, shoulders, fingers, back, hips, neck or ribs, and may be sudden and intense in onset and may be accompanied by a feeling of roughness in the joints.

[20] Onset commonly occurs around 60 msw (meters of sea water), and symptoms are variable depending on depth, compression rate and personal susceptibility.

[20] Saturation diving (or more precisely, long term exposure to high pressure) is associated with aseptic bone necrosis, although it is not yet known if all divers are affected or only especially sensitive ones.

[22][23][24] A breathing gas mixture of oxygen, helium and hydrogen was developed for use at extreme depths to reduce the effects of high pressure on the central nervous system.

[11] In 1981, during an extreme depth test dive to 686 metres (2251 ft) they breathed the conventional mixture of oxygen and helium with difficulty and suffered trembling and memory lapses.

On 18 November 1992, Comex decided to stop the experiment at an equivalent of 675 meters of sea water (msw) (2215 fsw) because the divers were suffering from insomnia and fatigue.

[37] The hyperbaric atmosphere in the accommodation chambers and the bell are controlled to ensure that the risk of long term adverse effects on the divers is acceptably low.

Most saturation diving is done on heliox mixtures, with partial pressure of oxygen in accommodation areas kept around 0.40 to 0.48 bar, which is near the upper limit for long term exposure.

Nitrogen partial pressure starts at 0.79 bar from the initial air content before compression, but tends to decrease over time as the system loses gas to lock operation, and is topped up with helium.

The US Navy Heliox saturation decompression rates require a partial pressure of oxygen to be maintained at between 0.44 and 0.48 atm when possible, but not to exceed 23% by volume, to restrict the risk of fire.

[44] Saturation diving systems are a variation of pressure vessels for human occupancy, which are subject to rules for life support, operations, maintenance, and structural design.

[48] This part is generally made of multiple compartments, including living, sanitation, and rest facilities, each a separate unit, joined by short lengths of cylindrical trunking.

[citation needed] One or more of the external doors may be provided with a mating flange or collar to suit a portable or transportable chamber, which can be used to evacuate a diver under pressure.

While in the volume tank, the gas can be analysed to ensure that it is suitable for re-use, and that the oxygen fraction is correct and carbon dioxide has been removed to specification before it is delivered to the divers.

In the event of a fire, toxic gases may be released by burning materials, and the occupants will have to use the built-in breathing systems (BIBS) until the chamber gas has been flushed sufficiently.

The four main classes of problem that must be managed during a hyperbaric evacuation are thermal balance, motion sickness, dealing with metabolic waste products, and severely cramped and confined conditions.[57]: Ch.

[61][62][63] In the real working conditions of the offshore oil industry, in Campos Basin, Brazil, Brazilian saturation divers from the DSV Stena Marianos (later Mermaid Commander (2006)) performed a manifold installation for Petrobras at 316 metres (1,037 ft) depth in February 1990.

When a lift bag attachment failed, the equipment was carried by the bottom currents to 328 metres (1,076 ft) depth, and the Brazilian diver Adelson D'Araujo Santos Jr. made the recovery and installation.

There is a trade-off against other risks associated with living under high-pressure saturation conditions, and the financial cost is high due to the complex infrastructure and expensive equipment and consumables required.

DDC – Living chamber

DTC – Transfer chamber

PTC – Personnel transfer chamber (bell)

RC – Recompression chamber

SL – Supply lock

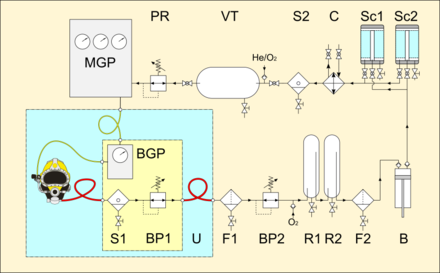

- BGP: bell gas panel

- S1: first water separator

- BP1: bell back-pressure regulator

- U: bell umbilical

- F1: first gas filter

- BP2: topside back-pressure regulator

- R1, R2: serial gas receivers

- F2: second gas filter

- B: booster pump

- Sc1, Sc2: parallel scrubbers

- C: gas cooler

- S2: last water separator

- VT: volume tank

- PR: pressure regulator

- MGP: main gas panel