Hermeticism

[a] This system encompasses a wide range of esoteric knowledge, including aspects of alchemy, astrology, and theurgy, and has significantly influenced various mystical and occult traditions throughout history.

The broader term, Hermeticism, may refer to a wide variety of philosophical systems drawing on Hermetic writings or other subject matter associated with Hermes.

[3] This idea, popular among Renaissance thinkers like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), eventually developed into the notion that divine truth could be found across different religious and philosophical traditions, a concept that came to be known as the perennial philosophy.

[4] In this context, the term 'Hermetic' gradually lost its specificity, eventually becoming synonymous with the divine knowledge of the ancient Egyptians, particularly as related to alchemy and magic, a view that was later popularized by nineteenth- and twentieth-century occultists.

Hermes Trismegistus was revered as a divine sage and is credited with a vast corpus of writings known as the Hermetica, which expound on various aspects of theology, cosmology, and spiritual practice.

[6] Hermetism developed alongside other significant religious and philosophical movements such as early Christianity, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, the Chaldean Oracles, and late Orphic and Pythagorean literature.

"[7] Plutarch's mention of Hermes Trismegistus dates back to the first century CE, indicating the early recognition of this figure in Greek and Roman thought.

The Hermetic idea of a transcendent, ineffable God who created the cosmos through a process of emanation resonated with early Christian theologians, who sought to reconcile their faith with classical philosophy.

Both movements taught that the soul’s true home was in the divine realm and that the material world was a place of exile, albeit with a more positive view in Hermeticism.

These treatises are primarily dialogues in which Hermes Trismegistus imparts esoteric wisdom to a disciple, exploring themes such as the nature of the divine, the cosmos, the soul, and the path to spiritual enlightenment.

Key texts within the Corpus Hermeticum include Poimandres, which presents a vision of the cosmos and the role of humanity within it, and Asclepius, which discusses theurgy, magic, and the divine spirit residing in all things.

The translations by Marsilio Ficino and Lodovico Lazzarelli were particularly significant, as they introduced Hermetic ideas to Renaissance scholars and contributed to the development of early modern esotericism.

[14] Renaissance thinkers like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Giordano Bruno saw in Hermeticism a source of ancient wisdom that could be harmonized with Christian teachings and classical philosophy.

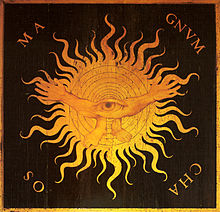

The idea of prima materia has roots in Greco-Roman traditions, particularly in Orphic cosmogony, where it is linked to the cosmic egg, and in the biblical concept of Tehom from Genesis, reflecting a synthesis of classical and Christian thought during the Renaissance.

[6] In alchemy, prima materia is the substance that undergoes transformation through processes such as nigredo, the blackening stage associated with chaos, which ultimately leads to the creation of the philosopher's stone.

[15] The significance of prima materia in Hermeticism lies in its representation of the potential for both material and spiritual transformation, embodying the Hermetic principle of "as above, so below", where the macrocosm and microcosm reflect each other in the alchemical process.

[9] Hermeticists adhere to the doctrine of prisca theologia, the belief that a single, true theology exists, which is present in all religions and was revealed by God to humanity in antiquity.

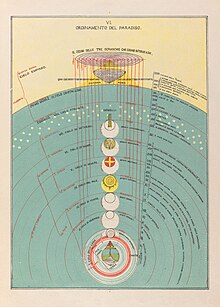

Then God orders the elements into the seven heavens (often held to be the spheres of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Sun, and the Moon, which travel in circles and govern destiny).

[27] The alternative account of the fall of man, as preserved in Isis the Prophetess to Her Son Horus, describes a process in which God, after creating the universe and various deities, fashioned human souls from a mysterious substance and assigned them to dwell in the astral region.

[40] The work of such writers as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who attempted to reconcile Jewish kabbalah and Christian mysticism, brought Hermeticism into a context more easily understood by Europeans during the time of the Renaissance.

[44] While Yates's thesis has since been largely rejected,[45] the important role played by the 'Hermetic' science of alchemy in the thought of such figures as Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580–1644), Robert Boyle (1627–1691) or Isaac Newton (1642–1727) has been amply demonstrated.

"[54] According to Geza Vermes, Hermeticism was a Hellenistic mysticism contemporaneous with the Fourth Gospel, and Hermes Tresmegistos was "the Hellenized reincarnation of the Egyptian deity Thoth, the source of wisdom, who was believed to deify man through knowledge (gnosis).

Unlike purely magical operations aimed at influencing the physical world, theurgical practices are intended to bring the practitioner into direct contact with the divine.

[66] Hermeticism, like many esoteric traditions, has faced criticism and sparked controversy over the centuries, particularly in relation to its origins, authenticity, and role in modern spiritual and occult movements.

Some researchers argue that the Corpus Hermeticum and other Hermetic writings are not the remnants of ancient wisdom but rather syncretic works composed during the Hellenistic period, blending Greek, Egyptian, and other influences.

[70] Hermeticism has left a profound legacy on Western thought, influencing a wide range of esoteric traditions, philosophical movements, and cultural expressions.

The Renaissance saw a revival of Hermeticism, particularly through the works of scholars like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who integrated Hermetic teachings into Christian theology and philosophy.

[9] The Hermetic principle of "as above, so below" and the concept of prisca theologia—the idea that all true knowledge and religion stem from a single ancient source—became central tenets in these esoteric movements.

For example, the works of William Blake, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Jorge Luis Borges contain elements of Hermetic philosophy, particularly its themes of spiritual ascent, divine knowledge, and the unity of all things.

[15] In modern literature, Hermetic motifs can be seen in the works of authors like Umberto Eco, John Crowley, and Dan Brown, who explore themes of hidden knowledge, secret societies, and the mystical connections between the microcosm and macrocosm.