History of African Americans in Baltimore

[4] During the Great Migration, thousands of African Americans from the Southern United States moved to Baltimore in search of better socioeconomic conditions and freedom from segregationist Jim Crow laws, lynching, and other forms of anti-black racism.

[11] Many black Baltimore residents have moved to the suburbs or returning to Southern cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Birmingham, Memphis, San Antonio and Jackson.

[15] From the late 18th century into the 1820s Baltimore was a "city of transients," a fast-growing boom town attracting thousands of ex-slaves from the surrounding countryside.

Slavery in Maryland declined steadily after the 1810s as the state's economy shifted away from plantation agriculture, as evangelicalism and a liberal manumission law encouraged slaveholders to free enslaved people held in bondage, and as other slaveholders practiced "term slavery," registering deeds of manumission but postponing the actual date of freedom for a decade or more.

With unskilled and semiskilled employment readily available in the shipyards and related industries, little friction with white workers occurred.

Churches, schools, and fraternal and benevolent associations provided a cushion against hardening white attitudes toward free people of color in the wake of Nat Turner's revolt in Virginia in 1831.

But a flood of German and Irish immigrants swamped Baltimore's labor market after 1840, driving free black people deeper into poverty.

[17] Since chemicals needed constant attention, the rapid turnover of free white labor encouraged the owner to use enslaved workers.

[18] The location of Baltimore in a border state created opportunities for enslaved people in the city to run away and find freedom in the north—as Frederick Douglass did.

Therefore, slaveholders in Baltimore frequently turned to gradual manumission as a means to secure dependable and productive labor from slaves.

In promising freedom after a fixed period of years, slaveholders intended to reduce the costs associated with lifetime servitude while providing slaves incentive for cooperation.

Enslaved people tried to negotiate terms of manumission that were more advantageous, and the implicit threat of flight weighed significantly in slaveholders' calculations.

In the midst of this change, white Baltimoreans interpreted black discontent as disrespect for law and order, which justified police repression.

Establishing an unequal system that prepared white students for citizenship while using education to reinforce black subjugation, Baltimore's postwar school system exposed the contradictions of race, education, and republicanism in an age when African Americans struggled to realize the ostensible freedoms gained by emancipation.

William Alexander and his newspaper, the Afro American, that economic advancement and first-class citizenship depended on equal access to schools.

Two years later, however, Maryland passed a law requiring railroad companies to operate separate cars and coaches for white and colored passengers.

African Americans moving from the South and rural areas with little money and limited job opportunities compromised living conditions by seeking cheaper housing and sharing apartments designed for single-families across multiple large families.

Milton Dashiell advocated for an ordinance to bar African Americans from moving into the Eutaw Place neighborhood in northwest Baltimore.

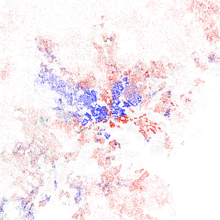

[29][30] Although Baltimore had experienced an influx in its African American population around the turn of the century, the start of the First World War and the increased availability of urban industry jobs spurred the Great Migration, leading Baltimore like other Northern cities to experience a surge in its African American population, particularly around its ports.

In response to the 1917 supreme court decision that abolished residential segregation and the influx of African American migrants, Mayor James H. Preston ordered housing inspectors to report anyone who rented or sold property to black people in predominantly white neighborhoods.

The Party was initially organized informally at the Soul School on 522 North Fremont Avenue near the George P. Murphy Homes.

[36] The now-defunct center was intended as a safe place for LGBT people of color and offered health and safety information including AIDS awareness.

[46] BCP has published original titles by notable authors including Walter Mosley, John Henrik Clarke, E. Ethelbert Miller, Yosef Ben-Jochannan, and Dorothy B. Porter, as well as reissuing significant works by Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, W. E. B.

It is the flagship newspaper of the Afro-American chain and the longest-running African-American family-owned newspaper in the United States, established in 1892 by John H. Murphy Sr.[47][48] The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture is the premier experience and best resource for information and inspiration about the lives of African American Marylanders.

Opened in 2005, the museum is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, and was named after Reginald F. Lewis, the first African American to build a billion-dollar company, TLC Beatrice International Holdings.

The museum is currently located on 1601 East North Avenue in a renovated firehouse, a Victorian Mansion, and two former apartment dwellings that provide nearly 30,000 square feet (3,000 m2) of exhibit and office space.

[51] As middle-class, white flight from Old West Baltimore continued during the 1960s and 1970s and accelerated after Pennsylvania Avenue was damaged during the civil rights riots, the entire community began a period of long decline.

Minorities of African Americans belong to other religions such as Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, and the Black Hebrew Israelites, while some are atheist or agnostic.

[54] The Orchard Street United Methodist Church is the oldest standing structure built by African Americans in the city of Baltimore.

The church was founded in 1825 by Truman Le Pratt, a West Indian former slave of Governor John Eager Howard.