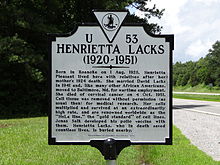

Henrietta Lacks

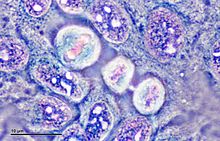

[8] Lacks was the unwitting source of these cells from a tumor biopsied during treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1951.

With knowledge of the cell line's genetic provenance becoming public, its use for medical research and for commercial purposes continues to raise concerns about privacy and patients' rights.

[11] She is remembered as having hazel eyes, a small waist, size 6 shoes, and always wearing red nail polish and a neatly pleated skirt.

She attended the designated black school two miles away from the cabin until she had to drop out to help support the family when she was in the sixth grade.

Now part of Dundalk, Turner Station was one of the oldest and largest African-American communities in Baltimore County at that time.

[19] Henrietta gave birth to her last child at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore in November 1950, four and a half months before she was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

[20] On January 29, 1951, Lacks went to Johns Hopkins, the only hospital in the area that treated black patients, because she felt a "knot" in her womb.

[27] Lacks was treated with radium tube inserts as an inpatient and discharged a few days later with instructions to return for X-ray treatments as a follow-up.

[2] On August 8, 1951, Lacks, who was 31 years old, went to Johns Hopkins for a routine treatment session and asked to be admitted due to continued severe abdominal pain.

[35] Until then, cells cultured for laboratory studies survived for only a few days at most, which was not long enough to perform a variety of different tests on the same sample.

After Lacks's death, Gey had Mary Kubicek, his lab assistant, take further HeLa samples while Henrietta's body was at Johns Hopkins' autopsy facility.

[2] The ability to rapidly reproduce HeLa cells in a laboratory setting has led to many important breakthroughs in biomedical research.

They were mailed to scientists around the globe for "research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, gene mapping, and countless other scientific pursuits".

[42][43] Alarmed and confused, several family members began questioning why they were receiving so many telephone calls requesting blood samples.

In 1975, the family also learned through a chance dinner-party conversation that material originating in Henrietta Lacks was continuing to be used for medical research.

That same year another group working on a different HeLa cell line's genome under National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, submitted it for publication.

Led by physician Roland Pattillo, the conference is held to give recognition to Henrietta Lacks, her cell line, and "the valuable contribution made by African Americans to medical research and clinical practice".

Congressman from Maryland, Robert Ehrlich, presented a congressional resolution recognizing Lacks and her contributions to medical science and research.

"Through her life and her immortal cells, Henrietta Lacks made an immeasurable impact on science and medicine that has touched countless lives around the world," Daniels said.

[74] Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist at the WHO, said: "I cannot think of any other single cell line or lab reagent that's been used to this extent and has resulted in so many advances.

"[74] On March 15, 2022, United States Rep. Kwesi Mfume (D-Md) filed legislation to posthumously award the Congressional Gold Medal to Henrietta Lacks for her distinguished contributions to science.

[78][79] The question of how and whether her race affected her treatment, the lack of obtaining consent, and her relative obscurity continues to be controversial.

[92][93] NBC's Law & Order aired its own fictionalized version of Lacks's story in the 2010 episode "Immortal", which Slate referred to as "shockingly close to the true story"[94] and the musical groups Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine and Yeasayer both released songs about Henrietta Lacks and her legacy.

[97] The HeLa Project, a multimedia exhibition to honor Lacks, opened in 2017 in Baltimore at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture.

[98] HeLa, a play by Chicago playwright J. Nicole Brooks, was commissioned by Sideshow Theatre Company in 2016, with a public staged reading on July 31, 2017.

The play uses Lacks's life story as a jumping point for a larger conversation about Afrofuturism, scientific progress, and bodily autonomy.

[99] In the series El Ministerio del Tiempo, the immortality of her cells in the lab is cited as the precedent for the character Arteche's "extreme resistance to infections, to injuries, and to cellular degeneration.

[100] In the Netflix original movie Project Power (2020), the case of Henrietta Lacks is cited by one of the villains of the story as an example of unwilling trials giving rise to advances for the greater good.

[101] The JJ Doom album Key to the Kuffs (2012) includes the song "Winter Blues" that contains the lyrics "We could live forever like Henrietta Lacks cells".

[103] In 2020, playwright Sandra Seaton wrote a one-woman piece titled Call Me By My Name, focusing on Henrietta Lacks.