History of Greenland

During this time, Denmark-Norway, apparently believing the Norse settlements had survived, continued to claim sovereignty over the island despite the lack of any contact between the Norsemen (specially Icelanders) installed in Greenland and their Scandinavian brethren.

(The population of those islands are thought to have descended, in turn, from inhabitants of Siberia who migrated into North America through Beringia thousands of years ago.)

According to the sagas, in the year 1000 Erik's son, Leif Erikson, left the settlement to explore the regions around Vinland, which historians generally assume to have been located in present-day Newfoundland.

[12] If the presumption is true then the Norse probably cleared the landscape by felling trees to use as building material and fuel, and by allowing their sheep and goats to graze there in both summer and winter.

Farmers kept cattle, sheep and goats - shipped into the island - for their milk, cheese and butter, while most of the consumed meat came from hunted caribou and seals.

[14] The Greenland settlements carried on a trade with Europe in ivory from walrus tusks, as well as exporting rope, sheep, seals, wool and cattle hides (according to one 13th-century account).

Seaver believes that the Greenlanders cannot have starved to death, but rather may have been wiped out by Inuit or unrecorded European attacks, or they may have abandoned the colony for Iceland or Vinland.

[46] The Greenlanders' main commodity was the walrus tusk,[28] which was used primarily in Europe as a substitute for elephant ivory for art décor, whose trade had been blocked by conflict with the Islamic world.

[50] In the 1540s,[11] a ship drifted off-course to Greenland and discovered the body of a dead man lying face down who demonstrated cultural traits of both Norse and Inuit.

Around 1514, the Norwegian archbishop Erik Valkendorf (Danish by birth, and still loyal to Christian II) planned an expedition to Greenland, which he believed to be part of a continuous northern landmass leading to the New World with all its wealth, and which he fully expected still to have a Norse population, whose members could be pressed anew to the bosom of church and crown after an interval of well over a hundred years.

Most archaeologists reject any decisive judgment based on this one fact, however, as fish bones decompose more quickly than other remains, and may have been disposed of in a different manner.

[11] This story is thus regarded as a myth that is not based on true events, because archeological excavations of the farm revealed no evidence of fire or human conflict.

[57] In the region of this culture, there is archaeological evidence of gathering sites for around four to thirty families, living together for a short time during their movement cycle.

[58] These people, the ancestors of the modern Greenland Inuit,[57][59] were flexible and engaged in the hunting of almost all animals on land and in the ocean, including walrus, narwhal, and seal.

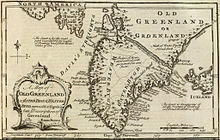

[62] The precise date of rediscovery is uncertain because south-drifting icebergs during the Little Ice Age long made the eastern coast unreachable.

Christian I of Denmark purportedly sent an expedition to the region under Pothorst and Pining to Greenland in 1472 or 1473; Henry VII of England sent another under Cabot in 1497 and 1498; Manuel I of Portugal sent a third under Corte-Real in 1500 and 1501.

[62] The island was "rediscovered" yet again by Martin Frobisher in 1578, prompting King Frederick II of Denmark to outfit a new expedition of his own the next year under the Englishman James Alday; this proved a costly failure.

In the second half of the 17th century Dutch, German, French, Basque, and Dano-Norwegian ships hunted bowhead whales in the pack ice off the east coast of Greenland, regularly coming to shore to trade and replenish drinking water.

From 1711 to 1721,[64] the Norwegian cleric Hans Egede petitioned King Frederick IV of Denmark for funding to travel to Greenland and re-establish contact with the Norse settlers there.

[65] Frederick permitted Egede and some Norwegian merchants to establish the Bergen Greenland Company to revive trade with the island but refused to grant them a monopoly over it for fear of antagonizing Dutch whalers in the area.

An attempt to found a royal colony under Major Claus Paarss established the settlement of Godthåb ("Good Hope") in 1728, but became a costly debacle which saw most of the soldiers mutiny[65] and the settlers killed by scurvy.

Around the same time, the merchant Jacob Severin took over administration of the colony and its trade, and having secured a large royal stipend and full monopoly from the king, successfully repulsed the Dutch in a series of skirmishes in 1738 and 1739.

However, though kale, lettuce, and other herbs were successfully introduced, repeated attempts to cultivate wheat or clover failed throughout Greenland, limiting the ability to raise European livestock.

The 19th century saw increased interest in the region on the part of polar explorers and scientists like William Scoresby and Greenland-born Knud Rasmussen.

The collapse of the cod fisheries and mines in the late 1980s and early 1990s greatly damaged the economy, which now principally depends on Danish aid and cold-water shrimp exports.

Large sectors of the economy remain controlled by state-owned corporations, with Air Greenland and the Arctic Umiaq ferry heavily subsidised to provide access to remote settlements.

Fears that the customs union would allow foreign firms to compete and overfish its waters were quickly realised and the local parties began to push strongly for increased autonomy.

Following a successful referendum on self-government in 2008, the local parliament's powers were expanded and Danish was removed as an official language in 2009. International relations are now largely, but not entirely, also left to the discretion of the home rule government.

The US military bases on the island remain a major issue, with some politicians pushing for renegotiation of the 1951 US–Denmark treaty by the Home Rule government.

The 1999–2003 Commission on Self-Governance even proposed that Greenland should aim at Thule base's removal from American authority and operation under the aegis of the United Nations.

1. From 700 to 750 people belonging to the Late Dorset Culture move into the area around Smith Sound, Ellesmere Island and Greenland north of Thule.

2. Norse settlement of Iceland starts in the second half of the 9th century.

3. Norse settlement of Greenland starts just before the year 1000.

4. Thule Inuit move into northern Greenland in the 12th century.

5. Late Dorset culture disappears from Greenland in the second half of the 13th century.

6. The Western Settlement disappears in mid 14th century.

7. In 1408 is the Marriage in Hvalsey, the last known written document on the Norse in Greenland.

8. The Eastern Settlement disappears in mid 15th century.

9. John Cabot is the first European in the post-Iceland era to visit Labrador - Newfoundland in 1497.

10. "Little Ice Age" from c. 1600 to mid 18th century.

11. The Norwegian priest Hans Egede arrives in Greenland in 1721.