History of astrology

Astrological belief in relation between celestial observations and terrestrial events have influenced various aspects of human history, including world-views, language and many elements of culture.

It has been argued that astrology began as a study as soon as human beings made conscious attempts to measure, record, and predict seasonal changes by reference to astronomical cycles.

[3] By the 3rd millennium BCE, widespread civilisations had developed sophisticated understanding of celestial cycles, and are believed to have consciously oriented their temples to create alignment with the heliacal risings of the stars.

[6] Among West Eurasian peoples, the earliest evidence for astrology dates from the 3rd millennium BC, with roots in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications.

[8] By the end of the 17th century, emerging scientific concepts in astronomy, such as heliocentrism, undermined the theoretical basis of astrology, which subsequently lost its academic standing and became regarded as a pseudoscience.

[14] By the 16th century BC the extensive employment of omen-based astrology can be evidenced in the compilation of a comprehensive reference work known as Enuma Anu Enlil.

[15] At this time Babylonian astrology was solely mundane, concerned with the prediction of weather and political matters, and prior to the 7th century BC the practitioners' understanding of astronomy was fairly rudimentary.

By the 4th century, their mathematical methods had progressed enough to calculate future planetary positions with reasonable accuracy, at which point extensive ephemerides began to appear.

A collection of 32 tablets with inscribed liver models, dating from about 1875 BC, are the oldest known detailed texts of Babylonian divination, and these demonstrate the same interpretational format as that employed in celestial omen analysis.

[19]Ulla Koch-Westenholz, in her 1995 book Mesopotamian Astrology, argues that this ambivalence between a theistic and mechanic worldview defines the Babylonian concept of celestial divination as one which, despite its heavy reliance on magic, remains free of implications of targeted punishment with the purpose of revenge, and so "shares some of the defining traits of modern science: it is objective and value-free, it operates according to known rules, and its data are considered universally valid and can be looked up in written tabulations".

Texts from the 2nd century BC list predictions relating to the positions of planets in zodiac signs at the time of the rising of certain decans, particularly Sothis.

By the 1st century BC two varieties of astrology were in existence, one that required the reading of horoscopes in order to establish precise details about the past, present and future; the other being theurgic (literally meaning 'god-work'), which emphasised the soul's ascent to the stars.

[36] However, our earliest references to demonstrate its arrival in Rome reveal its initial influence upon the lower orders of society,[36] and display concern about uncritical recourse to the ideas of Babylonian 'star-gazers'.

[38] The first definite reference to astrology comes from the work of the orator Cato, who in 160 BC composed a treatise warning farm overseers against consulting with Chaldeans.

In the 1st century AD, Publius Rufus Anteius was accused of the crime of funding the banished astrologer Pammenes, and requesting his own horoscope and that of then emperor Nero.

[44] Cicero's De divinatione (44 BC), which rejects astrology and other allegedly divinatory techniques, is a fruitful historical source for the conception of scientificity in Roman classical Antiquity.

His practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium In the 10th century.

The Arabs greatly increased the knowledge of astronomy, and many of the star names that are commonly known today, such as Aldebaran, Altair, Betelgeuse, Rigel and Vega retain the legacy of their language.

During the advance of Islamic science some of the practices of astrology were refuted on theological grounds by astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna.

Their criticisms argued that the methods of astrologers were conjectural rather than empirical, and conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars through the suggestion that the Will of God can be precisely known and predicted in advance.

[55] In essence, Avicenna did not refute the essential dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it.

By the end of the 1500s, physicians across Europe were required by law to calculate the position of the Moon before carrying out complicated medical procedures, such as surgery or bleeding.

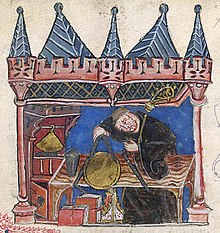

[58] Influential works of the 13th century include those of the British monk Johannes de Sacrobosco (c. 1195–1256) and the Italian astrologer Guido Bonatti from Forlì (Italy).

Bonatti served the communal governments of Florence, Siena and Forlì and acted as advisor to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor.

He pinpoints the early spring season of the Canterbury Tales in the opening verses of the prologue by noting that the Sun "hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne".

His notebook demonstrates that he had a wide range of clients, from all walks of life, and indicates that engagement with astrology in 15th-century England was not confined to those within learned, theological or political circles.

Keith Thomas writes that although heliocentrism is consistent with astrology theory, 16th and 17th century astronomical advances meant that "the world could no longer be envisaged as a compact inter-locking organism; it was now a mechanism of infinite dimensions, from which the hierarchical subordination of earth to heaven had irrefutably disappeared".

The only work of this class to have survived is the Vedanga Jyotisha, which contains rules for tracking the motions of the sun and the moon in the context of a five-year intercalation cycle.

[citation needed] The documented history of Jyotisha in the subsequent newer sense of modern horoscopic astrology is associated with the interaction of Indian and Hellenistic cultures through the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek Kingdoms.

On the fifth day after the birth of a boy, the Mayan astrologer-priests would cast his horoscope to see what his profession was to be: soldier, priest, civil servant or sacrificial victim.