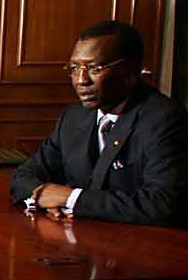

Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré (Arabic: حسين حبري Ḥusaīn Ḥabrī, Chadian Arabic: pronounced [hiˈsɛn ˈhabre]; French pronunciation: [isɛn abʁe]; 13 August 1942 – 24 August 2021),[1] also spelled Hissen Habré, was a Chadian politician and convicted war criminal who served as the 5th president of Chad from 1982 until he was deposed in 1990.

His dictatorship was notorious for widespread human rights abuses by his secret police, the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS).

He was brought to power with the support of France and the United States, who provided training, arms, and financing throughout his rule due to his opposition to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

In May 2016, Habré was found guilty by an international tribunal in Senegal of human-rights abuses, including rape, sexual slavery, and ordering the killing of 40,000 people, and sentenced to life in prison.

[10] Habré first came to international attention when a group under his command attacked the town of Bardaï in Tibesti, on 21 April 1974, and took three Europeans hostage, with the intention of ransoming them for money and arms.

The captives were a German physician, Christoph Staewen (whose wife Elfriede was killed in the attack), and two French citizens, Françoise Claustre, an archeologist, and Marc Combe, a development worker.

[15] Following his rise to power Habré created a secret police force known as the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), under which his opponents were tortured and executed.

[16] Some methods of torture commonly used by the DDS included burning the body of the detainee with incandescent objects, spraying gas into their eyes, ears and nose, forced swallowing of water, and forcing the mouths of detainees around the exhaust pipes of running automobiles.

He was accused of war crimes and torture during his eight years in power in Chad, where rights groups say that some 40,000 people were killed under his rule.

The United States and France responded by aiding Chad in an attempt to contain Libya's regional ambitions under Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi.

The treaty allowed the Chadian government to call on Libya for assistance if Chad's independence or internal security was threatened.

[9]: 191 The Libyan army was soon assisting the government forces, under Goukouni, and ousted FAN from much of northern Chad, including N'Djamena on 15 December.

Without their support, Goukouni's government troops were weakened and Habré capitalized on this and his FAN militia entered N'Djamena on 7 June 1982.

[22] In the 1980s, the United States was pivotal in bringing Hissène Habré to power, seeing him as a stalwart defense against expansion by Libya's Muammar Qaddafi, and therefore provided critical military support to his insurgency and then to his government, even as it committed widespread and systematic human rights violations—violations of which, as this report shows, many in the US government were aware.

[24] The United States also used a clandestine base in Chad to train captured Libyan soldiers whom it was organizing into an anti-Qaddafi force.

"[3] Documents obtained by Human Rights Watch show that the United States provided Habré's DDS with training, intelligence, arms, and other support despite knowledge of its atrocities.

According to the Chadian Truth Commission, the United States also provided the DDS with monthly infusions of monetary aid and financed a regional network of intelligence networks code-named "Mosaic" that Chad used to pursue suspected opponents of Habré's regime even after they fled the country.

"[3] Human rights groups hold Habré responsible for the killing of thousands of people, but the exact number is unknown.

Human Rights Watch charged him with having authorized tens of thousands of political murders and physical torture.

[26] The government of Idriss Déby established a Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes and Misappropriations Committed by Ex-President Habré, His Accomplices and/or Accessories in 1990, which reported that 40,000 people had been killed, but did not follow up on its recommendations.

Senegal did not comply, and it at first refused extradition demands from the African Union which arose after Belgium asked to try Habré.

[39] A 2007 movie by director Klaartje Quirijns, The Dictator Hunter, tells the story of the activists Souleymane Guengueng and Reed Brody who led the efforts to bring Habré to trial.

[41] 14 victims filed new complaints with a Senegalese prosecutor on 16 September, accusing Habré of crimes against humanity and torture.

failing to submit the case to its competent authorities for prosecution (obligations according to UN Convention on Torture and Other Cruel, inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) that Senegal had bound itself to).

[26] In April 2011, after initial reticence, Senegal agreed to the creation of an ad hoc tribunal in collaboration with the African Union, the Chadian state and with international funding.

The court emphasized this was a procedural matter, as the facts the victim offered during her testimony came too late in the proceedings to be included within charges of mass sexual violence committed by his security agents, the convictions for which were upheld.

[65] On 7 April 2020, a judge in Senegal granted Habre two months' leave from prison, as the jail is being used to hold new detainees in COVID-19 quarantine.