Heptatonic scale

Examples include: Indian classical theory postulates seventy-two seven-tone scale types, collectively called melakarta or thaat, whereas others postulate twelve or ten (depending on the theorist) seven-tone scale types.

Several heptatonic scales in Western, Roman, Spanish, Hungarian, and Greek music can be analyzed as juxtapositions of tetrachords.

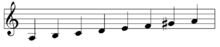

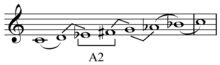

Thus starting on keynote A as above and following the notes of the ascending melodic minor (A, B, C, D, E, F♯, G♯) yields these seven modes: These modes are more awkward to use than those of the diatonic scales due to the four tones in a row yielding augmented intervals on one hand while the one tone between two semitones gives rise to diminished intervals on the other.

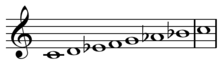

Verdi's Scala Enigmatica I-♭II-III-♯IV-♯V-♯VI-VII i.e. G A♭ B C♯ D♯ E♯ F♯, which is similar to the heptatonia tertia mentioned above, differing only in that the second degree here is flattened.

Melakarta is a South Indian classical method of organizing Raagas based on their unique heptatonic scales.

The postulated number of melakarta derives from arithmetical calculation and not from Carnatic practice, which uses far fewer scale forms.

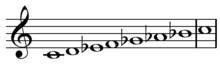

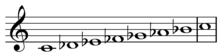

Thus the number of possible forms is equal to twice the square of the number of ways a two-membered subset can be extracted from a four-membered set: Hindustani heptatonic theory additionally stipulates that the second, third, sixth and seventh degrees of heptatonic scale forms (saptak) are also allowed only two inflections each, in this case, one natural position, and one lowered (komal) position.