History of New Brunswick

Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day New Brunswick were inhabited for millennia by the several First Nations groups, most notably the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, and the Passamaquoddy.

However, in 1784, the western portions were severed from the rest of Nova Scotia to form the new colony of New Brunswick; partly in response to the influx of loyalists that settled British North America after the American Revolutionary War.

Efforts to establish a Maritime Union during the 1860s eventually resulted in Canadian Confederation, with New Brunswick being united with Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada to form a single federation in July 1867.

Their territory included the entire watershed of the St. John River on both sides of the International Boundary between New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada, and Maine in the United States.

Before contact with the Europeans, the traditional culture of both the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy generally involved downriver in the spring to fish and plant crops, largely of corn (maize), beans, squash, and to hold annual gatherings.

Like the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy maintained a migratory existence, but in the woods and mountains of the coastal regions along the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine and along the St. Croix River and its tributaries.

They dispersed and hunted inland in the winter; in the summer, they gathered more closely together on the coast and islands and farmed corn, beans, and squash, and harvested seafood, including porpoise.

The Passamaquoddy were moved off land repeatedly by European settlers since the 16th century and were eventually confined in the United States to two reservations, one at Indian Township near Princeton and the other at Sipayik, between Perry and Eastport in eastern Washington County, Maine.

The Mi'kmaq (previously spelled Micmac in English texts) are a First Nations people, indigenous to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspe peninsula in Quebec and the eastern half of New Brunswick in the Maritime Provinces.

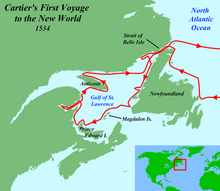

It is generally accepted by Norse scholars that Vikings explored the coasts of Atlantic Canada, including New Brunswick, during their stay in Vinland where their base was possibly at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, around the year 1000.

36 out of the 87 members of the party died of scurvy by winter's end and the colony was relocated across the Bay of Fundy the following year to Port-Royal in present-day Nova Scotia.

These were located along the Saint John River and present-day Saint John (including Fort La Tour and Fort Anne), the upper Bay of Fundy (including a number of villages in the Memramcook and Petitcodiac river valleys and the Beaubassin region at the head of the bay), and St. Pierre, (founded by Nicolas Denys) at the site of present-day Bathurst on the Baie des Chaleurs.

A competing British (English and Scottish) claim to the region was made in 1621, when Sir William Alexander was granted, by James VI & I, all of present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and part of Maine.

The Maliseet from their headquarters at Meductic on the Saint John River, participated in numerous raids and battles against New England during King William's War.

One of its provisions of the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, which formally ended the Queen Anne's War, was that the French surrendered any claim to peninsular Acadia to the British Crown.

The remainder of Acadia (including the New Brunswick region) was only lightly populated, with major Acadian settlements in New Brunswick only found at Beaubassin (Tantramar) and the nearby region of Shepody, Memramcook, and Petitcodiac, which they called Trois-Rivière,[6] as well as in the Saint John River valley at Fort la Tour (Saint John) and Fort Anne (Fredericton).

During Father Le Loutre's War, a conflict between the Acadian and Mi'kmaq militias, and the British, numerous raids and battles occurred on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

Prior to 1755, Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.

There were a few notable exceptions, such as the founding of "The Bend" (present-day Moncton) in 1766 by Pennsylvania Dutch settlers sponsored by Benjamin Franklin's Philadelphia Land Company.

Significant population growth would not occur until after the American Revolution, when Britain convinced refugee Loyalists from New England to settle in the area by giving them free land.

They felt that the government of Nova Scotia represented a Yankee population which had been sympathetic to the American Revolutionary movement, and which disparaged the intensely anti-American, anti-republican attitudes of the Loyalists.

"They [the loyalists]," Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote from Saint John, New Brunswick, December 28, 1786, "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were.

This was, however, despite local recommendations to be called 'New Ireland'[15] The choice of Fredericton (the former Fort Anne) as the colonial capital shocked and dismayed the residents of the larger Parrtown (Saint John).

There was even one incident during the war where the town of St. Stephen lent its supplies of gunpowder to neighbouring Calais, Maine, across the St. Croix River, for the local Fourth of July Independence Day celebrations.

Once in Upper Canada, the 104th fought in some of the most significant actions of the war, including the Battle of Lundy's Lane, the Siege of Fort Erie and the raid on Sacket's Harbour.

The entire debacle, referred to as the Aroostook War, was bloodless – unless one counts the mauling by bears at the Battle of Caribou – and thankfully, cooler heads prevailed with the subsequent Webster-Ashburton Treaty settling the dispute.

Immigration in the early part of the 19th century was mostly from the west country of England and from Scotland, but also from Waterford, Ireland having often come through or having lived in Newfoundland prior.

Many skilled workers lost their jobs and were forced to move west to other parts of Canada or south to the United States, but as the 20th Century dawned, the province's economy began to expand again.

After Canada joined World War II, 14 army units were organized, in addition to The Royal New Brunswick Regiment,[30] and first deployed in the Italian campaign in 1943.

[31] The Acadians, who had mostly fended for themselves on the northern and eastern shores since they were allowed to return after 1764, were traditionally isolated from the English speakers that dominated the rest of the province.