History of Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Human habitation in the Baton Rouge area has been dated to about 8000 BC based on evidence found along the Mississippi, Comite, and Amite rivers.

Many were transported to France and subsequently resettled in southern Louisiana (New Spain); they settled in an area west and south of Baton Rouge that would come to be known as Acadiana.

They maintained a separate culture from that of later Anglo-American Southern Baptist settlers, continuing their traditions of distinct clothing, music, food, and Catholic faith.

That year, the Spanish Governor Don Bernardo de Gálvez led a militia of nearly 1,400 soldiers and a small contingent of rebellious English-speaking colonials from New Orleans toward Baton Rouge.

A colony of Pennsylvania German farmers migrated north from Bayou Manchac, after a series of floods in the 1780s, and settled to the south of Baton Rouge.

As a result of the United States' 1803 Louisiana Purchase, it gained the former French territory in North America (retroceded by Spain to France).

In 1825, Baton Rouge was visited by the Marquis de Lafayette, French hero of the American Revolution, as part of his triumphal tour of the United States.

In 1849, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans, dominated in number by wealthy rural planters, decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge.

The majority of representatives feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city and the continuing strong influence of French Creoles in politics.

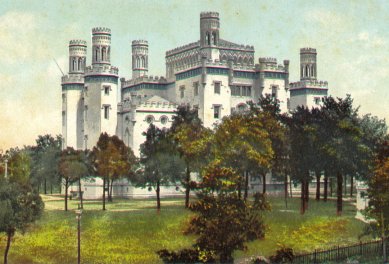

[9] But the riverboat pilot and writer Mark Twain loathed the sight; later in his Life on the Mississippi (1874), he wrote, "It is pathetic ... that a whitewashed castle, with turrets and things ... should ever have been built in this otherwise honorable place.

However, Baton Rouge escaped the extreme devastation faced by cities that were major conflict points during the Civil War, and it still has many structures that predate it.

They moved out of rural areas to escape white control and to seek jobs and education more available in towns, as well as the safety of being in their own communities.

Following a disputed gubernatorial election in 1872, in 1874 thousands of paramilitary White League members took over state government buildings in New Orleans for several days.

Before the end of Reconstruction, signified by the withdrawal of Federal troops in 1877, the white Democratic Party politicians regained control of the state's and the city's political institutions.

In 1886, a statue of a Confederate soldier was dedicated at the corner of Third Street and North Boulevard, in honor of those who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In the early 21st century, the statue was removed to enable construction, beginning in 2010, of the North Boulevard Town Square, located directly behind the Old Louisiana State Capitol.

[citation needed] Increased civic-mindedness and the arrival of the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway stimulated investments in the local economy, attracted new businesses, and led to the development of more forward-looking leadership.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Baton Rouge was being industrialized due to its strategic location for the production of petroleum, natural gas, and salt.

In 1932, during the Great Depression, Governor Huey P. Long directed the construction of a new Louisiana State Capitol, a public works project that was also a symbol of modernization.

Throughout World War II, military demand for increased production at local chemical plants contributed to the growth of the city, generating many new defense jobs.

On June 20, 1953 black citizens of Baton Rouge began an organized boycott of the segregated municipal bus system that lasted for eight days.

[12] The boycott was led by the newly formed United Defense League (UDL), under the direction of Willis Reed, later publisher of the Baton Rouge newspaper; Reverend T. J. Jemison and Raymond Scott.

A volunteer "free ride" system, coordinated through black churches, supported the efforts and helped provide transportation for African Americans.

In the view of many historians, the boycott's success in getting justice for black bus riders led the way for larger organized efforts within the civil rights movement.

Major Johns and the 16 students arrested for sitting-in were expelled from SU and barred from all public colleges and universities in the state, threatening their education and future livelihoods.

[14] In October 1961, SU students Ronnie Moore, Weldon Rougeau and Patricia Tate revived the Baton Rouge CORE chapter.

After negotiations with downtown merchants failed to end segregation in retail stores, they called for a consumer boycott in early December, at the start of the busy holiday shopping season.

Judge West's order was finally overturned by a higher court in 1964, but during the intervening years, civil rights activity was effectively suppressed.

SNCC Chairman Chuck McDew and white field secretary Bob Zellner were also arrested and charged with "criminal anarchy" when they visited Diamond in jail.

By the end of the 2000s decade, Baton Rouge was one of the largest mid-sized American business cities and one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas with populations under 1 million — with 633,261 residents in 2000 and an estimated 750,000 in 2008.