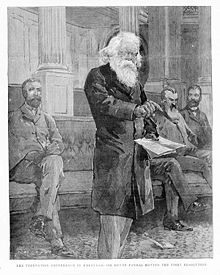

Henry Parkes

Alfred Deakin described Sir Henry Parkes as having flaws but nonetheless being "a large-brained self-educated Titan whose natural field was found in Parliament".

[5] After the loss of their two children at an early age and a few unsuccessful weeks living in London, Parkes and his wife emigrated to New South Wales.

After spending six months at Regentville, he returned to Sydney and worked in various low-paying jobs, first with an ironmongery store and then with a firm of engineers and brass-founders.

[2] About a year after his arrival in Sydney, Parkes was hired by the New South Wales Customs Department as a tide waiter, and given the task of inspecting merchant vessels to guard against smuggling.

[citation needed] Parkes' financial position improved due to his stable new government job, even though he was still burdened with a backlog of undischarged debts.

He met the poet Charles Harpur and William Augustine Duncan, the editor of a local newspaper; he mentions in his Fifty Years of Australian History, that these two men became his "chief advisers in matters of intellectual resource".

[5] In early 1846, he left the Customs Department after a disagreement with Colonel Gibbes over a press leak that concerned the alleged behaviour of one of Parkes' co-workers.

Some years later, Parkes said that, "in the heated opposition to the objectionable parts of Mr Wentworth's scheme, no sufficient attention was given to its great merits".

Parkes in his election speeches had advocated the extension of the power of the people, increased facilities for education and a bold railway policy.

He was persuaded to alter his mind, and a month later he stood as a liberal candidate for Sydney City in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly.

An investigation of Parkes' accounts found he had generally acted under the advice of his banker, and he was ultimately exonerated by the chief commissioner in insolvency of any fraudulent intent.

Relieved of his heavy work on the Empire, which was continued in other hands, Parkes stood for parliament and was elected for East Sydney on 10 June 1854.

Parkes also believed in immigration, and his well-known powers as an orator led to his being sent to England with William Dalley as commissioners of emigration at a salary of £1000 a year each in May 1861.

An important piece of legislation carried through was the Public Schools Act 1866, introduced by Parkes, which required teachers to have training and created a funding mechanism.

For a while his claims of a vast Fenian conspiracy in New South Wales gained some traction, but when nothing further occurred public opinion began to reverse and he was accused of being anti-Irish.

His ongoing financial woes had become a matter of some public notoriety, causing the barrister and fellow politician, William Dalley, to remark of Parkes, in 1872, that, "If he lives long, he will rule not over a nation of admirers and friends, but of creditors".

The Martin-Robertson ministry had involved itself in a dispute with the colony of Victoria over a question of border duties, and Parkes effectively threw ridicule on the proceedings.

When the announcement of his appointment was made on 11 November 1873, Butler took the opportunity to make a statement, read publicly the correspondence between Parkes and himself, and resigned his seat in the cabinet.

Two or three unsuccessful attempts were made to oust the government without success, but in February 1875, Governor Robinson's decision to release of the bushranger Frank Gardiner led to the defeat of the ministry.

It amended the electoral law, brought in a new education act, improved the water-supply and sewerage systems, appointed stipendiary magistrates, and regulated the liability of employers with regard to injuries to workers.

When he took his seat in September objection was taken to claims of parliamentary corruption he had made when resigning from Parliament in 1884, and Sir Alexander Stuart moved a resolution affirming that the words he had used were a gross libel on the house.

He proposed to do away with the recent increase in duties, to bring in an amended land act, and to create a body to control the railways free of political influence.

It is because I believe the Chinese to be a powerful race capable of taking a great hold upon the country, and because I want to preserve the type of my own nation .

[12] At the ensuing election Parkes was returned with a small majority and formed his fifth administration, which began in March 1889 and lasted until October 1891.

In October 1889 a report on the defences of Australia suggested among other things the federation of the forces of all the Australian colonies and a uniform gauge for railways.

In May he moved resolutions in the assembly approving of the proceedings of the conference that had just been held in Melbourne, and appointing him and three other members' delegates to the Sydney 1891 National Australasian Convention.

In response to pressure from Parkes, Reid endorsed a scheme of a second, directly elected federal convention, followed by a referendum.

Alfred Deakin described him as "though not rich or versatile, his personality was massive, durable and imposing, resting upon elementary qualities of human nature elevated by a strong mind.

He was cast in the mould of a great man and though he suffered from numerous pettinesses, spites and failings, he was in himself a large-brained self-educated Titan whose natural field was found in Parliament and whose resources of character and intellect enabled him in his later years to overshadow all his contemporaries".

They had five children, three born before their marriage: Parkes married thirdly in Parramatta on 23 October 1895 to Julia Lynch,[33] his 23-year-old former cook and housekeeper.