History of American newspapers

Instead of filling the first part of the Courant with the tedious conventionalities of governors' addresses to provincial legislatures, James Franklin's club wrote essays and satirical letters modeled on The Spectator, which first appeared in London ten years earlier.

[5] When Franklin established himself in Philadelphia, shortly before 1730, the town boasted three "wretched little" news sheets, Andrew Bradford's American Mercury, and Samuel Keimer's Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences and Pennsylvania Gazette.

Although there were forty-three newspapers in the United States when the treaty of peace was signed (1783), as compared with thirty-seven on the date of the battle of Lexington (1775), only a dozen remained in continuous operation between the two events, and most of those had experienced delays and difficulties through lack of paper, type, and patronage.

Mail service, never good, was poorer than ever; foreign newspapers, an important source of information, could be obtained but rarely; many of the ablest writers who had filled the columns with dissertations upon colonial rights and government were now otherwise occupied.

The Salem Gazette printed a full but colored account of the battle of Lexington, giving details of the burning, pillage, and barbarities charged to the British, and praising the militia who were filled with "higher sentiments of humanity."

[15][16] The newspapers of the Revolution were an effective force working towards the unification of sentiment, the awakening of a consciousness of a common purpose, interest, and destiny among the separate colonies, and of a determination to see the war through to a successful issue.

News of events came directly to the editor from Washington's headquarters in nearby Morristown, boosting the morale of the troops and their families, and he conducted lively debates about the efforts for independence with those who opposed and supported the cause he championed.

When Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay united to produce the Federalist Essays, they chose to publish them in The Independent Journal and The Daily Advertiser, from which they were copied by practically every paper in America long before they were made into a book.

To offset the influence of this, Jefferson and Madison induced Philip Freneau, who had been editing The Daily Advertiser in New York, to set up a "half weekly", to "go through the states and furnish a Whig [Republican] vehicle of intelligence."

Fellow Federalist Cobbett labeled him "a traitor to the cause of Federalism", calling him "a toad in the service of sans-culottism", "a prostitute wretch", "a great fool, and a barefaced liar", "a spiteful viper", and "a maniacal pedant."

Chief of these was Cobbett, whose control of abusive epithet and invective may be judged from the following terms applied by him to his political foes, the Jacobins: "refuse of nations"; "yelper of the Democratic kennels"; "vile old wretch"; "tool of a baboon"; "frog-eating, man-eating, blood-drinking cannibals"; "I say, beware, ye under-strapping cut-throats who walk in rags and sleep amidst filth and vermin; for if once the halter gets round your flea-bitten necks, howling and confessing will come too late."

He wrote of the "base and hellish calumnies" propagated by the Jacobins, and of "tearing the mask from the artful and ferocious villains who, owing to the infatuation of the poor, and the supineness of the rich, have made such fearful progress in the destruction of all that is amiable and good and sacred among men."

The power wielded by these anti-administration editors impressed John Adams, who in 1801 wrote: "If we had been blessed with common sense, we should not have been overthrown by Philip Freneau, Duane, Callender, Cooper, and Lyon, or their great patron and protector.

Fenno's Gazette had served the purpose for Washington and Adams; but the first great example of the type was the National Intelligencer established in October 1800, by Samuel Harrison Smith, to support the administration of Jefferson and of successive presidents until after Jackson it was thrown into the opposition, and The United States Telegraph, edited by Duff Green, became the official paper.

It was replaced at the close of 1830 by a new paper, The Globe, under the editorship of Francis P. Blair, one of the ablest of all ante-bellum political editors, who, with John P. Rives, conducted it until the changing standards and conditions in journalism rendered the administration organ obsolescent.

Neither the Union nor its successors, which maintained the semblance of official support until 1860, ever occupied the commanding position held by the Telegraph and The Globe, but for forty years the administration organs had been the leaders when political journalism was dominant.

Though it could still be said that "too many of our gazettes are in the hands of persons destitute at once of the urbanity of gentlemen, the information of scholars, and the principles of virtue", a fact due largely to the intensity of party spirit, the profession was by no means without editors who exhibited all these qualities, and put them into American journalism.

Under the influence of Thomas Ritchie, vigorous and unsparing political editor but always a gentleman, who presided at the first meeting of Virginia journalists, the newspaper men in one state after another resolved to "abandon the infamous practice of pampering the vilest of appetites by violating the sanctity of private life, and indulging in gross personalities and indecorous language", and to "conduct all controversies between themselves with decency, decorum, and moderation."

Of the others named, and many besides, it could be said with approximate truth that their ideal was "a full presentation and a liberal discussion of all questions of public concernment, from an entirely independent position, and a faithful and impartial exhibition of all movements of interest at home and abroad."

