History of Seattle before 1900

In the late nineteenth century, when Seattle had become a thriving town, several members of the Denny Party still survived; they and many of their descendants were in local positions of power and influence.

Archaeological excavations at what is now called West Point in Discovery Park, Magnolia confirm settlement within the current city for at least 4,000 years and probably much longer.

[1] The area of [toˈlɑltu] ("herring house") and later [hɑˈʔɑpus] ("where there are horse clams") at the then-mouth of the Duwamish River in what is now the Industrial District had been inhabited since the 6th century CE.

The group had travelled overland from the Midwest to Portland, Oregon, then made a short ocean journey up the Pacific coast into Puget Sound, with the express intent of founding a town.

The more northerly plats of Arthur A. Denny and Carson D. Boren encompassed Pioneer Square north of what is now Yesler Way; the heart of the current downtown; and the western slope of First Hill.

Doc Maynard and Murray Morgan, Skid Road (1951, 1960, 1982) are especially useful on the events regarding resistance nominally led by Kamiakim in the January 1856 attack on the town.

Bill Speidel writes of white settlers in Sons of the Profits, "The general consensus of the community was that killing an Indian was a matter of no graver consequence than shooting a cougar or a bear..." Against this background, Doc Maynard stands out for his excellent relations with Native people.

Local tribes had at least a three-decade history of dealing with the Hudson's Bay Company, who had developed a reputation for driving a hard bargain, but sticking honestly to what they agreed to, and for treating Whites and Indians impartially.

Consequently, when Stevens, in drafting treaties, acted in a manner that Judge James Wickerson would characterize 40 years later as "unfair, unjust, ungenerous, and illegal", some Native people, quite unprepared for such behavior by the official representatives of the white man's power, were angered to the point of war.

At Point Elliott, Maynard cemented this alliance (and greatly benefited his emerging town) by negotiating for Chief Seattle and the Duwamish a separate, more favorable treaty, which, in exchange for a relatively large reservation (promised, not yet ever fulfilled), Natives abandoned all aboriginal title to 54,790 acres (221.7 km2), constituting an area almost identical to the eventual twentieth-century city limits of the City of Seattle, for nearly nothing at the time.

By autumn, there had been an exchange of massacres by Whites and settlers, in which both sides seemed ready to kill whichever people of the other race were at hand, with no regard for whether these particular individuals had in any way previously wronged them.

(This cycle of retaliatory violence would reach its logical conclusion two years after the war, when si'ab Lescay (Chief Leschi) was tried and condemned to death for murder, and hanged before his appeal could be properly heard.)

Maynard got Mike Simmons to deputize him as a Special Indian Agent, then—in a complex, multi-way transaction—cemented a relationship with acting governor Mason and some other key figures by selling them some prime Seattle real estate at a good price.

He then used the money from the transaction to buy supplies and a boat to ferry Chief Seattle and his Duwamish to what was effectively a privately funded reservation at Port Madison, west of Puget Sound.

He also, at enormous personal risk, spent the first several weeks of November 1855 traveling around eastern King County, which was already penetrated by some of Kamiakim's men, informing several hundred other neutral natives that there was a safe place they could go.

The defenses were based on a large wooden blockhouse, a five-foot-high wood-and-earth breastwork, various ravines—and the cannon just offshore zeroed (bearing and range laid in).

A few things do seem clear in this fog of war: nearly all of the local volunteers hardly left the blockhouse, the Navy took no combat casualties in this land battle, and Kamiakim's forces were successfully driven off, but also took few (if any) fatalities.

[19] However, when Henry Yesler brought financial backing from a Massillon, Ohio capitalist, John E. McLain, to start a steam sawmill,[20] he chose a location in Seattle on the waterfront, where Maynard and Denny's plats met.

Yesler selected this location because of a critical flaw with Alki as a port: the tides sweeping down south through the Sound from Canada, which made it impossible to build out into the water.

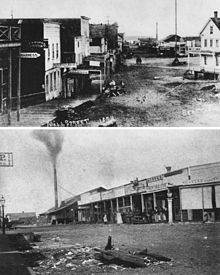

Despite being officially founded by the Methodists of the Denny Party, Seattle quickly developed a reputation as a wide-open town, a haven for prostitution, liquor, and gambling.

Some attribute this, at least in part, to Maynard, who arrived separately from the Denny Party, and who had a rather different view of what it would take to build a city, based on his experience in growing Cleveland, Ohio.

[25] On July 14, 1873, the Northern Pacific Railway announced that they had chosen the then-small town of Tacoma over Seattle as the Western terminus of their transcontinental railroad.

[26][27] The line was abandoned as a railroad in 1971 with the general decline in rail, and became in 1978 a foot and bicycle route renamed the Burke-Gilman Trail, then gradually greatly extended.

The Northern Pacific Railway completed the project of laying tracks from Lake Superior to Tacoma, Washington, in 1883, leaving many Chinese laborers without employment.

Seattle's Chinese district, located near the present day Occidental Park, was a mixed neighborhood of residences over stores, laundries, and other retail storefronts.

[35] On February 7, 1886, well-organized anti-Chinese "order committees" descended on Seattle's Chinatown, claiming to be health inspectors, declaring Chinese-occupied buildings to be unfit for habitation, rousting out the residents and herding them down to the harbor, where the Queen of the Pacific was docked.

It is quite probable that if ship's captain Jack Alexander had been willing simply to board the Chinese and take them away, the mob would entirely have ruled the day; however, he was not in the business of hauling non-paying passengers.

The mob raised several hundred dollars, 86 Chinese were boarded, but this delay gave the mayor, Judge Burke, the U.S. Attorney, and others time both to rally the Home Guard and to serve Alexander with a writ of habeas corpus.

According to various analyses and as evident through general readings in news coverage of the time, the history of labor in this period is inseparable from the issue of anti-Chinese vigilantism, as discussed above.

Besides the mining, on October 18, 1899, in Pioneer Square, a Chamber of Commerce "Committee of Fifteen", just back from a goodwill visit to Alaska, proudly unveiled a 60-foot (18 m) totem pole from Fort Tongass.