History of Newark, New Jersey

[6][7] References to the name "New Ark" are found in preserved letters written by historical figures such as James McHenry dated as late as 1787.

[8] Treat and the party bought the property on the Passaic River from the Hackensack Indians by exchanging gunpowder, 100 bars of lead, 20 axes, 20 coats, guns, pistols, swords, kettles, blankets, knives, beer, and ten pairs of breeches.

[17][18][19] Newark's rapid growth began in the early 19th century, much of it due to a Massachusetts transplant named Seth Boyden.

In the middle 19th century, Newark added insurance to its repertoire of businesses; Mutual Benefit was founded in the city in 1845 and Prudential in 1873.

City leaders allowed the business elite and private interests to formulate civic policy and run public agencies.

This led to multiple issues such as a lack of any urban planning and park construction, the accumulation of human and horse waste build up on unpaved city streets, the over reliance on cesspools and wells followed by the city's inadequate, poorly designed and haphazardly constructed sewage system, and the unreliability and dubious quality of its water supply.

Newark also ranked in the top ten of cities for diseases such as croup, diphtheria, malaria, tuberculosis and typhoid fever.

Newark was the center of distinctive neighborhoods, including a large Eastern European Jewish community concentrated along Prince Street.

[31] In 1959 German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed an apartment complex across from Branchbrook Park.

Vast sections of Newark consisted of wooden tenements, and at least 5,000 units failed to meet thresholds of being a decent place to live.

In 1900, Newark's mayor had confidently speculated, "East Orange, Vailsburg, Harrison, Kearny, and Belleville would be desirable acquisitions.

[32] Although numerous problems predated World War II, Newark was more hamstrung by a number of trends in the post-WWII era.

Rutgers University-Newark, New Jersey Institute of Technology, and Seton Hall University expanded their Newark presences, with the former building a brand-new campus on a 23-acre (9 hectare) urban renewal site.

Across several administrations, the city leaders of Newark considered the federal government's offer to pay for 100% of the costs of housing projects as a blessing.

While other cities were skeptical about putting so many poor families together and were cautious in building housing projects, Newark pursued federal funds.

Evaluating the riots of 1967, Newark educator Nathan Wright Jr. said, "No typical American city has as yet experienced such a precipitous change from a white to a black majority."

Although in-migration of new ethnic groups combined with white flight markedly affected the demographics of Newark, the racial composition of city workers did not change as rapidly.

The loss of jobs affected overall income in the city, and many owners cut back on maintenance of buildings, contributing to a cycle of deterioration in housing stock.

Due to miscommunication, the crowd believed Smith had died in custody, although he had been transported to a hospital via a back entrance to the station.

[36][37][38] In American Pastoral, the 1997 novel by Newark-born author Philip Roth, the protagonist Swede Levov says: Newark used to be the city where they manufactured everything, now it's the car theft capital of the world ... there was a factory where somebody was making something on every side street.

Everything else is in ruins or boarded up.In January 1975, an article in Harper's Magazine ranked the 50 largest American cities in 24 categories, ranging from park space to crime.

Less than two weeks after the riots, Prudential announced plans to underwrite a $24 million office complex near Penn Station, dubbed "Gateway."

The complex's fortress like design allows workers to commute to their offices by car or rail without having to set foot on the city streets.

The CEO of Ballantine's Brewery asserted that Newark's $1 million annual tax bill was the cause of the company's bankruptcy.

As a result, Julia Vitullo-Martin, an urban planner and a fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, concluded: “Newark is a living laboratory for nearly every bad planning idea of the 20th century.

But to protect employees from the deteriorating environment, they built fortress-like towers, connected to the train station and to one another by skywalks, bypassing the streets below and walling off the waterfront with parking garages and hostile architecture.

Gradually, shops and restaurants closed, leaving a few dejected discount stores behind.”[44][45]Lead concentrations in Newark's water accumulated for several years in the 2010s as a result of inaccurate testing and poor leadership.

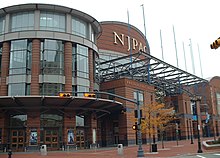

[51] The New Jersey Performing Arts Center, which opened in the downtown area in 1997 at a cost of $180 million, was seen by many as the first step in the city's road to revival, and brought in people to Newark who otherwise might never have visited.

The Newark Public Library underwent a renovation and modest expansion but closed four branches since 2009 due to financial difficulties and facility issues.

While much of the city's revitalization efforts have been focused in the downtown area, adjoining neighborhoods have in recent years begun to see some signs of development, particularly in the Central Ward.