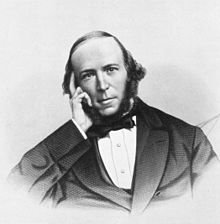

Herbert Spencer

As a polymath, he contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, literature, astronomy, biology, sociology, and psychology.

Spencer was educated in empirical science by his father, while the members of the Derby Philosophical Society introduced him to pre-Darwinian concepts of biological evolution, particularly those of Erasmus Darwin and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

However, it was the friendship of Evans and Lewes that acquainted him with John Stuart Mill's A System of Logic and with Auguste Comte's positivism and which set him on the road to his life's work.

[10] Spencer argued that both these theories are partial accounts of the truth: repeated associations of ideas are embodied in the formation of specific strands of brain tissue, and these can be passed from one generation to the next by means of the Lamarckian mechanism of use-inheritance.

However, Spencer differed from Comte in believing it is possible to discover a single law of universal application which he identified with progressive development and was to call the principle of evolution.

This immense undertaking, which has few parallels in the English language, aimed to demonstrate that the principle of evolution applies in biology, psychology, sociology (Spencer appropriated Comte's term for the new discipline) and morality.

[13] His works were widely read during his lifetime, and by 1869 he was able to support himself solely on the profit of book sales and on income from his regular contributions to Victorian periodicals which were collected as three volumes of Essays.

His works were translated into German, Italian, Spanish, French, Russian, Japanese and Chinese, and into many other languages and he was offered honours and awards all over Europe and North America.

[20] The basis for Spencer's appeal to many of his generation was that he appeared to offer a ready-made system of belief which could substitute for conventional religious faith at a time when orthodox creeds were crumbling under the advances of modern science.

[21] Spencer's philosophical system seemed to demonstrate that it is possible to believe in the ultimate perfection of humanity on the basis of advanced scientific conceptions such as the first law of thermodynamics and biological evolution.

On the one hand, he had imbibed something of eighteenth-century deism from his father and other members of the Derby Philosophical Society and from books like George Combe's immensely popular The Constitution of Man (1828).

Even in his writings on ethics, he held that it is possible to discover 'laws' of morality that have the status of laws of nature while still having normative content, a conception which can be traced to George Combe's Constitution of Man.

Bertrand Russell stated in a letter to Beatrice Webb in 1923: 'I don't know whether [Spencer] was ever made to realize the implications of the second law of thermodynamics; if so, he may well be upset.

The primary mechanism of species transformation that he recognised was Lamarckian use-inheritance which posited that organs are developed or are diminished by use or disuse and that the resulting changes may be transmitted to future generations.

Spencer in his book Principles of Biology (1864), proposed a pangenesis theory that involves "physiological units" assumed to be related to specific body parts and responsible for the transmission of characteristics to offspring.

In the United States, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward, who would be elected as the first president of the American Sociological Association, launched a relentless attack on Spencer's theories of laissez-faire and political ethics.

Because human instincts have a specific location in strands of brain tissue, they are subject to the Lamarckian mechanism of use-inheritance so that gradual modifications could be transmitted to future generations.

Hence anything that interferes with the 'natural' relationship of conduct and consequence was to be resisted and this included the use of the coercive power of the state to relieve poverty, to provide public education, or to require compulsory vaccination.

Hence too much individual benevolence directed to the 'undeserving poor' would break the link between conduct and consequence that Spencer considered fundamental to ensuring that humanity continues to evolve to a higher level of development.

Speakers have persuasive effect not only by the reasoning of their words, but by their cadence and tone – the musical qualities of their voice serve as "the commentary of the emotions upon the propositions of the intellect," as Spencer put it.

Nonetheless, unlike Thomas Henry Huxley, whose agnosticism was a militant creed directed at 'the unpardonable sin of faith' (in Adrian Desmond's phrase), Spencer insisted that he was not concerned with undermining religion in the name of science, but to bring about a reconciliation of the two.

"[32] Politics in late Victorian Britain moved in directions that Spencer disliked, and his arguments provided so much ammunition for conservatives and individualists in Europe and America that they are still in use in the 21st century.

[35] While often caricatured as ultra-conservative, Spencer had been more radical, or left-libertarian,[36] earlier in his career, opposing private property in land and claiming that each person has a latent claim to participate in the use of the earth (views that influenced Georgism),[37] calling himself "a radical feminist" and advocating the organisation of trade unions as a bulwark against "exploitation by bosses", and favoured an economy organised primarily in free worker co-operatives as a replacement for wage-labor.

Spencer viewed private charity positively, encouraging both voluntary association and informal care to aid those in need, rather than relying on government bureaucracy or force.

As William James remarked, Spencer "enlarged the imagination, and set free the speculative mind of countless doctors, engineers, and lawyers, of many physicists and chemists, and of thoughtful laymen generally.

Half a century after his death, his work was dismissed as a "parody of philosophy",[49] and the historian Richard Hofstadter called him "the metaphysician of the homemade intellectual, and the prophet of the cracker-barrel agnostic.

[58] Savarkar writes, in his Inside the Enemy Camp, about reading all of Spencer's works, of his great interest in them, of their translation into Marathi, and their influence on the likes of Tilak and Agarkar, and the affectionate sobriquet given to him in Maharashtra – Harbhat Pendse.

Spencer aimed to free prose writing from as much "friction and inertia" as possible, so that the reader would not be slowed by strenuous deliberations concerning the proper context and meaning of a sentence.

In Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim, the Anglophile Bengali spy Hurree Babu admires Herbert Spencer and quotes him to comic effect: "They are, of course, dematerialised phenomena.

Upton Sinclair, in One Clear Call, 1948, quips that "Huxley said that Herbert Spencer's idea of a tragedy was a generalization killed by a fact; ..."[60] Essay Collections: Biographical Sources