History of American Samoa

Legends suggest that the Tui Manu'a kings ruled a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji, Tonga[1] as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdoms and Polynesian outliers such as Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu.

Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies is well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manu'a dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory "tabua", obsidian and basalt tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus and the egg cowry).

This system of the faamatai and the customs of faasamoa originated with two of the most famous early chiefs of Samoa, who were both women and related, Nafanua and Salamasina.

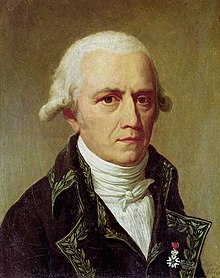

Early Western contact included a battle in the 18th century between French explorers and islanders in Tutuila, for which the Samoans were blamed in the West, giving them a reputation for ferocity.

[2] Whilst, the U.S. Congress had initially been reluctant to establish a formal ties with Samoa, fears that the islands would be lost to Germany and Britain caused a shift in their attitudes.

The perceived inferiority of the Samoan people compared to their white American counterparts was deemed the result of environmental rather than biological factors.

American officials believed that the natural environment of the Samoan islands meant that for generations they had been without hardship and required to complete little work.

Consequently, when Samoan chiefs wrote to President Ulysses S. Grant in 1873 asking him to formally annex Samoa in order to protect their territory from Britain and Germany, this was rejected by Congress.

[3] In the wake of the Spanish-American War (1898), capturing territories like Puerto Rico and the Philippines, U.S. legal actors crafted a novel approach to governing these new possessions.

Initially devised by the Navy and embraced by Congress, this system's legal foundation was later solidified by the Supreme Court's "Insular Cases" (1901–1922).

Scholars describe this shift as a move "from absorbing new territories into the domestic space of the nation to acquiring foreign colonies and protectorates abroad."

Colonial acquisitions were envisioned as eventual states within the Union, while imperial ventures aimed for temporary domination without statehood aspirations.

The Supreme Court's Insular Cases, decided between 1901 and 1922, established a critical precedent: birth in unincorporated U.S. territories wouldn't automatically grant birthright citizenship.

While other territories eventually gained different forms of U.S. citizenship, individuals born in American Samoa currently remain classified as "non-citizen nationals" at birth, lacking automatic U.S.

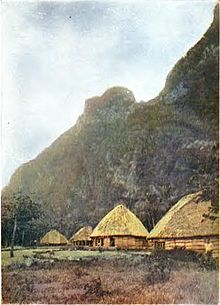

These chiefs' efforts led to the creation of a local legislature, the American Samoa Fono which meets in the village of Fagatogo, the territory's capital.

Although technically considered "unorganized" in that the U.S. Congress has not passed an Organic Act for the territory, American Samoa is self-governing under a constitution that became effective on July 1, 1967.