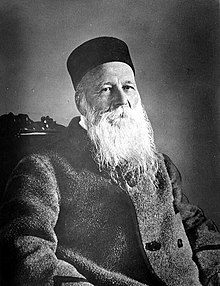

Henry Dunant

Horrified by the suffering of the wounded and the lack of care they received, Dunant took the initiative to organize the local population in providing aid for the soldiers.

After returning to Geneva, he recorded his experiences in the book A Memory of Solferino, in which he advocated the formation of an organization that would provide relief for the wounded without discrimination in times of war.

In 1895, Dunant was rediscovered by a journalist, which brought him renewed attention and support, and in 1901 he was awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize alongside French pacifist Frédéric Passy.

In the following year, together with friends, he founded the so-called "Thursday Association", a loose band of young men that met to study the Bible and help the poor, and he spent much of his free time engaged in prison visits and social work.

In 1849, at age 21, Dunant left the Collège de Genève due to poor grades and began an apprenticeship with the money-changing firm Lullin et Sautter.

As a result, in 1859 Dunant decided to appeal directly to French emperor Napoléon III, who was with his army in Lombardy at the time.

Dunant wrote a flattering book full of praise for Napoleon III with the intention to present it to the emperor and then travelled to Solferino to meet with him personally.

Shocked, Dunant himself took the initiative to organize the civilian population, especially the women and girls, to provide assistance to the injured and sick soldiers.

He convinced the population to service the wounded without regard to their side in the conflict as per the slogan "Tutti fratelli" (All are brothers) coined by the women of the nearby city Castiglione delle Stiviere.

The others were Moynier, the Swiss army general Henri Dufour, and doctors Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir.

Their first meeting on 17 February 1863 is now considered the founding date of the International Committee of the Red Cross.From early on, Moynier and Dunant had increasing disagreements and conflicts regarding their respective visions and plans.

In October 1863, 14 states took part in a meeting in Geneva organized by the committee to discuss improving care for wounded soldiers.

A year later, on 22 August 1864, a diplomatic conference organized by the Swiss government led to the signing of the First Geneva Convention by 12 states.

The social outcry in Geneva, a city deeply rooted in Calvinist traditions, also led to calls for him to separate himself from the International Committee.

In his continued pursuit and advocacy of his ideas, he further neglected his personal situation and income, falling further into debt and being shunned by his acquaintances.

In Heiden, he met the young teacher Wilhelm Sonderegger and his wife Susanna; they encouraged him to record his life experiences.

In September 1895, Georg Baumberger, the chief editor of the St. Gall newspaper Die Ostschweiz, wrote an article about the Red Cross founder, whom he had met and conversed with during a walk in Heiden a month earlier.

In 1897, Rudolf Müller, who was now working as a teacher in Stuttgart, wrote a book about the origins of the Red Cross, altering the official history to stress Dunant's role.

Dunant began an exchange of correspondence with Bertha von Suttner and wrote numerous articles and writings.

In 1901, Dunant was awarded the first-ever Nobel Peace Prize for his role in founding the International Red Cross Movement and initiating the Geneva Convention.

[4][5] The award was jointly given to French pacifist Frédéric Passy, founder of the Peace League and active with Dunant in the Alliance for Order and Civilization.

However, another part of Nobel's testament marked the prize for the individual who had best enhanced the "brotherhood of people," which could be interpreted more generally as seeing humanitarian work like Dunant's as connected to peacemaking as well.

Hans Daae succeeded in placing Dunant's part of the prize money, 104,000 Swiss Francs, in a Norwegian Bank and preventing access by his creditors.

There were even days when Dunant insisted that the cook of the nursing home first taste his food before his eyes to protect him against possible poisoning.

[6] According to his nurses, the final act of his life was to send a copy of Müller's book to the Italian queen with a personal dedication.

In his will, he donated funds to secure a "free bed" in the Heiden nursing home always to be available for a poor citizen of the region and deeded some money to friends and charitable organizations in Norway and Switzerland.