History of ballet

An early example of Catherine's development of ballet is through 'Le Paradis d' Amour', a piece of work presented at the wedding of her daughter Marguerite de Valois to Henry of Navarre.

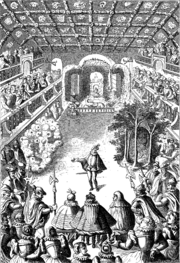

Moreover, the early organization and development of 'court ballet' was funded by, influenced by and produced by the aristocrats of the time, fulfilling both their personal entertainment and political propaganda needs.

Theatrical ballet soon became an independent form of art, although still frequently maintaining a close association with opera, and spread from the heart of Europe to other nations.

Along with his students, Antonio Cornazzano and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, he was trained in dance and responsible for teaching nobles the art.

[9] When Catherine de' Medici, an Italian aristocrat with an interest in the arts, married the French crown heir Henry II, she brought her enthusiasm for dance to France and provided financial support.

[16] In 1661 Louis XIV, determined to further his ambition in controlling the nobles[17] and reverse a decline in dance standards that began in the 17th century, established the Académie Royale de Danse.

"Entrée grave", as one of la belle danse's highest form, was typically performed by one man or two men with graceful and dignified movements, followed by slow and elegant music.

Every single etiquette rule in Louis' courts was put in great detail in la belle danse and one could certainly see others' noble status through their dances.

[26] Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian violinist, dancer, choreographer, and composer, who joined the court of Louis XIV in 1652,[27] played a significant role in establishing the general direction ballet would follow for the next century.

The title of Sun King for the French monarch, originated in Louis XIV's role in Lully's Ballet de la Nuit (1653).

[28] This Ballet was lavish and featured a scene where a set piece of a house was burned down, included witches, werewolves, gypsies, shepherds, thieves, and the goddesses Venus and Diana.

[19] In this position Lully, with his librettist Philippe Quinault, created a new genre, the tragédie en musique, each act of which featured a divertissement that was a miniature ballet scene.

The famous European ballet-masters who worked for the Polish court include Jean Favier, Antoine Pitrot, Antonio Sacco and Francesco Caselli.

Ballet performances spread to Eastern Europe during the 18th century, into areas such as Hungary, where they were held in private theatres at aristocratic castles.

[35] Some of the leading dancers of the time who performed throughout Europe were Louis Dupré, Charles Le Picque with Anna Binetti, Gaetano Vestris, and Jean-Georges Noverre.

In 1834, Fanny Elssler arrived at the Paris Opera and became known as the "Pagan Dancer," because of the fiery qualities of the Cachucha dance that made her famous.

In ballets from this period, non-European characters were often created as villains or as silly divertisements to fit the orientalist western understanding of the world.

He used his music for his choreography of The Nutcracker (1892, though this is open to some debate among historians), The Sleeping Beauty (1890), and the definitive revival of Swan Lake (1895, with Lev Ivanov).

It consisted of a short, stiff skirt supported by layers of crinoline or tulle that revealed the acrobatic legwork, combined with a wide gusset that served to preserve modesty.

After the "golden age" of Petipa, Michel Fokine began his career in St. Petersburg but moved to Paris and worked with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.

The Flames of Paris, while it shows all the faults of socialist realist art, pioneered the active use of the corps de ballet in the performance and required stunning virtuosity.

He produced original interpretations of the dramas of William Shakespeare such as Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night's Dream, and also of Franz Léhar's The Merry Widow.

They performed in international tours, including exchanges between the Soviet Union and the United States, showcasing their artistic excellence and promoting cultural understanding.

Searcy argues that these tours had underlying political motives, with both nations competing for global control and attempting to shape the perception of the rest of the world.

She further highlights that the audiences in both nations reacted in unexpected ways, and despite the ideological differences, ballet in the United States and the Soviet Union shared more similarities than either side was willing to acknowledge.

[47] The Soviet producers had hoped to convey the ballet's message of proletarian revolt, but American viewers found the production unfamiliar and unconventional.

The dancers wore flat Roman sandals instead of the traditional pointe shoes, and the affordability of movie tickets led to disappointment and disapproval from the audience.

By examining the cultural diplomacy efforts of the New York City Ballet,[49] it became apparent that Balanchine occupied a favorable position within the networks formed between the government, private and corporate foundations, and the arts during the cultural Cold War, however, the collaboration between the ballet company and the government is complex, as the artists often held distinct political motivations from the state.

Three of his works have become standard pieces in the international repertoire: Sylvia (1952), Romeo and Juliet (1956), and Ondine (1958), the last of which was created as a vehicle to showcase Margot Fonteyn.

Following Baryshnikov's appointment as artistic director of American Ballet Theatre in 1980, he worked with various modern choreographers, most notably Twyla Tharp.