Henry Highland Garnet

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an American abolitionist, minister, educator, orator, and diplomat.

Renowned for his skills as a public speaker, he urged black Americans to take action and claim their own destinies.

After the war, the couple worked in Washington, D.C.[citation needed] On Sunday, February 12, 1865, he delivered a sermon in the U.S. House of Representatives while it was not in session, becoming the first African American to speak in that chamber,[3][4] on the occasion of Congress's passage on January 31 of the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery.

[5][6] "[H]is grandfather was an African chief and warrior, and in a tribal fight he was captured and sold to slave-traders who brought him to this continent where he was owned by Colonel William Spencer.

"[7] According to James McCune Smith, Garnet's father was George Trusty and his enslaved mother was "a woman of extraordinary energy.

"[8]: 18 In 1824, the family, which included a total of 11 members, secured permission to attend a funeral, and from there they all escaped in a covered wagon, via Wilmington, Delaware, where they were helped by the Quaker and Underground Railroad stationmaster Thomas Garrett.

His education there was interrupted in 1828 when Garnet had to find employment, twice making the sea route to Cuba as a cabin boy[8]: 23 and once as a cook and steward on a schooner running between New York City and Alexandria, Virginia.

Garnet, likely with his mother in mind, who had escaped by running to a corner store, took a knife and walked onto Broadway, waiting to be found and confronted by the slave catchers.

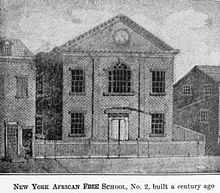

His classmates at the African Free School included Charles L. Reason, George T. Downing, and Ira Aldridge.

[citation needed] In 1835, Garnet enrolled at the new Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire, but anti-abolitionists soon destroyed the school building and forced the Negro students out of town.

Closely identifying with the church, Garnet supported the temperance movement and became a strong advocate of abolishing slavery.

[10] In 1848 Garnet relocated from Troy to Peterboro, New York, home of the great abolition activist Gerrit Smith.

"[13] On August 17, 1843, at the 1843 National Convention of Colored Citizens in Buffalo, New York, Garnet proposed that the meeting issue an address directly to enslaved people in the south, encouraging them that it would be better to rise up against their oppressors than to accept bondage.

Though controversial and never adopted by the meeting, the address marked what historian Stanley Harrold called the rise of a new more "aggressive" form of abolitionism.

Other prominent members of this movement included minister Daniel Payne, J. Sella Martin, Rufus L. Perry, Henry M. Wilson, and Amos Noë Freeman.

His wife Julia, his young son Henry, and their adopted daughter Stella Weims joined Garnet in Great Britain later that year.

Garnet and his family escaped attack because his daughter quickly chopped their nameplate off their door before the mobs found them.

[21] He organized a committee for sick soldiers and served as almoner to the New York Benevolent Society for victims of the mob.

During this time, Garnet was the first Black minister to preach to the US House of Representatives, addressing them on February 12, 1865, about the end of slavery, on occasion of the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

[24] In 1878, while living at 102 West 3rd Street,[25] in a neighborhood often referred to as Little Africa, Garnet hosted a reception for Cuban revolutionary leader Antonio Maceo.

[27] In 1875, Garnet married Sarah Smith Tompkins,[28][full citation needed] who was a New York teacher and school principal, suffragist, and community organizer.