In editing the New Yorker Greeley had acquired experience in literary journalism and in political news; his Jeffersonian and Log Cabin, were popular Whig campaign papers, had brought him into contact with politicians and made his reputation as an insightful, vigorous journalist.

In conformity with these principles Greeley lent his support to all proposals for ameliorating the condition of the labouring men by industrial education, by improved methods of farming, or even by such radical means as the socialistic Fourier Association.

Taking The Times of London as his model, he tried to combine in his paper the English standard of trustworthiness, stability, inclusiveness, and exclusiveness, with the energy and news initiative of the best American journalism; to preserve in it an integrity of motive and a decorum of conduct such as he possessed as a gentleman.

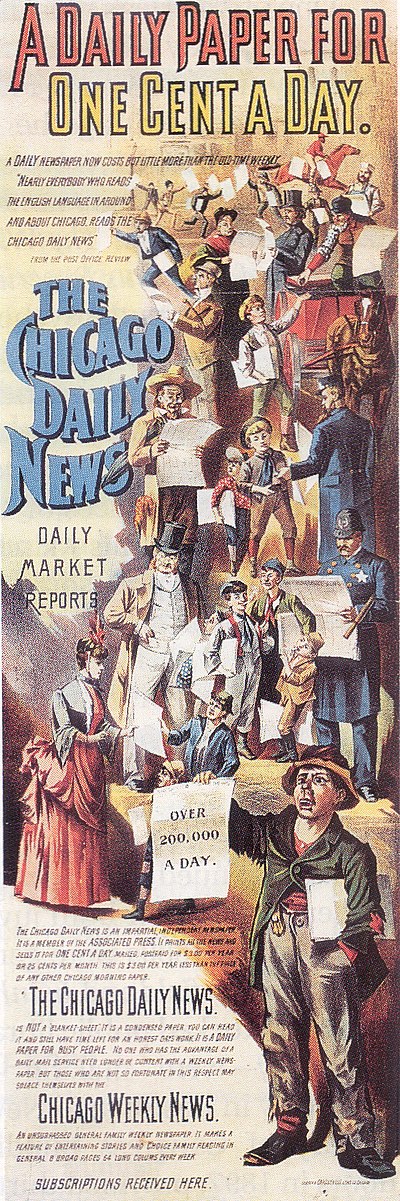

Western cities, developed influential newspapers of their own in Chicago, San Francisco and St. Louis; the Southern press went into eclipse as the region lost its political influence and talented young journalists headed North for their careers.

The Associated Press became increasingly important and efficient, producing a vast quantity of reasonably accurate, factual reporting on state and national events that editors used to service the escalating demand for news.

Both were Democratic, both were sympathetic to labor and immigrants (a sharp contrast to publishers like the New York Tribune's Whitelaw Reid, who blamed their poverty on moral defects), and both invested enormous resources in their Sunday publications, which functioned like weekly magazines, going beyond the normal scope of daily journalism.

The island was in a terrible economic depression, and Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, sent to crush the rebellion, herded Cuban peasants into concentration camps and caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

He later campaigned for his party's presidential nomination, but lost much of his personal prestige when columnist Ambrose Bierce and editor Arthur Brisbane published separate columns months apart that called for the assassination of McKinley.

In Thomas Harris' novel Red Dragon, from the Hannibal Lecter series, a sleazy yellow journalist named Freddy Lounds, who writes for the National Tattler tabloid, is tortured and set aflame for penning a negative article about serial killer Francis Dolarhyde.

[97][98] E. W. Scripps founder of the first national newspaper chain in the United States, sought in the early years of the 20th century to create syndicated services based on product differentiation while appealing to the needs of his readers.

Diario La Estrella began in 1994 as a dual-language insert of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and first grew into an all-Spanish stand-alone paper with a twice-weekly total circulation of 75,000 copies distributed free via newsstands and selective home delivery.

Top row: The Union and Advertiser (William Purcell) - The Omaha Daily Bee ( Edward Rosewater ) - The Boston Daily Globe ( Charles H. Taylor ) - Boston Morning Journal (William Warland Clapp) - The Kansas City Times (Morrison Mumford) - The Pittsburgh Dispatch ( M. O'Neill ).

Middle row: Albany Evening Journal (John A. Sleicher) - The Milwaukee Sentinel (Horace Rublee) - The Philadelphia Record (William M. Singerly) - The New York Times ( George Jones ) - The Philadelphia Press ( Charles Emory Smith ) - The Daily Inter Ocean ( William Penn Nixon ) - The News and Courier (Francis Warrington Dawson).

Bottom row: Buffalo Express (James Newson Matthews) - The Daily Pioneer Press (Joseph A. Wheelock) - The Atlanta Constitution ( Henry W. Grady & Evan Howell ) - San Francisco Chronicle ( Michael H. de Young ) - The Washington Post ( Stilson Hutchins )