History of Frankfurt

[citation needed] Frankfurt is located in what was originally a swampy portion of the Main valley, a lowland criss-crossed by channels of the river.

The Odenwald and Spessart ranges surrounded the area, lending a defensive advantage, and placenames show that the lowlands on both sides of the river were originally wooded.

In 794 a letter from the Emperor to the bishop of Toledo contained "in loco celebri, qui dicitur Franconofurd", which reads "that famous place, which is called Frankfurt."

Louis the Pious, Charlemagne's son, selected Frankfurt as his seat, extended the palatinate, built a larger palace, and in 838 had the city encircled by defensive walls and ditches.

After the Treaty of Verdun (843), Frankfurt became to all intents and purposes the capital of East Francia and was named Principalis sedes regni orientalis (principal seat of the eastern realm).

Also, as the Holy Roman Emperor had no permanent residence anymore, Frankfurt remained the center of imperial power and the principal city of Eastern Francia.

After the era of lesser importance under the Salian and Saxon emperors, a single event once again brought Frankfurt to the fore: it was in the local church in 1147 that Bernard of Clairvaux called, amongst others, the Hohenstaufen king Conrad III to the Second Crusade.

In 1612, following the election of Emperor Matthias, the council rejected the Guild's request, to read out publicly the imperial privileges given to the city.

Frankfurt's status as a free city ended when it was granted to Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg in the same year.

When in 1831 Arthur Schopenhauer, a lecturer at the time, moved from Berlin to Frankfurt, he justified it with the lines: "Healthy climate, beautiful surroundings, the amenities of large cities, the Natural History Museum, better theater, opera, and concerts, more Englishman, better coffee houses, no bad water… and a better dentist."

Frankfurt was annexed by Prussia as a result of the war, and the city was made part of the province of Hesse-Nassau.In 1933 the Jewish mayor (Oberbürgermeister) Ludwig Landmann was replaced by NSDAP member Friedrich Krebs.

Their property and valuables were stolen by the Gestapo before deportation, and most were subjected to extreme violence and sadism during transport to the train stations for the cattle wagons which carried them east.

The US 5th Infantry Division seized the Rhine-Main airport on 26 March 1945 and crossed assault forces over the river into the city on the following day.

The tanks of the supporting US 6th Armored Division at the Main River bridgehead came under concentrated fire from dug-in heavy flak guns at Frankfurt.

The urban battle consisted of slow clearing operations on a block-by-block basis until 29 March 1945, when Frankfurt was declared as secured, although some sporadic fighting continued until 4 April 1945.

To remove and recycle the rubble the city authorities in the autumn of 1945 created in partnership with the Metallgesellschaft industrial group and the Philipp Holzmann and Wayss & Freytag construction companies the Trümmerverwertungsgesellschaft.

Once the rubble was removed from the damaged areas post-war reconstruction of the city took place in a sometimes simple modern style, thus changing Frankfurt's architectural face.

A few significant historical landmark buildings were reconstructed, albeit in a simplified manner (e.g. St. Paul's Church (which was the first rebuilt), Goethe House) and Römer.

The emperor, however, attempted to exact still more money from the Jews, and it was only thanks to the resistance of the city that King Adolf did not succeed in 1292 in extracting from them the sum required for his coronation.

At the beginning of these outbreaks the circumspect Emperor Charles IV, who feared for his income, pledged the Jews to the city for more than 15,000 pounds of hellers, stipulating that he would redeem them, which he never did.

In 1525 the impending danger of expulsion was averted by the municipal council; but the Jews were restricted in their commerce and were forbidden to build their houses higher than three stories.

The importance and status of the community at the beginning of the eighteenth century are indicated by the gracious reception accorded to the deputation that offered presents to Joseph I on his visit to Heidelberg in 1702.

In 1756 the Jews received permission to leave their street in urgent cases on Sundays and feast days for the purpose of fetching a physician or a barber or mailing a letter, but they were required to return by the shortest way.

Although he lost his case, proceedings were several times renewed with the aid of King Frederick I of Prussia, and only in 1773 was the community finally released from all claims brought by Eisenmenger's heirs.

When Frankfurt was besieged during the interregnum in 1552, a garrison with cannon was stationed in the cemetery, and an attempt was even made to force the Jews to sink the tombstones and to level the ground; but against this they protested successfully (July 15, 1552).

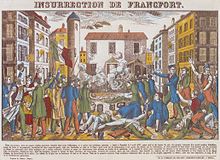

During the Fettmilch riots the whole community spent the night of September 1, 1614, in the cemetery, prepared for death, and thought themselves fortunate when they were permitted to leave the city through the Fischerfeld gate on the following afternoon.

The fire station existed down to 1882; the site of the ovens is now covered by the handsome building of the Sick Fund, and that of the Holzplatz and the garden by the Philanthropin schoolhouse.

Owing to this restriction, the printing requirements of Frankfurt were in large measure met by Jewish presses established in neighboring towns and villages, such as Hanau, Homburg, Offenbach, and Rödelheim, the last-named place being specially notable.

From the year 1677 till the beginning of the eighteenth century there were two Christian printing establishments in Frankfurt at which Hebrew books were printed: (1) The press owned till 1694 by Balthasar Christian Wust, who began with David Clodius' Hebrew Bible; his last work was the unvocalized Bible prepared by Eisenmenger, 1694; up to 1707 the press was continued by John Wust.

Andrea (1716), Nicolas Weinmann (1709), Antony Heinscheit (1711–19), and, above all, John Kölner, who during the twenty years of his activity (1708–27) furnished half of the Hebrew works printed at Frankfurt up to the middle of the nineteenth century.