Higgs mechanism

In the Standard Model, the phrase "Higgs mechanism" refers specifically to the generation of masses for the W±, and Z weak gauge bosons through electroweak symmetry breaking.

[2] The mechanism was proposed in 1962 by Philip Warren Anderson,[3] following work in the late 1950s on symmetry breaking in superconductivity and a 1960 paper by Yoichiro Nambu that discussed its application within particle physics.

[a][14] The Higgs mechanism was incorporated into modern particle physics by Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam, and is an essential part of the Standard Model.

In the Standard Model, at temperatures high enough that electroweak symmetry is unbroken, all elementary particles are massless.

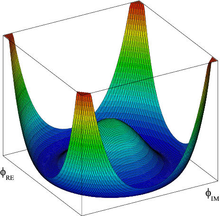

At a critical temperature, the Higgs field develops a vacuum expectation value; some theories suggest the symmetry is spontaneously broken by tachyon condensation, and the W and Z bosons acquire masses (also called "electroweak symmetry breaking", or EWSB).

[15] Fermions, such as the leptons and quarks in the Standard Model, can also acquire mass as a result of their interaction with the Higgs field, but not in the same way as the gauge bosons.

The Higgs field, through the interactions specified (summarized, represented, or even simulated) by its potential, induces spontaneous breaking of three out of the four generators ("directions") of the gauge group U(2).

This is often written as SU(2)L × U(1)Y, (which is strictly speaking only the same on the level of infinitesimal symmetries) because the diagonal phase factor also acts on other fields – quarks in particular.

Rotating the coordinates so that the second basis vector points in the direction of the Higgs boson makes the vacuum expectation value of H the spinor ( 0, v ) .

In spite of the introduction of spontaneous symmetry breaking, the mass terms preclude chiral gauge invariance.

The quantities γμ are the Dirac matrices, and Gψ is the already-mentioned Yukawa coupling parameter for ψ.

Spontaneous symmetry breaking offered a framework to introduce bosons into relativistic quantum field theories.

[16] The only observed particles which could be approximately interpreted as Goldstone bosons were the pions, which Yoichiro Nambu related to chiral symmetry breaking.

This was done in Philip Warren Anderson's 1962 paper[3] but only in non-relativistic field theory; it also discussed consequences for particle physics but did not work out an explicit relativistic model.

The mechanism is closely analogous to phenomena previously discovered by Yoichiro Nambu involving the "vacuum structure" of quantum fields in superconductivity.

In spite of the large values involved (see below) this permits a gauge theory description of the weak force, which was independently developed by Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam in 1967.

[29][30][31] One of the first times the Higgs name appeared in print was in 1972 when Gerardus 't Hooft and Martinus J. G. Veltman referred to it as the "Higgs–Kibble mechanism" in their Nobel winning paper.

A charged scalar field must also be complex (or described another way, it contains at least two components, and a symmetry capable of rotating each into the other(s)).

However it turns out that fixing the choice of gauge so that the condensate has the same phase everywhere, also causes the electromagnetic field to gain an extra term.

Interaction with the quantum fluid filling the space prevents certain forces from propagating over long distances (as it does inside a superconductor; e.g., in the Ginzburg–Landau theory).

The Meissner effect arises due to currents in a thin surface layer, whose thickness can be calculated from the simple model of Ginzburg–Landau theory, which treats superconductivity as a charged Bose–Einstein condensate.

If the condensate were neutral, the flow would be along the gradients of θ, the direction in which the phase of the Schrödinger field changes.

The description of a Bose–Einstein condensate of loosely bound pairs is actually more difficult than the description of a condensate of elementary particles, and was only worked out in 1957 by John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and John Robert Schrieffer in the famous BCS theory.

This is an example of configuring the model to conform to Goldstone's theorem: Spontaneously broken continuous symmetries (normally) produce massless excitations.

Furthermore, choosing a gauge where the phase of the vacuum is fixed, the potential energy for fluctuations of the vector field is nonzero.

picks out a canonical trivialization which breaks the right-invariance of the principal bundle that the gauge theory lives on.

In physics, one generally works under an implicit global trivialization and rarely in the more abstract principal bundle.

Ernst Stueckelberg discovered[35] a version of the Higgs mechanism by analyzing the theory of quantum electrodynamics with a massive photon.

By making a gauge transformation to set θ = 0 , the gauge freedom in the action is eliminated, and the action becomes that of a massive vector field: To have arbitrarily small charges requires that the U(1) is not the circle of unit complex numbers under multiplication, but the real numbers ℝ under addition, which is only different in the global topology.

Among the allowed gauge groups, only non-compact U(1) admits affine representations, and the U(1) of electromagnetism is experimentally known to be compact, since charge quantization holds to extremely high accuracy.