History of Terni, Umbria

[1] The city, located in an alluvial plain between the Nera River and the Serra stream, saw its territory settled not before the Copper Age, to which date a hut floor and ceramic material with the typological characteristics of the Conelle-Ortucchio culture, discovered below some burials of the later necropolis of the steelworks.

The groups that founded the necropolis seem to be organized according to a possibly warrior hierarchy, capable of producing food surpluses from agricultural and breeding activities and in a minority of cases able to accumulate wealth, exchanging artifacts even over long distances, from Fratta Polesine, in the midst of the Veneto culture to northern and southern Etruria.

The social group that used this necropolis seems marked by a greater differentiation of its members, some of whom dominated by wealth and military ability to control the territory; agro-food production went far beyond a simple subsistence economy, with the accumulation of even prestigious derricks; finally, the cultural environment was more inclined to accept new patterns.

The canonical municipal magistracies such as the Quattuorviri jure dicundo, the two aediles curules, the quaestores a decurionibus, the decuriones and the imperial cultists, the seviri augustales, are attested; religious figures included the pontifex and praetor sacrorum.

[17] Given its central location and its communication routes, Interamna saw continuous movements of armies through it from north to south and vice versa, throughout the late Empire and during the barbarian invasions, although, in this regard, precise documentation is lacking.

[20] Due to its position as a frontier city, Terni saw in 742 the solemn meeting of Liutprand with Pope Zachary, following which the Lombard king made an act of renunciation of the possession of the castles occupied in that year, including Narni, and defined a new territorial arrangement of his kingdom in central Italy.

[note 10] The issue seemed to clear up in February 962 when Otto I of Saxony within a well-known privilegium of his, among numerous provisions, granted the Pope, John XIII, of the Crescenzi Family, true feudal lords of Narni, possession of Teramne with all its appurtenances.

In those years, the territory saw the birth first of some Franciscan hermitages and temporary settlements (the Eremo Arnulphorum or of Cesi, the cave of S. Urbano di Vasciano) and Augustinian (S. Bartholomew of Rusciano near Rocca San Zenone, the latter was a castle or fortified village in the countryside of Terni, which still exists, placed in defense of the city),[25] then of churches and real convents especially in urban areas, as also happened in the neighboring fiefs (or autonomous small fortified villages) of Stroncone, Piediluco, Sangemini and Acquasparta for the Minorites, in the nearby rival city of Narni for Friars Minor, Augustinians and Dominicans.

In June 1241, the nobility of Germanic origin of Terni, with all its citizens, spontaneously submitted to Frederick II, who singled it out as the basis of his presence in Central Italy during the conflict that opposed him, in 1244, to Pope Innocent IV.

[26] The emperor stayed in the vicinity of Terni between the summer of 1244 and March 1245; he waited in vain for Innocent IV, who had in the meantime fled, first to Genoa, then to Lyon, but he conducted with Cardinal Ottone di Porto, halted in Narni, who remained faithful to the pope, negotiations on the arrangement of mutual spheres of influence in Lombardy.

Also in Terni he received Albert, Patriarch of the Antiochian church, who attempted mediation between Frederick and Cardinal Deacon Ranieri, of S. Maria in Cosmedin, who was leading, especially in Tuscia, an incessant guerrilla warfare against the Emperor's Arab troops.

The establishment of these two magistracies were prompted by the growing influence that members of the arts and trades, such as, for example, wool workers, blacksmiths, dyers, and merchants, had acquired within a community dominated by landowners and milites.

[30] In 1354 the city submitted itself to the papal legate, Cardinal Egidio Albornoz, upon payment of five hundred florins annually for ten years, a very mild condition compared to those reserved for other municipalities of the Patrimony.

[31] At the beginning of the 15th century it fell under the seigniory of Andrea Tomacelli, one of the brothers of Pope Boniface IX, who, as podestà of Terni, vainly attempted to make it a stronghold of resistance against the expansionist aims of the Visconti.

The strife ended in 1449, when the Chiaravalle of Todi placed their castles of Canale and Laguscello under the jurisdiction of the Municipality of Terni, obligating themselves to recognize its military dominion with the annual offering of a pallium worth eight gold ducats.

