History of St. Augustine, Florida

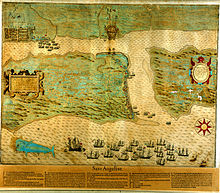

St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European origin in the continental United States, was founded in 1565 by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés.

[1] This contract directed Menéndez to explore the region's Atlantic coast and report on its features, with the object of finding a suitable location to establish a permanent colony from which the Spanish treasure fleet could be defended and Spain's claimed territories in North America protected against incursions by other European powers.

[9] There they made contact with the local Timucua chief, Seloy, a subject of the powerful Saturiwa chiefdom,[10][11][12] before heading north to the St. Johns River.

The Spanish used this as a pretext to locate and destroy Fort Caroline, fearing it would serve as a base for future piracy, and wanting to discourage further French colonization.

King Philip II of Spain quickly dispatched Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to go to Florida and establish a center of operations from which to attack the French.

[17][18][19] Menéndez's immediate goal was to quickly construct fortifications to protect his people and supplies as they were unloaded from the ships, and then to make a proper survey of the area to determine the best place to erect the fort.

[17] In the meantime, Jean Ribault, Laudonnière's old commander, arrived at Fort Caroline with more settlers for the colony, as well as soldiers and weapons to defend them.

This gave Menéndez the opportunity to march his forces overland for a surprise dawn attack on the Fort Caroline garrison, which then numbered several hundred people.

The Spanish then returned south and eventually encountered the survivors of Ribault's fleet near the inlet at the southern end of Anastasia Island.

In 1606, the first recorded birth of a black child in the continental United States was listed in the Cathedral Parish archives, thirteen years before enslaved Africans were first brought to the English colony at Jamestown in 1619.

[27] St. Augustine was intended to be a base for further colonial expansion[28] across what is now the southeastern United States, but such efforts were hampered by apathy and hostility on the part of the Native Americans towards becoming Spanish subjects.

[33] On June 6, 1586, English privateer Sir Francis Drake raided St. Augustine, burning it and driving surviving Spanish settlers into the wilderness.

The militia unit served as a means for St. Augustine citizens of African descent to increase their standing in society as well as improve race relations with the other Spaniards.

The largest and most successful of these attacks was organized by Governor and General James Oglethorpe of Georgia;[43] he split the Spanish-Seminole alliance when he gained the help of Ahaya the Cowkeeper,[44] chief of the Alachua band of the Seminole tribe.

In the largest campaign of 1740, Oglethorpe commanded several thousand colonial militia and British regulars, along with Alachua band warriors, and invaded Spanish Florida.

[52] The conditions at New Smyrna were so abysmal[53] that the settlers rebelled en masse in 1777; they walked the 70 miles (110 km) to St. Augustine, where Governor Tonyn gave them refuge.

On May 22, 1888, Flagler invited the most influential women of St. Augustine to a meeting where he offered them a hospital if the community would commit to operate and maintain the facility.

[100] The city is the eastern terminus of the Old Spanish Trail, a promotional effort of the 1920s linking St. Augustine to San Diego, California, with 3,000 miles (4,800 km) of roadways.

[105] During World War II, St. Augustine hotels were used as sites for training Coast Guardsmen,[106] including the artist Jacob Lawrence[107] and actor Buddy Ebsen.

[120] At the request of Hayling and King, white civil rights supporters from the North, including students, clergy, and well-known public figures, came to St. Augustine and were arrested together with Southern activists.

[126] The black Florida Normal Industrial and Memorial College, whose students had participated in the protests, felt itself unwelcome in St. Augustine, and in 1968 moved to a new campus in Dade County.

In 2010, at the invitation of Flagler College, Andrew Young premiered his movie, Crossing in St. Augustine,[127] about the 1963–64 struggles against Jim Crow segregation in the city.

Young had marched in St. Augustine, where he was physically assaulted by hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1964,[128] and later served as US ambassador to the United Nations.

In 2011, the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument, a commemoration of participants in the civil rights movement, was dedicated in the downtown plaza a few feet from the former Slave Market.

[136] Another corner of the plaza was designated "Andrew Young Crossing" in honor of the civil rights leader,[137] who received his first beating in the movement in St. Augustine in 1964.

[138][139][140] Bronze replicas of Young's footsteps have been incorporated into the sidewalk that runs diagonally through the plaza, along with quotes expressing the importance of St. Augustine to the civil rights movement.

Some important landmarks of the civil rights movement, including the Monson Motel and the Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge,[141] had been demolished in 2003 and 2004.

The city has many well-cared-for and preserved examples of Spanish-style, Mediterranean Revival, British Colonial, and early American homes and buildings.

Built by millionaire developer and Standard Oil co-founder Henry M. Flagler and completed in 1888, the exclusive hotel was designed in the Spanish Renaissance style for vacationing northerners in winter who traveled south on the Florida East Coast Railway in the late 1800s.

The statues are of Pedro Menéndez, the founder of St, Augustine; Juan Ponce de León, the first European known to explore the Florida peninsula; the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers, who made civil rights history in the city during the early 1960s; Henry Flagler, who built the Ponce de Leon Hotel, now Flagler College; and Father Pedro Camps and the Menorcans next to the Cathedral Basilica.