History of Montreal

Seventy years later, Samuel de Champlain unsuccessfully tried to create a fur trading post but the Mohawk of the Iroquois defended what they had been using as their hunting grounds.

Seventy years after Cartier, explorer Samuel de Champlain travelled to Hochelaga, but the village no longer existed, nor was there sign of any human habitation in the valley.

At times historians theorized that the people migrated west to the Great Lakes (or were pushed out by conflict with other tribes, including the Huron), or suffered infectious disease.

Champlain decided to establish a fur trading post at Place Royal on the Island of Montreal, but the Mohawk, based mostly in present-day New York, successfully defended what had by then become their hunting grounds and paths for their war parties.

It was not until 1639 that the French created a permanent settlement on the Island of Montreal, started by tax collector Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière.

With the Great Peace, Montreal and the surrounding seigneuries (Terrebonne, Lachenaie, Boucherville, Lachine, Longueuil, ...) could develop without the fear of Iroquois raids.

This office existed from 1647 until it was eliminated in the 1670s due to government fears over the potential formation of political factions; in lieu of syndics, citizens brought their issues to the commissaire de la marine.

[11] Because of their importance to Montreal and New France, merchants were allowed to establish chambers of commerce called bourses and meet regularly to discuss their concerns.

One of these occasions happened every August, as Montreal welcomed hundreds of member of various nations to an annual fur fair which dwindled after 1680; as many as 500 to 1000 natives would attend to get better prices than the voyageurs would offer, and the governor would meet them for a ceremony.

They have enough to ensure their subsistence, but since they are all in the same position, the cannot make any money, and this prevents them from meeting other needs and keeps them so poor in winter that we have been told that there are men and women who wander about practically naked.

Originally with the lack of stone and the plentiful number of lumber cites like Montreal were almost completely made with wooden buildings designed in the French style.

[51] For example, Father Superior of the Sulpicians Dollier de Casson and surveyor Bénigne Basset originally planned Rue Notre Dame to be the main street of Montreal in 1672.

[49] Stonemasons became the men in charge when in came to building as their resource was of the highest demand and what ever could be done without stone was, this had some unfortunate side effects though as fires in Montreal became common.

[54] Canadian-specific architecture in Montreal began to evolve and form after the fire ordinances in 1721, as wood was removed as much as possible from dwellings and left buildings almost completely stone.

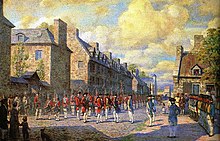

With Great Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War, the Treaty of Paris in 1763 marked its end, with the French being forced to cede Canada and all its dependencies to the other nation.

[78] Montréal's status as a major inland port with direct connections to Britain and France made it a valuable asset for both sides of the American Civil War.

While Confederate troops secured arms and supplies from the friendly British, Union soldiers and agents spied on their activity while similarly arranging for weapons shipments from France.

The Lachine Canal and major new businesses linked the established port of Montreal with continental markets and led to rapid industrialization during the mid-19th century.

Irish immigrants settled in tough working-class neighbourhoods such as Pointe-Saint-Charles and Griffintown, making English and French linguistic groups roughly equal in size.

These strategies, Baillargeon finds, show that women's domestic labour—cooking, cleaning, budgeting, shopping, childcare—was essential to the economic maintenance of the family and offered room for economies.

The newly elected Liberal government of Jean Lesage made reforms that helped francophone Quebecers gain more influence in politics and in the economy, thus changing the city.

During the 1960s, mayor Jean Drapeau carried upgraded infrastructure throughout the city, such as the construction of the Montreal Metro, while the provincial government built much of what is today's highway system.

[84] Police were motivated to strike because of difficult working conditions caused by disarming separatist-planted bombs and patrolling frequent protests and wanting higher pay.

The Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, ordered the military occupation of Montreal and invoked the War Measures Act, giving unprecedented peacetime powers to police.

The uncertain political climate caused substantial social and economic impacts, as a significant number of Montrealers, mostly Anglophone, took their businesses and migrated to other provinces.

The success of the separatist Parti Québécois caused uncertainty over Quebec's economic future, leading to an exodus of corporate headquarters to Toronto and Calgary.

Montreal's improving economic conditions allowed further enhancements of the city infrastructure, with the expansion of the metro system, construction of new skyscrapers, and the development of new highways, including the start of a ring road around the island.

The following voted to demerge: Baie-d'Urfé, Beaconsfield, Côte Saint-Luc, Dollard-des-Ormeaux, Dorval, the uninhabited L'Île-Dorval, Hampstead, Kirkland, Montréal-Est, Montreal West, Mount Royal, Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Senneville, and Westmount.

Anjou, LaSalle, L'Île-Bizard, Pierrefonds, Roxboro, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Laurent had majority votes in favour of demerger, but their turnout of voters was insufficient to meet the requirements for the decision, so those former municipalities remained part of Montreal.

They note that reports from other merged municipalities across the country that show that, contrary to their primary raison d'être, the fiscal and societal costs of mega-municipalities far exceed any projected benefit.