History of Lviv

Lviv (Ukrainian: Львівⓘ, L’viv; Polish: Lwów; German: Lemberg or Leopoldstadt[citation needed] (archaic); Yiddish: לעמבערג; Russian: Львов, romanized: Lvov, see also other names) is an administrative center in western Ukraine with more than a millennium of history as a settlement, and over seven centuries as a city.

Prior to the creation of the modern state of Ukraine, Lviv had been part of numerous states and empires, including, under the name Lwów, Poland and later the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; under the name Lemberg,[1] the Austrian and later Austro-Hungarian Empires; the short-lived West Ukrainian People's Republic after World War I; Poland again; and the Soviet Union.

Lviv was officially founded in 1256 by King Daniel of Galicia in the Ruthenian principality of Halych-Volhynia and named in honour of his son Lev.

The city was inherited by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1340 and ruled by voivode Dmytro Dedko, the favourite of the Lithuanian prince Lubart, until 1349.

[14] After Boleslaus Yuriy of Masovia and Halych death in 1340, the rights to his domain were passed to his fellow Piast dynast and cousin, King Casimir III of Poland.

The local nobles elected one of their own, Dmytro Dedko, as ruler, and repulsed a Polish invasion during the wars over the succession of Galicia-Volhynia Principality when King Casimir III undertook an expedition to conquer Lviv in 1340, burning down the old princely castle.

After Casimir had died in 1370, he was succeeded by his nephew, King Louis I of Hungary, who in 1372 put Lviv together with the region of Galicia-Volhynia under the administration of his relative Władysław, Duke of Opole.

The city was granted the right of transit and started to gain significant profit from the goods transported between the Black Sea and the Baltic.

In 1675 the city was attacked by the Ottomans and the Tatars, but King John III Sobieski defeated them on August 24 in what is called the Battle of Lwów.

In 1772, following the First Partition of Poland, the city was annexed by Austria and became the capital of the Austrian province called the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria as Lemberg, its Germanic name.

In order to educate a new generation of Greek Catholic priests, the university established the Ruthenian Scientific Institute for non-Latin speaking students in 1787.

Physician Franz Masoch and his assistant Peter Krausnecker made significant contributions to the development of vaccination and the fight against Smallpox.

Early in the 19th century the city became the new seat of the primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the Archbishop of Kyiv (Kiev), Halych and Rus, the Metropolitan of Lviv.

In the 19th century, blaming the Polish nobility for the backwardness of the region,[20] the Austrian administration attempted to Germanise the city's educational and governmental functions.

After repeated violations, Hammerstein ordered the arrest of the officers, and this caused the National Guards to seize the town center and throw up barricades.

[21] On 6 November 1848, the Imperial Austrian Army under the command of General Hammerstein commenced bombardment of the city center for three hours, setting fire to the town hall (Rathaus), as well as the academy building, library, museum, and many streets lined with houses.

Most of the pleas were accepted twenty years later in 1861: a Galician parliament (Sejm Krajowy) was opened and in 1867 Galicia was granted vast autonomy, both cultural and economic.

In 1853, it was the first European city to have street lights due to innovations discovered by Lviv inhabitants Ignacy Łukasiewicz and Jan Zeh.

From 1873, Galicia was de facto an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary with Polish and, to a much lesser degree, Ukrainian or Ruthenian, as official languages.

Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm and provincial administration, both established in Lviv, had extensive privileges and prerogatives, especially in education, culture, and local affairs.

Many Belle Époque public edifices and tenement houses were erected, and buildings from the Austrian period, such as the opera theater built in the Viennese neo-Renaissance style, still dominate and characterize much of the centre of the city.

[39] Depolonisation combined with large scale anti-Polish actions began immediately, with huge numbers of Poles and Jews from Lviv deported eastward into the Soviet Union.

After being subject to deadly pogroms, the Jewish inhabitants of the area were rushed into a newly created ghetto and then mostly sent to various German concentration camps.

Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed in Lviv the Government of an independent that "will work closely with the National-Socialist Greater Germany, under the leadership of its leader Adolf Hitler, which is forming a new order in Europe and the world" – as stated in the text of the "Act of Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood".

The Lwów Ghetto was established after the pogroms, holding around 120,000 Jews, most of whom were deported to the Belzec extermination camp or killed locally during the following two years.

A large effort in saving the members of the Jewish community was organized by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky.

Although U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to allow Poland to keep Lviv, he and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill reluctantly agreed.

With Russification being a general Soviet policy in post-war Ukraine, in Lviv it was combined with the disestablishment of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (see History of Christianity in Ukraine) at the state-sponsored Synod of Lviv, which agreed to transfer all parishes to the recently recreated Ukrainian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Today the city remains one of the most important centers of Ukrainian cultural, economic and political life and is noted for its beautiful and diverse architecture.

In its recent history, Lviv strongly supported Viktor Yushchenko during the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election and played a key role in the Orange Revolution.

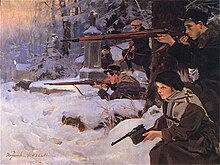

A painting depicting Polish youths in the Lwów Uprising by Poles against the West Ukrainian People's Republic proclaimed in the city.