Several years later, in 1424, Andrea's nephew Andreasso, the only male survivor of the family massacre, allegedly caused the death of Braccio, who had already been wounded after the War of L'Aquila, thus avenging his relatives, according to an oral tradition.

[44] The siege carried out by the mercenary Braccio da Montone, coauthored and instigated by Spoleto and Narni, against Terni, would only sour relations, increasing the atavistic resentment on the part of the Ternians against the two allied rival cities.

In fact, in that July of 1527 the Landsknechts, returning from the sack of Rome, took the field in Terni, which had sided with the Imperials and the Colonnas,[45] and which wanted to take advantage of the situation to move war operations against Spoleto and Todi, where among other things the troops of the League of Cognac were camped.

The killing of some nobles by members of the Banderari faction triggered the repression of Pope Pius IV, who sent, as Governor and Commissioner for Terni, Cardinal Monte dei Valenti, with broad inquisitorial and persecutory powers.

In addition to the death sentences by beheading of the culprits, Monte dei Valenti also acknowledged precise responsibilities to the municipality, which was charged with all the expenses of its mission, of the new use of the areas owned by the convicts and of the refitting of the papal palaces.

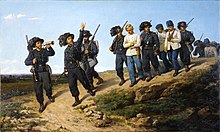

In February 1831 Terni welcomed, but not in all its social components, the vanguards of General Sercognani's army, coming down from the Legations and the Marca, determined to head for Rome; on that occasion it became part of the territory of the United Provinces, with Bologna as its capital, formally distinct from the rest of the Papal State.

For about a month, the insurgents' regimented troops used Terni as a rear-guard for war efforts against Rieti and Civita Castellana; however, Papal resistance, the failure of France to help, and the reaction of Austria, which had in the meantime retaken the Legations, induced Sercognani to abandon the enterprise.

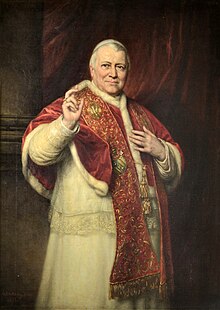

[61] The return of Pius IX provoked both the flight of those who had supported the Roman Republic period by the sword, and the detachment between those who conducted public affairs, aligned on at least apolitical positions, and those who had participated wholeheartedly in the 1848 uprisings.

However, Terni, led by revolutionary Mazzinian exponents, grudgingly accepted the directives of the Perugia Committee, which, aligned in favor of Cavour's policies, played a role of absolute pre-eminence over the rest of the other Umbrian communities.

[64] After the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, industry, as the engine of the city's economy, was central to the wishes of the Commissioner for Umbria, Gioacchino Napoleone Pepoli, and to the choices of local administrators, who, despite serious financial difficulties, wanted to encourage manufacturing settlements, offering the potential exploitation of two hundred thousand horsepower, obtainable from the ample availability of water resources.

Industrialization also created logistical problems, however, due to the scarcity of housing and the inadequacy of public services, to which were added the prejudices of the local people against immigrants and the reluctance of landowners to grant the necessary areas and water rights for facilities and buildings.

91, which equipped the Italian army for many years: during World War I it churned out more than 2,000 rifles a day; among other things, one of these examples, produced in Terni in 1940 ended up in the hands of Lee Harvey Oswald and was used by him in the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

Also notable was the women's labor movement, repeatedly promoting strikes against low wages and working conditions in the factories; Carlotta Orientale, a worker in the 'Jutificio Centurini', was national secretary of the Unione Sindacale Italiana, during World War I.

[91] Under the political impetus of the National Fascist Party (PNF) the 'Terni,' as the Steelworks was more briefly called, financed the construction of workers' housing, up to whole neighborhoods, even two churches; in addition to the after-work activities it established company outlets, promoted associational clubs, and endowed the city with sports and recreational facilities.

The administration's immobility was partly overcome after 1930, when the adoption of a general land-use plan made it possible to implement the first substantial interventions to the infrastructure, although it was precisely from that period that large-scale industry began to be the real promoter of city life.