Hilary Putnam

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (/ˈpʌtnəm/; July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American philosopher, mathematician, computer scientist, and figure in analytic philosophy in the second half of the 20th century.

[17] In his later work, Putnam became increasingly interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics, engaging with a wider array of philosophical traditions.

[20] His father, Samuel Putnam, was a scholar of Romance languages, columnist, and translator who wrote for the Daily Worker, a publication of the American Communist Party, from 1936 to 1946.

[8] In early 1927, six months after Hilary's birth, the family moved to France, where Samuel was under contract to translate the surviving works of François Rabelais.

[23][25][26] Rebelling against the antisemitism they experienced during their youth, the Putnams decided to establish a traditional Jewish home for their children.

Putnam became an official faculty advisor to the Students for a Democratic Society and in 1968 a member of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP).

[31] In 1997, at a meeting of former draft resistance activists at Boston's Arlington Street Church, he called his involvement with the PLP a mistake.

He continued to be forthright and progressive in his political views, as expressed in the articles "How Not to Solve Ethical Problems" (1983) and "Education for Democracy" (1993).

His most noted original contributions to that field came in several key papers published in the late 1960s that set out the hypothesis of multiple realizability.

Putnam then took his argument a step further, asking about such things as the nervous systems of alien beings, artificially intelligent robots and other silicon-based life forms.

Putnam concluded that type-identity theorists had been making an "ambitious" and "highly implausible" conjecture that could be disproved by one example of multiple realizability.

[39][40]: 637 Putnam, Jerry Fodor, and others argued that along with being an effective argument against type-identity theories, multiple realizability implies that any low-level explanation of higher-level mental phenomena is insufficiently abstract and general.

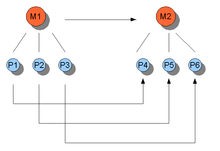

This formulation, now called "machine-state functionalism", was inspired by analogies Putnam and others made between the mind and Turing machines.

[50] Ian Hacking called Representation and Reality (1988) a book that "will mostly be read as Putnam's denunciation of his former philosophical psychology, to which he gave the name 'functionalism'.

[52] Putnam's change of mind was primarily due to the difficulties computational theories have in explaining certain intuitions with respect to the externalism of mental content.

[56] Functionalism helped lay the foundations for modern cognitive science[56] and was the dominant theory of mind in philosophy in the last part of the 20th century.

John Searle's Chinese room argument (1980) is a direct attack on the claim that thought can be represented as a set of functions.

This argument attempts to show that systems that operate merely on syntactic processes cannot realize any semantics (meaning) or intentionality (aboutness).

Searle thus attacks the idea that thought can be equated with following a set of syntactic rules and concludes that functionalism is an inadequate theory of the mind.

Thanks to Putnam, Saul Kripke, Tyler Burge and others, Davidson said, philosophy could now take the objective realm for granted and start questioning the alleged "truths" of subjective experience.

[39][non-primary source needed] Since there is no limit to the number of such expressions to be considered, Putnam embraced a form of semantic holism.

[71]: 61–62 Putnam also held the view that mathematics, like physics and other empirical sciences, uses both strict logical proofs and "quasi-empirical" methods.

Also, together with a separate paper with his student Richard Boyd and Gustav Hensel, he demonstrated how the Davis–Mostowski–Kleene hyperarithmetical hierarchy of arithmetical degrees can be naturally extended up to

[6] In epistemology, Putnam is known for his argument against skeptical scenarios based on the "brain in a vat" thought experiment (a modernized version of Descartes's evil demon hypothesis).

By arguing that such a scenario is impossible, Putnam attempts to show that this notion of a gap between one's concept of the world and the way it is is absurd.

[84] Crispin Wright argues that Putnam's formulation of the brain-in-a-vat scenario is too narrow to refute global skepticism.

[81] In the late 1970s and the 1980s, stimulated by results from mathematical logic and by some of Quine's ideas, Putnam abandoned his long-standing defense of metaphysical realism—the view that the categories and structures of the external world are both causally and ontologically independent of the conceptualizations of the human mind—and adopted a rather different view, which he called "internal realism" or "pragmatic realism".

He thus accepted "conceptual relativity"—the view that it may be a matter of choice or convention, e.g., whether mereological sums exist, or whether spacetime points are individuals or mere limits.

He advanced different versions of quantum logic over the years,[100] and eventually turned away from it in the 1990s, due to critiques by Nancy Cartwright, Michael Redhead, and others.

[97] In the mid-1970s, Putnam became increasingly disillusioned with what he perceived as modern analytic philosophy's "scientism" and focus on metaphysics over ethics and everyday concerns.