Hildegard of Bingen

[13] From early childhood, long before she undertook her public mission or even her monastic vows, Hildegard's spiritual awareness was grounded in what she called the umbra viventis lucis, the reflection of the living Light.

Her letter to Guibert of Gembloux, which she wrote at the age of 77, describes her experience of this light: From my early childhood, before my bones, nerves, and veins were fully strengthened, I have always seen this vision in my soul, even to the present time when I am more than seventy years old.

In this vision, my soul, as God would have it, rises up high into the vault of heaven and into the changing sky and spreads itself out among different peoples, although they are far away from me in distant lands and places.

[17] In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed together at Disibodenberg and formed the core of a growing community of women attached to the monastery of monks, named a Frauenklause, a type of female hermitage.

[18] The written record of the Life of Jutta indicates that Hildegard probably assisted her in reciting the psalms, working in the garden, other handiwork, and tending to the sick.

[30] In her first theological text, Scivias ("Know the Ways"), Hildegard describes her struggle within: But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [the nun Richardis von Stade] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above, I set my hand to the writing.

While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition; and, raising myself from illness by the strength I received, I brought this work to a close – though just barely – in ten years. [...]

In these volumes, the last of which was completed when she was well into her seventies, Hildegard first describes each vision, whose details are often strange and enigmatic, and then interprets their theological contents in the words of the "voice of the Living Light.

Scivias is a contraction of Sci vias Domini ('Know the Ways of the Lord'), and it was Hildegard's first major visionary work, and one of the biggest milestones in her life.

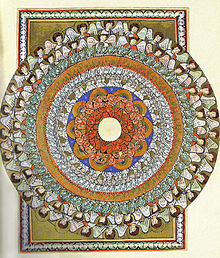

[51] Towards the end of her life, Hildegard commissioned a richly decorated manuscript of Scivias (the Rupertsberg Codex); although the original has been lost since its evacuation to Dresden for safekeeping in 1945, its images are preserved in a hand-painted facsimile from the 1920s.

[6] In her second volume of visionary theology, Liber Vitae Meritorum, composed between 1158 and 1163, after she had moved her community of nuns into independence at the Rupertsberg in Bingen, Hildegard tackled the moral life in the form of dramatic confrontations between the virtues and the vices.

Each vice, although ultimately depicted as ugly and grotesque, nevertheless offers alluring, seductive speeches that attempt to entice the unwary soul into their clutches.

[53] Hildegard's descriptions of the possible punishments there are often gruesome and grotesque, which emphasize the work's moral and pastoral purpose as a practical guide to the life of true penance and proper virtue.

[54] Hildegard's last and grandest visionary work, Liber divinorum operum, had its genesis in one of the few times she experienced something like an ecstatic loss of consciousness.

The final vision (3.5) contains Hildegard's longest and most detailed prophetic program of the life of the church from her own days of "womanish weakness" through to the coming and ultimate downfall of the Antichrist.

[57] Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Catholic Church has led to a great deal of popular interest in Hildegard's music.

[61][62] In addition to the Ordo Virtutum, Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum.

Scholars such as Margot Fassler, Marianne Richert Pfau, and Beverly Lomer also note the intimate relationship between music and text in Hildegard's compositions, whose rhetorical features are often more distinct than is common in 12th-century chant.

These books are historically significant because they show areas of medieval medicine that were not well documented because their practitioners, mainly women, rarely wrote in Latin.

[70] The nearly three hundred chapters of the second book of Causae et Curae "explore the etiology, or causes, of disease as well as human sexuality, psychology, and physiology.

"[41] In this section, she gives specific instructions for bleeding based on various factors, including gender, the phase of the moon (bleeding is best done when the moon is waning), the place of disease (use veins near diseased organ or body part) or prevention (big veins in arms), and how much blood to take (described in imprecise measurements, like "the amount that a thirsty person can swallow in one gulp").

In the third and fourth sections, Hildegard describes treatments for malignant and minor problems and diseases according to the humoral theory, again including information on animal health.

[70] Finally, the sixth section documents a lunar horoscope to provide an additional means of prognosis for both disease and other medical conditions, such as conception and the outcome of pregnancy.

This disharmony reflects that introduced by Adam and Eve in the Fall, which for Hildegard marked the indelible entrance of disease and humoral imbalance into humankind.

These sores and openings create a certain storm and smoky moisture in men, from which the flegmata arise and coagulate, which then introduce diverse infirmities to the human body.

[42] Higley believes that "the Lingua is a linguistic distillation of the philosophy expressed in her three prophetic books: it represents the cosmos of divine and human creation and the sins that flesh is heir to.

"[42] The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin, encompassing many invented, conflated, and abridged words.

[88] She conducted four preaching tours throughout Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in chapter houses and in public, mainly denouncing clerical corruption and calling for reform.

[110] Sophiologist Robert Powell writes that hermetic astrology proves the match,[111] while mystical communities in Hildegard's lineage include that of artist Carl Schroeder[112] as studied by Columbia sociologist Courtney Bender[113] and supported by reincarnation researchers Walter Semkiw and Kevin Ryerson.

[126] In his book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, neurologist Oliver Sacks devotes a chapter to Hildegard and concludes that in his opinion her visions were migrainous.