History of Carmona, Spain

The history of Carmona begins at one of the oldest urban sites in Europe, with nearly five thousand years of continuous occupation on a plateau rising above the vega (plain) of the River Corbones in Andalusia, Spain.

[8] In the second half of the 1st century, with the social stability brought by the Pax Romana, Carmo became a crossroads on the Via Augusta and an important outpost of the Roman empire (the highway, by then called El Arrecife, was still used in the Middle Ages; a few remnants of some sections and a bridge have survived).

At the end of the 3rd century, Carmona entered a gradual decline, which led eventually to: the dismantling of public and religious buildings, a general contraction of the urban area, the depopulation of nearby villages, and the abandonment of large landed properties.

[15] The Andalucista politician, writer, and historian Blas Infante, known as the father of Andalusian nationalism (Padre de la Patria Andaluza),[16] was seized and summarily executed 11 August 1936 by Franco's forces on the Seville road to Carmona at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

[19] The practice of cooperative agriculture led to higher crop yields and consequent population growth, putting pressure on resource areas required to produce food and necessitating their defense.

Agriculture started in the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods and became widespread by the early third millennium BC, resulting in intensive colonisation of the land suitable for farming in the Los Alcores and La Campiña regions of what is now the province of Seville.

[22] The first settlement within the limits of present-day Carmona rose about 4500 years ago and spread across the plateau, the people preferring to occupy the higher elevations and slopes of the hills that dominate the fertile plain of the Corbones and the terraces that descend gradually to the Guadalquivir.

Excavations in a building plot on the street Calle Dolores Quintanilla have yielded some information about the earliest history of Carmona; apparently the town was formed by the merger of hut houses and granaries.

[32] The population of this proto-urban core built defences with walls of sloping masonry on its western flank, the most vulnerable, and continued to consolidate until the mid-6th century BC, when the Tyrian Phoenician trade network disintegrated.

A period of economic prosperity based on agricultural production and long-distance trade began,[36] as evidenced by the findings of amphorae from Andalusia in the Monte Testaccio of Rome, and by the volume of Gallic ceramics documented in local excavations.

Julius Caesar famously wrote in his "Commentary on the Civil War" (Commentarii de bello civili): "Carmonenses, quae est longe firmissima totius provinciae civitas" (Carmona is by far the strongest city of the province).

In the "Arbollón" (a natural stream bed at the northeast foot of the hill where the original oppidum lay)[42] section of the city, an archaeological excavation conducted in 1989 documented the existence of a valley that had silted in during the Roman period, in the latter 1st century.

In the bastion of the stronghold, major Roman additions included the construction of a curtain wall, or facing, called a cortina, which augmented the structure's height, and a temple built in the second half of the 1st century BC of which the only remains are the podium on which it stood.

In 1881 George Bonsor and Juan Fernández López purchased two plots of land containing old quarries and olive groves, situated a short distance west of Carmona, and commenced excavations.

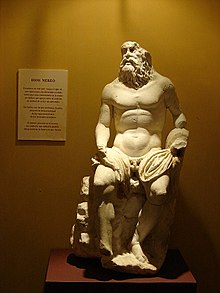

During the course of the excavations, numerous objects of interest were found, amounting to over 3,000 in number, among which are many inscriptions, fragments of statues, glass, marble, and earthenware urns, lamps and mirrors, rings and coins, and other valuable articles, all of which have been placed in a museum in the town specially arranged for them.

George Bonsor also recovered a large variety of materials at the necropolis of the La Cruz del Negro, including engraved scarabs, ivory combs, lamps, vases and burnished handmade bowls.

Enclosed in subterranean chambers hewn from the living rock, the tombs are often frescoed and contain columbarium niches in which many of the limestone funerary urns remain intact; these are frequently inscribed in Latin with the name of the deceased.

These agreements enabled the coexistence of the peoples of the occupied cities, allowing their residents to maintain their own laws and institutions, retain their property and practice their religion, in return for payment of a tax called the jizya (Arabic: جزية ǧizyah).

There is little specific ethnographic information to define the political situation of Qarmūnâ in this period, although there are historical references to the presence of members of the Masmuda and Sanhaja Berber tribes and of people of Arab origin.

Excavations provide limited data, since the only items that appear recurrently are cesspools with their waste residues; the walls and floors revealed by ancillary archaeological techniques under the modern city have been Roman.

The Mosque was built in the 11th century, occupying the site where the church of Santa María stands now, Some of the original Islamic structure survives in the Patio de los Naranjos, a large courtyard whose typological elements date it to the period.

The varied picture presented by an approach to the historic centre of modern Carmona suggests its urban appearance during the Islamic period, with the exception that at that time there were many more vacant plots of land, especially in the area closest to the wall.

The city was granted a charter (fuero) as a municipality to regulate its governance, and designated by the king a señorío de realengo (royal manor), making him its lord and placing it under his direct administration.

The picture that emerges from analysis of the population distribution of Carmona in this period is of a society with a Muslim majority dominated by a minority of Christians (mainly Castilian-Leonese and to a lesser extent, Aragonese and Navarrese), who controlled the administrative bodies and governmental institutions.

The end of the city's municipal autonomy marked the firm establishment of the system of Corregidores (magistrates), these officials being appointed directly by the Crown, and in whose hands lay the reins of local power.

By the turn of the century, the suburb of San Pedro had grown sufficiently to accommodate a range of services not offered at the Plaza de Arriba, from a brothel to coach inns and taverns, as well as businesses of all kinds, strategically placed along the roadway to the city.

A great part of the fortress was destroyed in the earthquakes of 1504 and 1755, leaving only the gate and three of the towers, The parador Alcázar del rey Don Pedro is a modern state-run upscale hotel built on the site.

The reign of the Habsburg kings of Spain posed an ongoing challenge for Carmona to meet the demands for men and money made by the royal Court, which was perpetually involved in military conflicts.

[71] During the Peninsular war, the city's horsemen participated in the decisive Battle of Bailén, helping to fight back Napoleon's elite Imperial Dragoons commanded by General Dupont in the first major defeat of the Grande Armée on 16–19 July 1808.

The disentailment of Church property allowed the city to take advantage of the huge space occupied by the now empty convent of Santa Catalina, giving Carmona its first stable market location, the Plaza del Mercado de Abastos.