Henry Hudson

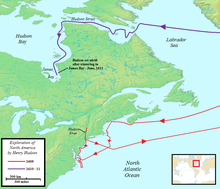

In 1607 and 1608, Hudson made two attempts on behalf of English merchants to find a rumoured Northeast Passage to Cathay via a route above the Arctic Circle.

In 1609, he landed in North America on behalf of the Dutch East India Company and explored the region around the modern New York metropolitan area.

Looking for a Northwest Passage to Asia[3] on his ship Halve Maen ("Half Moon"),[4] he sailed up the Hudson River, which was later named after him, and thereby laid the foundation for Dutch colonization of the region.

His voyages helped to establish European contact with the native peoples of North America and contributed to the development of trade and commerce.

[7][12] When Hudson first entered the historical record in 1607, he was already an experienced mariner with sufficient credentials to be commissioned the leader of an expedition charged with a search for a trade route across the North Pole.

It was thought that, because the sun shone for three months in the northern latitudes in the summer, the ice would melt, and a ship could make it across the "top of the world".

On 16 July, they reached as far north as Hakluyt's Headland (which Thomas Edge says Hudson named on this voyage) at 79° 49′ N, thinking they saw the land continue to 82° N (Svalbard's northernmost point is 80° 49′ N) when really it trended to the east.

Leaving London on 22 April, the ship travelled almost 2,500 mi (4,000 km), making it to Novaya Zemlya well above the Arctic Circle in July, but even in the summer they found the ice impenetrable and turned back, arriving at Gravesend on 26 August.

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the Dutch East India Company in the Netherlands to find an easterly passage to Asia.

He could not complete the specified (eastward) route because ice blocked the passage, as with all previous such voyages, and he turned the ship around in mid-May while somewhere east of Norway's North Cape.

The Pricket journal reports that the mutineers provided the castaways with clothing, powder and shot, some pikes, an iron pot, some food, and other miscellaneous items.

Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the Discovery, enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind.

Firstly, prior to the mutiny the alleged leaders of the uprising, Greene and Juet, had been friends and loyal seamen of Hudson.

One theory holds that the survivors were considered too valuable as sources of information to execute, as they had travelled to the New World and could describe sailing routes and conditions.

[37] British-born Canadian author Dorothy Harley Eber (1925–2022) collected Inuit testimonies that she thought made reference to Hudson and his son after the mutiny.

Charles Francis Hall, who searched for Franklin in the mid-19th century, also collected Inuit stories that he interpreted as references to the even earlier expedition of Martin Frobisher, who explored the area and mined fool's gold in 1578.

[38] In the late 1950s, a 150-pound (68 kg) stone near Deep River, Ontario, which is approximately 600 kilometres (370 mi) south of James Bay, was found to have carving on it with Hudson's initials (H. H.), the year 1612, and the word "captive".

[39] While lettering on the stone was consistent with English maps of the 17th century, the Geological Survey of Canada was unable to determine when the carving was made.

[37] The bay visited by and named after Hudson is three times the size of the Baltic Sea, and its many large estuaries afford access to otherwise landlocked parts of Western Canada and the Arctic.

This allowed the Hudson's Bay Company to exploit a lucrative fur trade along its shores for more than two centuries, growing powerful enough to influence the history and present international boundaries of western North America.