History of Shinto

[1] Although historians debate[citation needed] the point at which it is suitable to begin referring to Shinto as a distinct religion, kami veneration has been traced back to Japan's Yayoi period (300 BCE to CE 300).

Late Mito studies, which advocated the rule of Japan by the emperor by combining Confucianism and Shinto, became the nursery ground for the ideas of the Shishi at the end of the Edo period.

When the Shogunate was overthrown and Japan began to move toward the Late modern period, the new government set the goal of unity of Shinto and politics through the Great Decree of Restoration of the Monarchy.

These objects resemble the holy sword and mirror described in the Kojiki and Nihon Shiki, and allowed for a clearer understanding of elements that would lead to the Shinto faith later.

The exact nature of these kofun funerary rituals was determined by researching haniwa clay figures depicting people using weapons or tools, gifted animals, and nobles riding horses.

These were the Kinen-sai, Chinka-Sai (鎮花祭), Kanmiso-no-Matsuri (神衣祭), Saikusa-no-Matsuri (三枝祭), Ōimi-no-Matsuri (大忌祭), Tatsuta Matsuri (龍田祭), Hoshizume-no-Matsuri (鎮火祭), Michiae-no-Matsuri (道饗祭), Tsukinami-no-Matsuri (月次祭), Kannamesai Festival, Ainame-no-Matsuri (相嘗祭), Mitamashizume-no-Matsuri (鎮魂祭), and Daijō-sai (Niiname-no-Matsuri).

[18] The six taboos are mourning, visiting the ill, consuming the meat of four-legged mammals, carrying out executions or sentencing criminals, playing music, and coming in contact with impurities.

[38] Shinto-Buddhims syncretism continued as time went on, giving rise to the honji suijaku theory which claims kami are the temporary forms of Buddhist deities manifested in Japan to save the people.

In ancient Japan, mountains were believed to be other worlds, such as the afterlife, and were rarely entered, but they became areas for ascetic practices during the Nara period under the influence of various factors such as esoteric Buddhism, Onmyōdō, and kami worship.

[47] The retired emperor also conducted more frequent pilgrimages to Kumano Taisha during this period, and the imperial court began to focus more on Shinto rituals as its authority declined as the shogunate rose.

[64] The Yōtenki (耀天記) was written in the 13th century, and it was said the Buddha manifested as Ōnamuchi of the main shrine, Nishi Hongū, of Hiyoshi Taisha to save the people of Japan, a small country in the Degenerate Age of Dharma.

Prominent examples include the Kasuga Gongen Genki-e (春日権現験記絵), the Kita no Tenjin Engi (北野天神縁起), and the Hachiman Gudōkun (八幡愚童訓), as well as the Shintōshū (神道集), a collection of such texts created in the 14th century.

It is believed these texts and illustrations were created by the religious institutions to receive reliable patronage from the samurai class as the Imperial Court declined at the outset of the Middle Ages.

There had been little engagement with funerals prior to this as Shinto viewed death as impure, and it was only when appeasing vengeful spirits through worship such as in the case of goryō or Tenjin that people could be considered kami.

The sect spread widely, particularly among the upper class with Hino Tomiko's patronage of the Daigengū upon its construction as well as an imperial sanction in 1473,[99] allowing it to become central to the Shinto sphere in the modern era.

This restriction was relaxed in the mid-Edo period as the anti-danka movement developed, allowing those who had agreed with their registered temple to receive a Shintō-sai Kyojō (神道裁許状, lit.

Ise Shrine's ritual rebuilding process called the Shikinen Sengū had also been discontinued but was also revived during the Azuchi–Momoyama period through the combined efforts of Buddhist nuns Seijun and Shūyō of Keikō-in Temple.

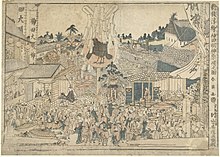

[114] After the early modern period, with the restoration of public safety and the improvement of transportation conditions, such as the construction of Kaido roads and the formation of Shukuba-machi, the belief in Shinto became more widespread among the general population.

In the Mito Domain, Tokugawa Mitsukuni investigated the history of shrines with strong Shinto-Buddhist practices in 1696 (the 9th year of the Genroku), and organized them in such a way as to wipe out the Buddhist flavor.

[135] In addition, Ikeda Mitsumasa of the Okayama Domain promoted the return of priests from the Nichiren-shū Fuju-fuse and Tendai and Shingon sects, reducing the number of temples and encouraging Shinto funerals.

The origin of Kokugaku can be traced to poets such as Kinoshita Naganjako, Kise Miyuki, Toda Shigekazu, Shimokawabe Nagaryu, and Kitamura Kiigin, who composed poems that rejected the medieval norms of poetry in the early Edo period.

In the late Edo period (1603–1868), society began to undergo major changes, such as the repeated attacks by foreign ships, and a new Shinto philosophy was born in the midst of these social conditions.

The early Mito school, which developed until about the 18th century, was a Confucian discipline characterized by a view of history based on the Shuhistory project and Shuko-logic theory of cause and effect, led by Azumi Tanto, Sasamune Jun, Kuriyama Kofo, and Miyake Kanran.

In the following year (1871), Yano Gendo, Gonda Naosuke, Tsunoda Tadayuki, Maruyama Sakuraku and other Shintoists of the unity of ritual and government were arrested and expelled simultaneously in connection with the Two Lords Incident.

These denominations began to move in the late Tokugawa period on the basis of modern Shinto thought and folk beliefs, and developed in the religious administration of the Meiji era.

[198] Oomoto also had an extremely large impact on the Shinto sects of later generations, giving rise to a series of new religious movements known as "Oomon-kei" and influencing the formation of the Seicho-no-ie.

[195] Oomoto was also subjected to the first and second rounds of repression by the government authorities, who were alarmed by the expansion of the number of believers, and destroyed the headquarters facilities, dismantled the entire organization, and detained all the leaders.

[200] The idea is that God and human beings are essentially one, and that the truth of the universe is to purify the body and soul through purification, and to manifest the direct spiritual deity, who presides over the unification, to oneself to realize the state of God-human unity.

[206] Although the shrines lost their official status, their economic prosperity surpassed that of the prewar period due to the implementation of Shinto funeral rites, which had been prohibited before the war, and the flourishing of various types of prayers.

[209] On the other hand, there are examples of shrines that have managed to overcome their financial difficulties by making various innovations, such as creating original ema (votive picture tablet) and goshuin (red seal), organizing blind dates, and opening cafes as places of relaxation.