Hilina Slump

[4] Kīlauea's entire south flank, extending out to Cape Kumukahi, is currently sliding seaward,[5] with some parts of the central portion (overlooking the Hilina slump) moving as much as 10 centimeters (3.9 inches) per year,[6] pushed by the forceful injection of magma and pulled by gravity.

[7] Current movement of the Hilina slump and recent volcanic activity, coupled with evidence of massive submarine slides in the geological past, has led to claims that megatsunamis might result if the south flank of Kīlauea should suddenly fail.

[10] The largest, at the trailing edge of the island, is Mauna Loa Volcano, and on its seaward flank is the younger Kīlauea, with the still submerged Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount (formerly Lōʻihi) just off-shore.

[14] The weight of the rock mass causes extension (stretching) downhill, favoring the formation of vertical structures, such as dip-slip faults and rift zones, parallel to the slope.

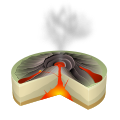

[15] On Kīlauea's seaward flank (where it is not resting against Mauna Loa) these tendencies are evident where magma oozing out of the caldera turns east and west to form the Southwest Rift Zone (SWRZ) and East Rift Zone (ERZ), both parallel to the shore,[17] and also in the cliffs of the Hilina Pali – coincident with dip-slip faults of the Hilina fault system – which form the head-scarp where a large block of rock has slumped down and outward.

They also serve as wedges, forcing the south flank of Kīlauea downslope across a décollement – a nearly horizontal fault where the volcanic deposits rest on the oceanic crust[18] – about 8 to 10 km deep.

[20] On the central portion of the south flank of Kīlauea the thousand-foot high cliffs of the Hilina Pali and similar scarps were recognized as early as 1930 as headscarps resulting from slumping of the coast.

[5] With the discovery in the late 1980s that the entire south flank of Kīlauea is involved with submarine landslides the term "Hilina slump" has been applied by some scientists to the broader area.

According to one account, the tsunami "rolled in over the tops of the coconut trees, probably 60 feet (18 m) high ... inland a distance of a quarter of a mile [0.4 km] in some places, taking out to sea when it returned, houses, men, women, and almost everything movable.

[34] The breadth and gentle slopes of young shield volcanoes such as Kīlauea are in contrast to the steep, picturesque cliffs (pali), deeply incised canyons, and narrow ridges typical of the older islands, and for a long while it was a bit of mystery how the latter got that way.

[35] However, that such mass wasting was a ubiquitous feature of Hawaiian geology was not recognized until systematic mapping of the sea floor in the late 1980s[36] identified 17 areas on the flanks of the islands that appear to be the remnants of large landslides.

[43] Debris avalanches, or flows, "commonly represent a single episode of rapid failure",[44] where the potential energy of the slide is released suddenly, and could cause giant tsunamis.

[50] Coupled with the knowledge that the Hawaiian islands are ringed with debris fans where large portions of the various volcanoes have slid into the sea[51] – the volume of the Hilina slump has been estimated at 10,000 to 12,000 cubic kilometers (2,400 to 2,900 cu mi)[52] – it seems reasonable to consider the risk of volcanic and seismic activity in Hawaiʻi wreaking havoc around the Pacific Rim.