History of Ahmedabad

[1][2] In the eleventh century, Karṇa of Caulukya dynasty ruling from Anhilwad Patan (1072–1094) defeated and killed Āśā, the Bhil chieftain of Āśāpallī, near modern Ahmedabad.

[10] Zafar Khan's father Sadharan, were Tāṅks converted to Islam, adopted the name Wajih-ul-Mulk, and had given his sister in marriage to Firuz Shah Tughlaq.

Ahmad Shah I laid the foundation of the city on 26 February 1411[11] (at 1.20 pm, Thursday, the second day of Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year 813[12]) at Manek Burj.

The sage pointed out unique characteristics in the land which nurtured such rare qualities which turned a timid hare to chase a ferocious dog.

Square in form, enclosing an area of about forty-three acres, and containing 162 houses, the Bhadra fort had eight gates, three large, two in the east and one in the south-west corner; three middle-sized, two in the north and one in the south; and two small, in the west.

[15] So the second fortification was carried out by Mahmud Begada in 1486, the grandson of Ahmed Shah, with an outer wall 10 km (6.2 mi) in circumference and consisting of 12 gates, 189 bastions and over 6,000 battlements as described in Mirat-i-Ahmadi.

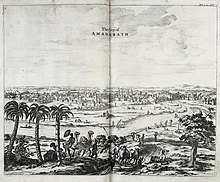

Though Champaner became capital of the sultanate in 1484, Ahmedabad was still greater, very rich and well supplied with many orchards and gardens, walled, and embellished with good streets, squares, and houses.

In the disorders that followed his death, the power of the Gujarat Sultans waned, their revenues fell, and the capital, its trade crippled by Portuguese competition, was impoverished and harassed by the constant quarrels of unruly nobles.

[22] Shortly after (1626), the English traveller Sir Thomas Herbert describes Ahmedabad as "the megapolis of Gujarat, circled by a strong wall with many large and comely streets, shops full of aromatic gums, perfumes and spices, silks, cottons, calicoes and choice Indian and China rarities, owned and sold by the abstemious Banians who here surpass for number the other inhabitants."

In 1695 it was the headquarters of manufactures, 'the greatest city in India, nothing inferior to Venice for rich silks and gold stuffs curiously wrought with birds and flowers.'

Mandelslo, in 1638, describes, its craftsmen as famous for their work in steel, gold, ivory, enamel, mother of pearl, paper, lac, bone, silk, and cotton, and its merchants as dealing in sugar-candy, cumin, honey, lac, opium, cotton, borax, dry and preserved ginger and other sweets, myrobalans, saltpetre and sal ammoniac, diamonds from Bijapur, ambergris, and musk.With the close of Aurangzeb's (1707) reign began a period of disorder.

Under the command of Balaji Vishwanath, the Marathas won over Mughal army in the Panch Mahals, plundered as far as Vatva within five miles of the city, and were only bought off by the payment of £21,000 (Rs.

In 1709 an order came from the new Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I (1707–1712), that in the public prayers, among the attributes of the Khalif Ali, the Shia epithet wasi or heir should be introduced.

Next year (1715) in the city the riots were renewed, shops were plundered and much mischief done, and outside (1716), the Kolis and Kathis grew so bold and presumptuous as to put a stop to trade.

For his services in stopping the pillage of the city Khushalchand, an ancestor of the present Lalbhai family of Ahmedabad, Nagarsheth or chief of the merchants, was raised to that honour.

The revenues cut off, to pay their troops the Mughal officers granting orders on bankers, seized them, put them in prison, and tortured them till they paid.

Though successful against the Marathas the Viceroy had to agree to give them a share of the revenue, and badly off for money had, in 1726, and again in 1730, so greatly to increase taxation that the city rose in revolt.

In the same year (1730) Mubariz-ul-Mulk the Viceroy, superseded by the king Abhai Singh of Jodhpur, refused to give up the city and outside of the walls fought a most closely contested battle.

Under the management of Abhai Singh, Ahmedabad remained unmolested, till in 1733 a Maratha army coming against the city had to be bought off by the payment of a large sum of money.

The Maratha share was the south of the city including the command of the Khan Jahan, Jamalpur, Band or closed, also called Mahudha, Astodiya, and Raipur gates.

For two years Jawan remained in sole power, till in 1752 the Peshwa, owning now the one-half of the Gaekwad's revenues, sent Pandurang Pandit to collect his dues.

And the Marathas unopposed invested the city with their 30,000 horse, the Gaekwad blockading the north, Gopal Hari the east, and the Peshwa's deputy Raghunath Rao watching the south and west.

For more than a year the siege lasted, Momin Khan and his minister Shambhuram a Nagar Brahman, driving back all assaults, and at times dashing out in the most brilliant and destructive sallies.

During the First Anglo–Maratha War (1775–1782), General Thomas Wyndham Goddard, acting in alliance with Fateh Singh Gaekwad against the Pune, with 6,000 troops stormed Bhadra Fort on 12 February 1779.

[29][30] Under the terms of the under the Treaty of Salbai (24 February 1783) Ahmedabad was restored to the Peshwa, the Gaekwad's interest being as before, limited to one-half of the revenue and the command of one of the gates.

A few months later (6 November 1817), it was arranged with the Gaekwad that he should, in payment of a subsidiary force, cede to the British the rights he had obtained under the Peshwa's farm, and, in exchange for territory near Baroda, give up his own share in the city of Ahmedabad.

"The entire discourse of tradition versus modernity, thrown up by exposure to Western literature and culture, was almost non-existent in Ahmedabad," according to literary scholar Svati Joshi.

One visitor, Mary Carpenter, wrote in 1856 after visiting the city, "I found how very far behind Ahmedabad these other places [like Calcutta] were in effort to promote female education among the leading Hindus, in emancipation of the ladies from the thraldom imposed by custom; and in self-effort for improvement on their own part.

By 1960, Ahmedabad had become a metropolis with a population of slightly under half a million people, with classical and colonial European-style buildings lining the city's thoroughfares.

This movement caused the then chief minister of Gujarat, Chimanbhai Patel, to resign and also gave Indira Gandhi one of the excuses for imposing the Emergency on 25 June 1975.