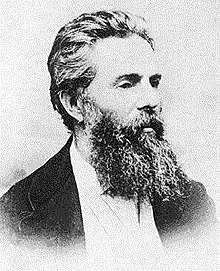

Herman Melville

His seven siblings, who played important roles in his career and emotional life,[4] were Gansevoort, Helen Maria, Augusta, Allan, Catherine, Frances Priscilla, and Thomas, who eventually became a governor of Sailors' Snug Harbor.

Part of a well-established and colorful Boston family, Allan Melvill spent considerable time away from New York City, travelling regularly to Europe as a commission merchant and an importer of French dry goods.

[19] "Herman I think is making more progress than formerly," Allan wrote in May 1830 to Major Melvill, "and without being a bright Scholar, he maintains a respectable standing, and would proceed further, if he could only be induced to study more—being a most amiable and innocent child, I cannot find it in my heart to coerce him".

[24] In early August 1831, Herman marched in the Albany city government procession of the year's "finest scholars" and was presented with a copy of The London Carcanet, a collection of poems and prose, inscribed to him as "first best in ciphering books".

[50] According to Merton Sealts, his use of heavy-handed allusions reveals familiarity with the work of William Shakespeare, John Milton, Walter Scott, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Edmund Burke, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, and Thomas Moore.

On Sunday the 27th, the brothers heard Reverend Enoch Mudge preach at the Seamen's Bethel on Johnnycake Hill, where white marble cenotaphs on the walls memorialized local sailors who had died at sea, often in battle with whales.

[72] By around mid-August, Melville had left the island aboard the Australian whaler Lucy Ann, bound for Tahiti, where he took part in a mutiny and was briefly jailed in the native Calabooza Beretanee.

[71] During the next year, the homeward bound ship visited the Marquesas Islands, Tahiti, and Valparaiso, and then, from summer to fall 1844, Mazatlan, Lima, and Rio de Janeiro,[54] before reaching Boston on October 3.

[76] Milder calls Typee "an appealing mixture of adventure, anecdote, ethnography, and social criticism presented with a genial latitudinarianism that gave novelty to a South Sea idyll at once erotically suggestive and romantically chaste".

An unsigned review in the Salem Advertiser written by Nathaniel Hawthorne called the book a "skilfully managed" narrative by an author with "that freedom of view ... which renders him tolerant of codes of morals that may be little in accordance with our own".

The gentleness of disposition that seems akin to the delicious climate, is shown in contrast with the traits of savage fierceness...He has that freedom of view—it would be too harsh to call it laxity of principle—which renders him tolerant of codes of morals that may be little in accordance with our own, a spirit proper enough to a young and adventurous sailor, and which makes his book the more wholesome to our staid landsmen.

[92] According to Milder, the book began as another South Sea story but, as he wrote, Melville left that genre behind, first in favor of "a romance of the narrator Taji and the lost maiden Yillah," and then "to an allegorical voyage of the philosopher Babbalanja and his companions through the imaginary archipelago of Mardi".

[98] From August 4 to 12, 1850, the Melvilles, Sarah Morewood, Duyckinck, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and other literary figures from New York City and Boston came to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to enjoy a period of parties, picnics, and dinners.

The critic Walter Bezanson finds the essay "so deeply related to Melville's imaginative and intellectual world while writing Moby-Dick" that it could be regarded as a virtual preface and should be "everybody's prime piece of contextual reading".

[103] Hawthorne read them, as he wrote to Duyckinck on August 29 that Melville in Redburn and White-Jacket put the reality "more unflinchingly" before his reader than any writer, and he thought Mardi was "a rich book, with depths here and there that compel a man to swim for his life".

The item, offered as a news story, reported, A critical friend, who read Melville's last book, Ambiguities, between two steamboat accidents, told us that it appeared to be composed of the ravings and reveries of a madman.

[134]) During these years, Melville suffered from nervous exhaustion, physical pain, and frustration, and would sometimes, in the words of Robertson-Lorant, behave like the "tyrannical captains he had portrayed in his novels", perhaps even beating his wife Lizzie when he came home after drinking.

Such compact organization bears the risk of fragmentation when applied to a lengthy work such as Mardi, but with Redburn and White Jacket, Melville turned the short chapter into a concentrated narrative.

The skillful handling of chapters in Moby-Dick is one of the most fully developed Melvillean signatures, and is a measure of his masterly writing style (something that would lend lasting significance to the opening lines "Call me Ishmael").

In reality, his movement "was not a retrograde but a spiral one", and while Redburn and White Jacket may lack the spontaneous, youthful charm of his first two books, they are "denser in substance, richer in feeling, tauter, more complex, more connotative in texture and imagery".

Instead of providing a lead "into possible meanings and openings-out of the material in hand,"[158] the vocabulary now served "to crystallize governing impressions,"[158] the diction no longer attracted attention to itself, except as an effort at exact definition.

Redburn's "Thou shalt not lay stripes upon these Roman citizens" makes use of language of the Ten Commandments in Ex.20 and Pierre's inquiry of Lucy: "Loveth she me with the love past all understanding?"

This passage from Redburn shows how these ways of alluding interlock and result in a texture of Biblical language though there is very little direct quotation: The other world beyond this, which was longed for by the devout before Columbus' time, was found in the New; and the deep-sea land, that first struck these soundings, brought up the soil of Earth's Paradise.

119) makes the last clause lead to a "compulsion to strike the breast," which suggests "how thoroughly the drama has come to inhere in the words;"[180] Second, Melville took advantage of the Shakespearean energy of verbal compounds, as in "full-freighted".

[196] The postwar scholars tended to think that Weaver, Harvard psychologist Henry Murray, and Mumford favored Freudian interpretations that read Melville's fiction as autobiography; exaggerated his suffering in the family; and inferred a homosexual attachment to Hawthorne.

[197] Other post-war studies, however, continued the broad imaginative and interpretive style; Charles Olson's Call Me Ishmael (1947) presented Ahab as a Shakespearean tragic hero, and Newton Arvin's critical biography, Herman Melville (1950), won the National Book Award for non-fiction in 1951.

[197][198] In the 1960s, Harrison Hayford organized an alliance between Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, with backing from the Modern Language Association and funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, to edit and publish reliable critical texts of Melville's complete works, including unpublished poems, journals, and correspondence.

Alvin Sandberg said that the short story "The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids" offers "an exploration of impotency, a portrayal of a man retreating to an all-male childhood to avoid confrontation with sexual manhood," from which the narrator engages in "congenial" digressions in heterogeneity.

As early as 1839, in the juvenile sketch "Fragments from a Writing Desk", Melville explores a problem that would reappear in the short stories "Bartleby" (1853) and "Benito Cereno" (1855): the impossibility to find common ground for mutual communication.

The sketch centers on the protagonist and a mute lady, leading scholar Sealts to observe: "Melville's deep concern with expression and communication evidently began early in his career".