History of African Americans in Chicago

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable's trading activities in the 1780s.

However, in 1865, the state repealed its "Black Laws" and became the first to ratify the 13th Amendment, partly due to the efforts of John and Mary Jones, a prominent and wealthy activist couple.

By 1879, John W. E. Thomas of Chicago became the first African American elected to the Illinois General Assembly, beginning the longest uninterrupted run of African-American representation in any state legislature in U.S. history.

As White-dominated legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to re-establish White supremacy and create more restrictions in public life, violence against Blacks increased, with lynchings used as extrajudicial enforcement.

At one point in the 1940s, 3,000 African Americans were arriving every week in Chicago—stepping off the trains from the South and making their ways to neighborhoods they had learned about from friends and the Chicago Defender.

At the same time that Blacks moved from the South in the Great Migration, Chicago had recently received hundreds of thousands of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

[13] The Supreme Court of the United States in Shelley v. Kraemer ruled in 1948 that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional, but this did not quickly solve Blacks' problems with finding adequate housing.

After 1945, the early White residents (many Irish immigrants and their descendants) on the South Side began to move away under pressure of new migrants and with newly expanding housing opportunities.

Immigration to Chicago was another pressure of overcrowding, as primarily lower-class newcomers from rural Europe also sought cheap housing and working class jobs.

The White residents did not take to this very well, so city politicians forced the CHA to keep the status quo and develop high rise projects in the Black Belt and on the West Side.

Along the Stroll, a bright-light district on State Street, jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters headlined at nightspots including the Deluxe Cafe.

Prominent writers included Richard Wright (author of Native Son), Willard Motley, William Attaway, Frank Marshall Davis, St. Clair Drake, Horace R. Cayton, Jr., and Margaret Walker.

[35] Muhammad's message appealed to Black Chicagoans of the 1930s and 1940s who were disillusioned with traditional Protestantism and energized by his claim that African Americans would soon be restored to freedom.

Their efforts to build a museum on the west side and continuing to bring awareness to Juneteenth as a national holiday was rewarded with a proclamation in 2011 by Governor Pat Quinn.

[36] Chicago's Black population developed a class structure, composed of a large number of domestic workers and other manual laborers, along with a small, but growing, contingent of middle-and-upper-class business and professional elites.

Fighting job discrimination was a constant battle for African Americans in Chicago, as foremen in various companies restricted the advancement of Black workers, which often kept them from earning higher wages.

Additionally, the African-American market on State Street during this time consisted of barber shops, restaurants, pool rooms, saloons, and beauty salons.

[37] Binga would go on to spearhead an integration campaign on the South Side that put him at odds with the White establishment, with some even attributing the lethal damage of the 1919 race riots in part to the radical aversion to his efforts.

With a growing base and strong leadership in machine politics, Blacks began to win elective office in local and state government.

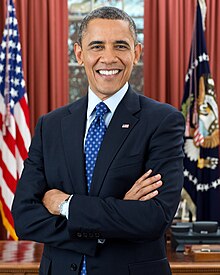

[38] Chicago is home to three of eight African-American United States senators who have served since Reconstruction, who are all Democrats: Carol Moseley Braun (1993–1999), Barack Obama (2005–2008), and Roland Burris (2009–2010).

[42] In the late 19th and early 20th century many prominent African Americans were Chicago residents, including Republican and later Democratic congressman William L. Dawson (America's most powerful Black politician)[4] and boxing champion Joe Louis.

In 1909, tired of poor working conditions, porters for the Pullman Train Company began their first attempts to unionize but encountered heavy opposition.

[47] The magnitude of Black population outflows corresponds strongly with neighborhood homicide rates, with the Austin community area on the city's Far West Side experiencing the largest drop.

Additionally, the widely-criticized closure of 50 CPS schools - primarily in Black neighborhoods - under the mayoral administration of Rahm Emanuel further exacerbated the population spiral.

Many Blacks leaving Chicago are now moving to outlying suburbs, primarily to the south and west of the city in Cook County, or to the east in Northwest Indiana.

[47] Other Black Chicagoans are participating in a "Reverse Great Migration" in search of greater economic opportunities in the U.S. South, including cities such as Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio.

[52] The exodus has been particularly acute in majority-Black neighborhoods: only 35% of predominantly-Black, middle-income census tracts stayed that way in 2017, while 63% fell to low- or moderate-income.

[47] Other redevelopment efforts have focused along the southern lakefront, with the Obama Presidential Center construction bringing jobs - but also potentially gentrification - to the Woodlawn neighborhood.

[53] Notably in Bronzeville, demographers found two of just 193 census tracts nationally that achieved a significant decrease in poverty with minimal displacement of existing populations between 2010 and 2015 - attributed in large part to the abundance of vacant lots which have created opportunities for new construction.

[58] In the 1970s East Africans from Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia formed a small enclave in the Edgewater and Uptown neighborhoods on Chicago's North Side, which has since been enriched by new arrivals from West Africa, including Nigerians and Ghanaians.