Henry David Thoreau

His literary style interweaves close observation of nature, personal experience, pointed rhetoric, symbolic meanings, and historical lore, while displaying a poetic sensibility, philosophical austerity, and attention to practical detail.

[4] He was also deeply interested in the idea of survival in the face of hostile elements, historical change, and natural decay; at the same time he advocated abandoning waste and illusion in order to discover life's true essential needs.

The traditional professions open to college graduates—law, the church, business, medicine—did not interest Thoreau,[35]: 25 so in 1835 he took a leave of absence from Harvard, during which he taught at a school in Canton, Massachusetts, living for two years at an earlier version of today's Colonial Inn in Concord.

Emerson urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly periodical, The Dial, and lobbied the editor, Margaret Fuller, to publish those writings.

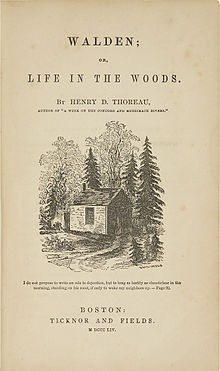

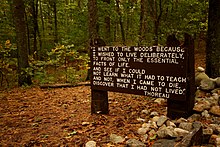

[58] At Walden Pond, Thoreau completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother John, describing their trip to the White Mountains in 1839.

[64] In fact, this proved an opportunity to contrast American civic spirit and democratic values with a colony apparently ruled by illegitimate religious and military power.

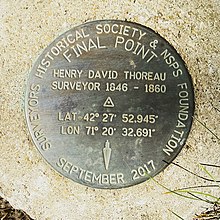

He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated.

With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism as academic disciplines, several new readings of Thoreau began to emerge, showing him to have been both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots.

Other travels took him southwest to Philadelphia and New York City in 1854 and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, when he visited Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Mackinac Island.

[72] Astonishing amounts of reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals.

He was a highly skilled canoeist; Nathaniel Hawthorne, after a ride with him, noted that "Mr. Thoreau managed the boat so perfectly, either with two paddles or with one, that it seemed instinct with his own will, and to require no physical effort to guide it.

He wrote in Walden, "The practical objection to animal food in my case was its uncleanness; and besides, when I had caught and cleaned and cooked and eaten my fish, they seemed not to have fed me essentially.

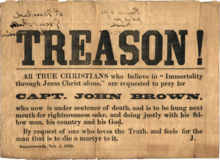

[1] He participated as a conductor in the Underground Railroad, delivered lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law, and in opposition to the popular opinion of the time, supported radical abolitionist militia leader John Brown and his party.

Despotic authority, Thoreau argued, had crushed the people's sense of ingenuity and enterprise; the Canadian habitants had been reduced, in his view, to a perpetual childlike state.

[105] Likewise, his condemnation of the Mexican–American War did not stem from pacifism, but rather because he considered Mexico "unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army" as a means to expand the slave territory.

On one hand he regarded commerce as "unexpectedly confident and serene, adventurous, and unwearied"[4] and expressed admiration for its associated cosmopolitanism, writing: I am refreshed and expanded when the freight train rattles past me, and I smell the stores which go dispensing their odors all the way from Long Wharf to Lake Champlain, reminding me of foreign parts, of coral reefs, and Indian oceans, and tropical climes, and the extent of the globe.

The condition of the operatives is becoming every day more like that of the English; and it cannot be wondered at, since, as far as I have heard or observed, the principal object is, not that mankind may be well and honestly clad, but, unquestionably, that the corporations may be enriched.

[4]Thoreau also favored the protection of animals and wild areas, free trade, and taxation for schools and highways,[1] and espoused views that at least in part align with what is today known as bioregionalism.

there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug.

Today, Thoreau's words are quoted with feeling by liberals, socialists, anarchists, libertarians, and conservatives alike.Thoreau's political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical", viewing him instead as a naturalist.

The only two complete books (as opposed to essays) that were published in his lifetime, Walden and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), both dealt with Nature, in which he "loved to wander".

Political leaders and reformers like Mohandas Gandhi, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and Russian author Leo Tolstoy all spoke of being strongly affected by Thoreau's work, particularly "Civil Disobedience", as did "right-wing theorist Frank Chodorov [who] devoted an entire issue of his monthly, Analysis, to an appreciation of Thoreau".

Gandhi first read "Civil Disobedience" while he sat in a South African prison for the crime of nonviolently protesting discrimination against the Indian population in the Transvaal.

He wrote in his autobiography that it was, Here, in this courageous New Englander's refusal to pay his taxes and his choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery's territory into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance.

Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters; a freedom ride into Mississippi; a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia; a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama; these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.

John Zerzan included Thoreau's text "Excursions" (1863) in his edited compilation of works in the anarcho-primitivist tradition titled Against civilization: Readings and reflections.

[146] Lowell's essay, Letters to Various Persons,[147] which he republished as a chapter in his book, My Study Windows,[148] derided Thoreau as a humorless poseur trafficking in commonplaces, a sentimentalist lacking in imagination, a "Diogenes in his barrel", resentfully criticizing what he could not attain.

[149] Lowell's caustic analysis influenced Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson,[149] who criticized Thoreau as a "skulker", saying "He did not wish virtue to go out of him among his fellow-men, but slunk into a corner to hoard it for himself.

He noted that "He is a keen and delicate observer of nature—a genuine observer—which, I suspect, is almost as rare a character as even an original poet; and Nature, in return for his love, seems to adopt him as her especial child, and shows him secrets which few others are allowed to witness.

[152][153] In a similar vein, poet John Greenleaf Whittier detested what he deemed to be the "wicked" and "heathenish" message of Walden, claiming that Thoreau wanted man to "lower himself to the level of a woodchuck and walk on four legs".