High-speed rail in the United Kingdom

[2] Government-backed plans to provide east–west high-speed services between cities in the North of England are also in development, as part of the Northern Powerhouse Rail project.

During the age of steam locomotion, the British railway industry strove to develop reliable technology for powering high-speed rail services between major cities.

This line was an ambitious project led by railway entrepreneur Sir Edward Watkin who envisaged a Liverpool-Paris route crossing from Britain to France via a proposed channel tunnel.

[4] Although the tunnel scheme was not realised by this railway company, the route operated services between Sheffield Victoria and London Marylebone via Leicester Central, with the dedicated express track beginning at Annesley in Nottinghamshire.

Various claims exist for the first locomotive to break the 100 mph (161 km/h) barrier, notably the Great Western Railway's City of Truro (1904) and the LNER's Flying Scotsman (1934).

It was equipped with the C-APT in Cab signalling system, and a tilting mechanism which allowed the train to tilt into bends to reduce cornering forces on passengers, and was powered by gas turbines (the first to be used on British Rail since the Great Western Railway, and subsequent Western Region utilised Swiss built Brown-Boveri, and British built Metropolitan Vickers locomotives (18000 and 18100) in the early 1950s).

The 1970s oil crisis prompted a rethink in the choice of motive power (as with the prototype TGV in France), and British Rail later opted for traditional electric overhead lines when the pre-production and production APTs were brought into service in 1980–86.

The APT was, however, beset with technical problems; financial constraints and negative media coverage eventually caused the project to be cancelled.

[10] During the same period, British Rail also invested in a separate, parallel project to design a train based on conventional technology as a stopgap.

[15] The nine-car trains were constructed by Alstom and are equipped with a tilting mechanism developed by Fiat to enable them to run at high speeds on existing rail infrastructure, thus fulfilling the aims of the APT project some 30 years later.

After a lengthy process of route selection and public enquiries in the second half of the 1990s, work got under way on Section 1 from the Channel Tunnel to west of the Medway in 1998 and the line opened in 2003.

The Greengauge 21 study states that the total route length, including the connections to the existing network and High Speed One, would be 150 miles (240 km).

[22] The rest of the funding would go into the Network North programme, which consists of hundreds of transport projects mostly in Northern England and Midlands, including new high-speed lines linking up major cities and new railway hubs.

When the InterCity East Coast franchise (then operated by GNER) came up for its first renewal, Virgin Rail Group raised the idea in 2000 of constructing new track and purchasing a new fleet of trains for the line.

Publicity material featuring Virgin branded TGV and ICE trains appeared, and it was stated that the stock would be built in Birmingham.

Journey times from London given included: Although First stated that this report would be published and given to the SRA and government, little has been heard of the plan since the initial press release.

[26][27][28] In 2010 Cardiff city council again lobbied central government for a high-speed rail line to London via Bristol,[29] then estimated to contribute £2.2 billion to the Welsh economy.

[34] Most of the press continued to take this line when the report was finally published, drawing scorn from both opposition parties, Labour back-benchers and transport pressure groups alike.

Even if a transformation in connectivity could be achieved, the evidence is very quiet on the scale of resulting economic benefit, and in France business use of the high speed train network is low.

An alternative argument is sometimes made on environmental grounds because a very high speed line from London to Scotland could attract modal shift from air.

[36] It evaluated options for high-speed rail in the UK and recommended an £11bn route from London St Pancras and Heathrow to Birmingham and the North West, which they dubbed HS2.

[40] The report outlined the government's strategic plan for the railways until 2037 which recommended "further study" and stated that dedicated magnetic levitation system and freight lines were "too expensive".

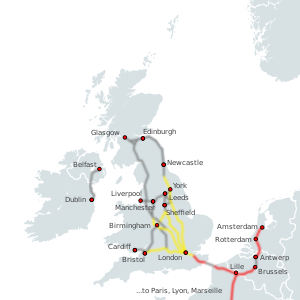

The headline proposal was its plan for a new high-speed rail line between London and Glasgow/Edinburgh, following a route through the West Midlands and the North-West of England.

The HST applied what had been learned so far to traditional technology – a project parallel to the APT but based on conventional principles while incorporating the newly discovered knowledge of wheel/rail interaction and suspension design.

The prototype class 252 (power cars 43000 and 43001) took the world record for diesel traction, achieving 143.2 mph (230 km/h) on 12 June 1973 on the East Coast Main Line between Northallerton and Thirsk.

On 27 September 1985 a shortened class 254 set carrying passengers ran non-stop from Newcastle to London King's Cross, averaging 115.4 mph.

These units allowed TransPennine Express to begin services up the East Coast Main Line to Edinburgh from Manchester Piccadilly.

The following table lists the rolling stock operating or having operated in Great Britain that is capable of a top speed of 125 mph or greater: The recent interest in high-speed rail generated by the success of the CTRL has led to the formation of several companies and non-profit groups aiming to further the construction of domestic high-speed lines in Britain.

Eleven big cities announced a joint campaign for a high-speed rail network serving the entire of Great Britain on 9 September 2009.

Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham and Sheffield stated as their goal that The campaign will be deliberately focused on the importance of building a whole network to link all our major economic centres together, not simply a sterile debate about where a first route should go.