History of Malawi

Human remains at a site dated about 8000 BCE showed physical characteristics similar to peoples living today in the Horn of Africa.

[citation needed] According to Chewa myth, the first people in the area were a race of dwarf archers which they called Akafula or Akaombwe.

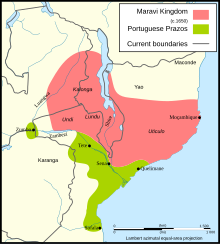

The Amaravi, who eventually became known as the Chewa (a word possibly derived from a term meaning "foreigner"), migrated to Malawi from the region of the modern-day Republic of Congo to escape unrest and disease.

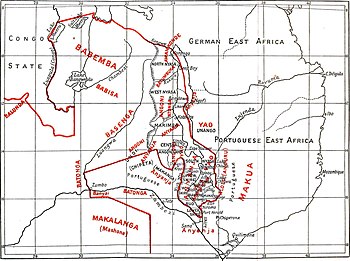

In the 19th century, the Angoni or Ngoni people and their chief Zwangendaba arrived from the Natal region of modern-day South Africa.

Staging from rocky areas, the Ngoni impis would raid the Chewa (also called Achewa) and plunder food, oxen and women.

They came to Malawi from northern Mozambique either to escape from conflict with the Makuwa, who had become their enemies, or to profit from the slave and ivory trades with the Arabs from Zanzibar, the Portuguese, and the French.

By the time, David Livingstone encountered them on his travels, recording their practice of slavery, they traded with the Rwozi of Zimbabwe, with the Bisa on the Luangwa river in modern-day Zambia, and even the Congo and the eastern coast.

Craftsmen built dhows for lake travel, farmers set out irrigation for the growing of rice, and prominent members of society founded madrassahs and boarding schools.

The Yao were the first, and for a long while, the only group to use firearms, which they bought from Europeans and Arabs, in conflicts with other tribes, including the Makololo who had migrated from Southern Africa after being displaced by the Zulu people.

Jumbe (Salim Abdallah) followed the Yao trade route from the eastern side of Lake Malawi up to Nkhotakota.

The Lomwe came from a hill in Mozambique called uLomwe, north of the Zambezi River and south east of Lake Chilwa in Malawi.

[7] To escape from ill-treatment, the Lomwe headed north and entered Nyasaland by way of the southern tip of lake Chilwa, settling in the Phalombe and Mulanje areas.

[8] More group of missionaries arrived in 1875-6 from the Free Church of Scotland, and established a base at Cape Maclear at the southern end of Lake Malawi.

Laws, who quickly gained fame for his medical expertise, decided to establish missions further north, at Bandawe among the Tonga and at Kaningina among the Ngoni people.

There, the missionaries found fertile ground in a turbulent political climate: the missions became buffer zones for the Tonga, who were near-constantly under attack by Ngoni raiders.

Others soon followed: traders, hunters, planters came, and even missionaries from different denominations; from 1889, the Catholic White Fathers attempted to convert the Yao.

Today, fewer Yao are found in jobs requiring literacy, which has forced a large number of them to migrate to South Africa as a source of labour.

The Yao believe that they have been deliberately marginalized by the authorities because of their faith; in Malawi, they are predominantly farmers, tailors, guards, fishermen or working in other unskilled manual jobs.

At one time, a number of Yao concealed their names in order to progress in education: Mariam was known as Mary; Yusufu was called Joseph; Che Sigele became Jeanet.

Chilembwe opposed both the recruitment of Nyasas as porters in the East African campaign of World War I, as well as the system of colonial rule.

In a second constitutional conference in London in November 1962, the British Government agreed to give Nyasaland self-governing status the following year.

Hastings Banda became Prime Minister on 1 February 1963, although the British still controlled the country's financial, security, and judicial systems.

The reasons that the ex-ministers put forward for the confrontation and their subsequent resignations were the autocratic attitude of Banda, who failed to consult other ministers and kept power in his own hands, his insistence on maintaining diplomatic relations with South Africa and Portugal and a number of domestic austerity measures.

Several of the former ministers died in exile or, in the case of Orton Chirwa in a Malawian jail, but some survived to return to Malawi after Banda was deposed in 1993, and resumed public life.

People were ordered from their homes by police, and told to lock all windows and doors, at least an hour prior to President Banda passing by.

Among the laws enforced by Banda, it was illegal for women to wear see-through clothes, pants of any kind or skirts which showed any part of the knee.

It was illegal to transfer or take privately earned funds out of the country unless approved through proper channels; proof had to be supplied to show that one had already brought in the equivalent or more in foreign currency in the past.

Bakili Muluzi was re-elected to serve a second five-year term as president, despite an MCP-AFORD Alliance that ran a joint slate against the UDF.

Disgruntled Tumbuka, Ngoni and Nkhonde Christian tribes dominant in the north were irritated by the election of Bakili Muluzi, a Muslim from the south.

[20] However, the challenge to Malawi's 2020 presidential elections, made by the opposition Democratic Progress Party, was dismissed by the country's constitutional court in November 2021.