Enriched uranium

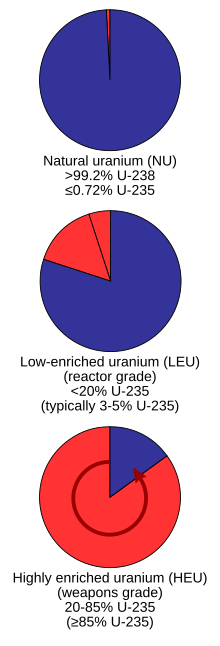

Uranium as it is taken directly from the Earth is not suitable as fuel for most nuclear reactors and requires additional processes to make it usable (CANDU design is a notable exception).

Reprocessed uranium often carries traces of other transuranic elements and fission products, necessitating careful monitoring and management during fuel fabrication and reactor operation.

The fissile uranium in nuclear weapon primaries usually contains 85% or more of 235U known as weapons grade, though theoretically for an implosion design, a minimum of 20% could be sufficient (called weapon-usable) although it would require hundreds of kilograms of material and "would not be practical to design";[11][12] even lower enrichment is hypothetically possible, but as the enrichment percentage decreases the critical mass for unmoderated fast neutrons rapidly increases, with for example, an infinite mass of 5.4% 235U being required.

Wrapping the weapon's fissile core in a neutron reflector (which is standard on all nuclear explosives) can dramatically reduce the critical mass.

The critical mass for 85% highly enriched uranium is about 50 kilograms (110 lb), which at normal density would be a sphere about 17 centimetres (6.7 in) in diameter.

This multi-stage design enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of nuclear weapons, allowing for greater control over the release of energy during detonation.

For the secondary of a large nuclear weapon, the higher critical mass of less-enriched uranium can be an advantage as it allows the core at explosion time to contain a larger amount of fuel.

[17] The medical industry benefits from the unique properties of highly enriched uranium, which enable the efficient production of critical isotopes essential for diagnostic imaging and therapeutic applications.

The S-50 plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was used during World War II to prepare feed material for the Electromagnetic isotope separation (EMIS) process, explained later in this article.

It requires much less energy to achieve the same separation than the older gaseous diffusion process, which it has largely replaced and so is the current method of choice and is termed second generation.

[19] In August 2011 Global Laser Enrichment, a subsidiary of GEH, applied to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for a permit to build a commercial plant.

[28] In September 2012, the NRC issued a license for GEH to build and operate a commercial SILEX enrichment plant, although the company had not yet decided whether the project would be profitable enough to begin construction, and despite concerns that the technology could contribute to nuclear proliferation.

[24] Due to these concerns the American Physical Society filed a petition with the NRC, asking that before any laser excitation plants are built that they undergo a formal review of proliferation risks.

They in general have the disadvantage of requiring complex systems of cascading of individual separating elements to minimize energy consumption.

The Uranium Enrichment Corporation of South Africa (UCOR) developed and deployed the continuous Helikon vortex separation cascade for high production rate low-enrichment and the substantially different semi-batch Pelsakon low production rate high enrichment cascade both using a particular vortex tube separator design, and both embodied in industrial plant.

[31] A demonstration plant was built in Brazil by NUCLEI, a consortium led by Industrias Nucleares do Brasil that used the separation nozzle process.

A production-scale mass spectrometer named the calutron was developed during World War II that provided some of the 235U used for the Little Boy nuclear bomb, which was dropped over Hiroshima in 1945.

The French CHEMEX process exploited a very slight difference in the two isotopes' propensity to change valency in oxidation/reduction, using immiscible aqueous and organic phases.

Efficient utilization of separative work is crucial for optimizing the economic and operational performance of uranium enrichment facilities.

Downblending is a key process in nuclear non-proliferation efforts, as it reduces the amount of highly enriched uranium available for potential weaponization while repurposing it for peaceful purposes.

The HEU feedstock can contain unwanted uranium isotopes: 234U is a minor isotope contained in natural uranium (primarily as a product of alpha decay of 238U—because the half-life of 238U is much larger than that of 234U, it is be produced and destroyed at the same rate in a constant steady state equilibrium, bringing any sample with sufficient 238U content to a stable ratio of 234U to 238U over long enough timescales); during the enrichment process, its concentration increases but remains well below 1%.

Concentrations of these isotopes in the LEU product in some cases could exceed ASTM specifications for nuclear fuel if NU or DU were used.

So, the HEU downblending generally cannot contribute to the waste management problem posed by the existing large stockpiles of depleted uranium.

Effective management and disposition strategies for depleted uranium are crucial to ensure long-term safety and environmental protection.

Innovative approaches such as reprocessing and recycling of depleted uranium could offer sustainable solutions to minimize waste and optimize resource utilization in the nuclear fuel cycle.

A major downblending undertaking called the Megatons to Megawatts Program converts ex-Soviet weapons-grade HEU to fuel for U.S. commercial power reactors.

The decommissioning programme of Russian nuclear warheads accounted for about 13% of total world requirement for enriched uranium leading up to 2008.

[34][35] This innovative program not only facilitated the safe and secure elimination of excess weapons-grade uranium but also contributed to the sustainable operation of civilian nuclear power plants, reducing reliance on newly enriched uranium and promoting non-proliferation efforts globally The following countries are known to operate enrichment facilities: Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Japan, the Netherlands, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

[40] It has also been claimed that Israel has a uranium enrichment program housed at the Negev Nuclear Research Center site near Dimona.

[42] This covert terminology underscores the secrecy and sensitivity surrounding the production of highly enriched uranium during World War II, highlighting the strategic importance of the Manhattan Project and its role in the development of nuclear weapons.