Highland branch

Amid a backdrop of failing private passenger service in the United States, it was the first time a government entity in that country had assumed full responsibility for losses on a route.

[3] Brookline had previously only been reachable by road (horsecar service on what is now Huntington Avenue did not begin until 1859), and the branch was quickly a success.

[4][5] Based on this success, the Charles River Branch Railroad was founded in 1849 to extend service west from Brookline.

[6][7] The line was further extended to Great Plains (later part of Needham) the next year, and to Woonsocket, Rhode Island in 1863.

From 1858, freight trains carrying gravel from Needham quarries to fill the Back Bay for development made up most of the traffic on the line.

[17] The line's elevation was lowered by as much as 10.5-foot (3.2 m) in some places in order to permit road traffic to cross overhead.

The New York Central studied third-rail electrification of the Highland branch and the main line as far as Framingham in 1911, but did not find it to be cost-effective.

[21] Trains which traveled from Boston to Riverside via the Highland branch returned via the main line, thus completing the "circuit".

[23] After the Needham cutoff opened in 1906, the New Haven rerouted most trains on the Charles River line via Forest Hills rather than the Highland branch to avoid congestion at the Cook Street junction.

This frequency dropped by one-quarter by 1919 (with many Highland branch trains not completing the circuit on the main line), then stayed constant for two decades.

[17] The Massachusetts state legislature had first proposed replacing the conventional train service on the Highland branch with streetcars running from the Tremont Street Subway in 1926.

Causes included high structural costs of doing business, loss of demand outside of rush hour, and restrictive regulations.

[30] The Boston-area railroads were not immune to these trends, and as the decade wore on sought to end or reduce their money-losing commuter operations.

[32] The Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) first proposed buying the Highland branch and rebuilding it as a light rail line in 1956, for a total estimated cost of $9 million.

From June 1960 to January 1961, the MTA enlarged Riverside Yard and added a maintenance facility, upgraded the power infrastructure, and improved the signalling system.

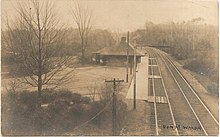

[45] The Highland branch diverged from the Boston and Albany main line at Brookline Junction, adjacent to Fenway Park.

An even closer encounter took place in Newton Centre, where the line ran within a few feet of Crystal Lake.

The grade crossing elimination project of 1905–1907 lowered the line in this area to 18 inches (460 mm) above the lake's surface level.

[47] At Newton Highlands the New York and New England Railroad diverged at Cook Street Junction for Woonsocket.

[25] The creation of the circuit service over the Highland branch coincided with a "major program of capital investment and improvements" by the Boston and Albany.

[49] After Richardson's death in 1886, his successor firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge designed a number of additional stations for the B&A, several of which were for the Highland branch.

[51] Ignored in this renewal program was the circa-1870 Brookline station, dismissed by Charles Mulford Robinson in 1902 as "disappointing...a brick structure of an earlier date.