Hindenburg disaster

[4][5] After opening its 1937 season by completing a single round-trip passage to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in late March, the Hindenburg departed from Frankfurt, Germany, on the evening of May 3, on the first of ten round trips between Europe and the United States that were scheduled for its second year of commercial service.

Advised of the poor weather conditions at Lakehurst, Captain Max Pruss charted a course over Manhattan Island, causing a public spectacle as people rushed out into the street to catch sight of the airship.

As this would leave much less time than anticipated to service and prepare the airship for its scheduled departure back to Europe, the public was informed that they would not be permitted at the mooring location or be able to come aboard the Hindenburg during its stay in port.

At 7:17 p.m., the wind shifted direction from east to southwest, and Captain Pruss ordered a second sharp turn starboard, making an s-shaped flightpath towards the mooring mast.

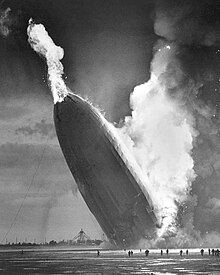

Eyewitness statements disagree as to where the fire initially broke out; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin near the ventilation shaft of cells 4 and 5.

Inside the airship, helmsman Helmut Lau, who was stationed in the lower fin, testified hearing a muffled detonation and looked up to see a bright reflection on the front bulkhead of gas cell 4, which "suddenly disappeared by the heat".

One analysis by NASA's Addison Bain gives the flame front spread rate across the fabric skin as about 49 ft/s (15 m/s) at some points during the crash, which would have resulted in a total destruction time of about 16 seconds.

German victims were memorialized in a similar manner to fallen war heroes, and grassroots movements to fund zeppelin construction (as happened after the 1908 crash of the LZ 4) were expressly forbidden by the Nazi government.

Just over twice as many (73 of 76 on board) had perished when the helium-filled U.S. Navy scout airship USS Akron crashed at sea off the New Jersey coast four years earlier on April 4, 1933.

He injured his ankle nonetheless, and was dazedly crawling away when a member of the ground crew came up, slung the diminutive Späh under one arm, and ran him clear of the fire.

At the time of the disaster, sabotage was commonly put forward as the cause of the fire, initially by Hugo Eckener, former head of the Zeppelin Company and the "old man" of German airships.

By the time he left the hotel the next morning to travel to Berlin for a briefing on the disaster, the only answer that he had for the reporters waiting outside to question him was that based on what he knew, the Hindenburg had "exploded over the airfield"; sabotage might be a possibility.

In a 1960 interview conducted by Kenneth Leish for Columbia University's Oral History Research Office, Pruss said early dirigible travel was safe, and therefore he strongly believed that sabotage was to blame.

[36] Although Mooney alleges that three Luftwaffe officers were aboard to investigate a potential bomb threat, there is no evidence they were on board to do so, and military observers were present on previous flights to study navigational techniques and weather forecasting practices of the airship crew.

According to his wife, Evelyn, Späh was quite upset over the accusations – she later recalled that her husband was outside their home cleaning windows when he first learned that he was suspected of sabotaging the Hindenburg, and was so shocked by the news that he almost fell off the ladder on which he was standing.

[39] Some more sensational newspapers claimed that a Luger pistol with one round fired was found among the wreckage and speculated that a person on board committed suicide or shot the airship.

The use of graphite dope was not publicized and I doubt if its use was widely known at the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin.In addition to Dick's observations, during the Graf Zeppelin II's early test flights, measurements were taken of the airship's static charge.

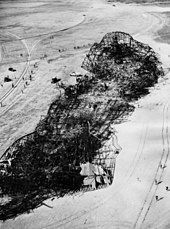

It also finds that there likely was a leak of hydrogen gas at the Hindenburg's stern, as evidenced by the difficulty the crew had in bringing the airship in trim prior to the landing (its aft was too low).

Once the ropes dropped, charge would continue building on the skin and, according to his calculations, the additional time required to produce a spark would be slightly under four minutes, in close agreement with the investigation report.

[39] A ground crew member, R.H. Ward, reported seeing the fabric cover of the upper port side of the airship fluttering, "as if gas was rising and escaping" from the cell.

Albert Sammt, the ship's first officer who oversaw the measures to correct the stern-heaviness, initially attributed to fuel consumption and sending crewmen to their landing stations in the stern, though years later, he would assert that a leak of hydrogen had occurred.

[56] The incendiary paint theory (IPT) was proposed in 1996 by retired NASA scientist Addison Bain, stating that the doping compound of the airship was the cause of the fire, and that the Hindenburg would have burned even if it were filled with helium.

Proponents of this hypothesis argue that the coatings on the fabric contained both iron oxide and aluminum-impregnated cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) which remain potentially reactive even after fully setting.

Bain interviewed the wife of the investigation's lead scientist Max Dieckmann, and she stated that her husband had told her about the conclusion and instructed her to tell no one, presumably because it would have embarrassed the Nazi government.

However, photographs of the early stages of the fire show the gas cells of the Hindenburg's entire aft section fully aflame, and no glow is seen through the areas where the fabric is still intact.

The MythBusters team also discovered that the Hindenburg's coated skin had a higher ignition temperature than that of untreated material, and that it would initially burn slowly, but that after some time the fire would begin to accelerate considerably with some indication of a thermite reaction.

[64] Although Captain Pruss believed that the Hindenburg could withstand tight turns without significant damage, proponents of the puncture hypothesis, including Hugo Eckener, question the airship's structural integrity after being repeatedly stressed over its flight record.

Proponents posit that either of these turns could have weakened the structure near the vertical fins, causing a bracing wire to snap and puncture at least one of the internal gas cells.

He held Captains Pruss and Lehmann, and Charles Rosendahl responsible for what he viewed as a rushed landing procedure with the airship badly out of trim under poor weather conditions.

During the US inquiry, Eckener testified that he believed that the fire was caused by the ignition of hydrogen by a static spark: The ship proceeded in a sharp turn to approach for its landing.