Ecclesiastical History of the English People

It is considered one of the most important original references on Anglo-Saxon history, and according to some scholars has played a key role in the development of an English national identity.

[4] These encountered a setback when Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, killed the newly Christian Edwin of Northumbria at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in about 632.

[6] The fourth book begins with the consecration of Theodore as Archbishop of Canterbury, and recounts Wilfrid's efforts to bring Christianity to the kingdom of Sussex.

[7] The fifth book brings the story up to Bede's day, and includes an account of missionary work in Frisia, and of the conflict with the British church over the correct dating of Easter.

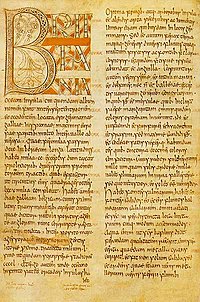

[3] Divided into five books (totalling about 400 pages), the Historia covers the history of England, ecclesiastical and political, from the time of Julius Caesar to the date of its completion in 731.

The first twenty-one chapters cover the time period before the mission of Augustine; compiled from earlier writers such as Orosius, Gildas, Prosper of Aquitaine, the letters of Pope Gregory I and others, with the insertion of legends and traditions.

After 596, documentary sources that Bede took pains to obtain throughout England and from Rome are used, as well as oral testimony, which he employed along with critical consideration of its authenticity.

Albinus, the abbot of the monastery in Canterbury, provided much information about the church in Kent, and with the assistance of Nothhelm, at that time a priest in London, obtained copies of Gregory the Great's correspondence from Rome relating to Augustine's mission.

For the early part of the work, dealing with the time up to the Gregorian mission of Augustine of Canterbury, Goffart asserts that Bede used Gildas's De excidio.

In political terms he is a partisan of his native Northumbria, amplifying its role in English history over and above that of Mercia, its great southern rival.

For while Bede is loyal to Northumbria he shows an even greater attachment to the Irish and their missionaries, whom he considers to be far more effective and dedicated than their rather complacent English counterparts.

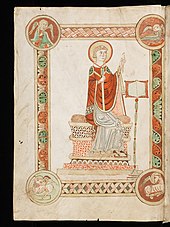

[1] One of the important themes of the Historia Ecclesiastica is that the conversion of Britain to Christianity had all been the work of Irish and Italian missionaries, with no efforts made by the native Britons.

[23] He writes approvingly of Aidan and Columba, who came from Ireland as missionaries to the Picts and Northumbrians, but disapproved of the failure of the Welsh to evangelize the invading Anglo-Saxons.

Also important is Bede's view of the conversion process as an upper-class phenomenon, with little discussion of any missionary efforts among the non-noble or royal population.

According to Farmer, Bede took this idea from Gregory the Great and illustrates it in his work by showing how Christianity brought together the native and invading races into one church.

[26] The historian Walter Goffart says of the Historia that many modern historians find it a "tale of origins framed dynamically as the Providence-guided advance of a people from heathendom to Christianity; a cast of saints rather than rude warriors; a mastery of historical technique incomparable for its time; beauty of form and diction; and, not least, an author whose qualities of life and spirit set a model of dedicated scholarship.

These were de rigueur in medieval religious narrative,[31] but Bede appears to have avoided relating the more extraordinary tales; and, remarkably, he makes almost no claims for miraculous events at his own monastery.

The chief pagan priest, Coifu, declared that he had not had as much favour from the king or success in his undertakings as many other men even though no one had served the gods more faithfully, so he saw that they had no power and he would convert to Christianity.

[3] For example, although Bede recounts Wilfrid's missionary activities, he does not give a full account of his conflict with Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury, or his ambition and aristocratic lifestyle.

[3] The omissions are not restricted to Wilfrid; Bede makes no mention at all of the English missionary Boniface, though it is unlikely he knew little of him; the final book contains less information about the church in his own day than could be expected.

Bede does shed some light on monastic affairs; in particular, he comments in book V that many Northumbrians are laying aside their arms and entering monasteries "rather than study the arts of war.

The first extensive use of "BC" (hundreds of times) occurred in Fasciculus Temporum by Werner Rolevinck in 1474, alongside years of the world (anno mundi).

[46] The Historia was translated into Old English sometime between the end of the ninth century and about 930;[47] although the surviving manuscripts are predominantly in the West Saxon dialect, it is clear that the original contained Anglian features and so was presumably by a scholar from or trained in Mercia.

[3] In the early Middle Ages, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Historia Brittonum, and Alcuin's Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Eboracensis ecclesiae all drew heavily on the text.

[56] Early modern writers, such as Polydore Vergil and Matthew Parker, the Elizabethan Archbishop of Canterbury, also utilized the Historia, and his works were used by both Protestant and Catholic sides in the Wars of Religion.

One historian, Charlotte Behr, asserts that the Historia's account of the arrival of the Germanic invaders in Kent should be considered as current myth, not history.

[58] Historian Tom Holland writes that "When, in the generations that followed Alfred, a united kingdom of England came to be forged, it was Bede's history that provided it with a sense of ancestry that reached back beyond its foundation.

Eggestein had also printed an edition of Rufinus's translation of Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History, and the two works were reprinted, bound as a single volume, on 14 March 1500 by Georg Husner, also of Strasbourg.

Smith undertook his edition under the influence of Thomas Gale, encouraged by Ralph Thoresby, and with assistance of Humfrey Wanley on Old English.

His son George brought out in 1722 the Historiæ Ecclesiasticæ Gentis Anglorum Libri Quinque, auctore Venerabili Bæda ... cura et studio Johannis Smith, S. T. P., published by Cambridge University Press.