History of chiropractic

Chiropractic's early philosophy was rooted in vitalism, naturalism, magnetism, spiritualism and other constructs that are not amenable to the scientific method, although Palmer tried to merge science and metaphysics.

In response, chiropractors conducted political campaigns to secure separate licensing statutes, eventually succeeding in all fifty states, from Kansas in 1913 to Louisiana in 1974.

The earliest known medical text, the Edwin Smith papyrus of 1552 BC, describes the Ancient Egyptian treatment of bone-related injuries.

These early bone-setters would treat fractures with wooden splints wrapped in bandages or made a cast around the injury out of a plaster-like mixture.

[7] With the advancement of modern medicine beginning in the 18th century, bone-setters began to be recognised for their efficiency in treatment but did not receive the praise or status that physicians did.

Though she lacked the medical education of physicians, she successfully treated dislocated shoulders and knees, among other treatments, at the Grecian Coffee House in London and in the town of Epsom.

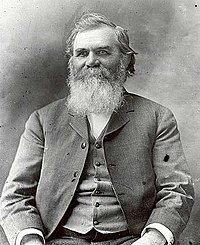

Osteopathy was founded by Andrew Taylor Still, a 19th-century American physician (MD), Civil War surgeon, and Kansas state and territorial legislator.

After experiencing the loss of his wife and three daughters to spinal meningitis and noting that the current orthodox medical system could not save them, Still may have been prompted to shape his reformist attitudes towards conventional medicine.

[16] Still set out to reform the orthodox medical scene and establish a practice that did not so readily resort to drugs, purgatives, and harshly invasive therapeutics to treat a person suffering from ailment.

[17] Thought to have been influenced by spiritualist figures such as Andrew Jackson Davis and ideas of magnetic and electrical healing, Still began practicing manual therapy procedures that intended to restore harmony in the body.

[18] He named his new school of medicine "osteopathy", reasoning that "the bone, osteon, was the starting point from which [he] was to ascertain the cause of pathological conditions".

[19] He would eventually claim that he could "shake a child and stop scarlet fever, croup, diphtheria, and cure whooping cough in three days by a wring of its neck.

He suggested combining the Greek words cheiros and praktikos (meaning "done by hand") to describe Palmer's treatment method, creating the term "chiropractic."

initially hoped to keep his discovery a family secret,[28] but in 1896 he added a school to his magnetic healing infirmary, and began to teach others his method.

The addictive, and sometimes toxic, effects of some remedies, especially morphine and mercury-based cures, prompted the popular rise of less dangerous alternatives, such as homeopathy and eclectic medicine.

[citation needed] In the U.S., licensing for healthcare professionals had all but vanished around the time of the Civil War, leaving the profession open to anyone who felt inclined to become a physician; the market alone determined who would prove successful and who would not.

With free entry into the profession, and education in medicine cheap and available, many men entered practice, leading to an overabundance of practitioners which drove down the individual physician's income.

[31] Relationships were developed with pharmaceutical companies in an effort to curb the patent medicine crisis and consolidate the patient base around the medical doctor.

[31] Intense political pressure by the AMA resulted in unlimited and unrestricted licensing only for medical physicians that were trained in AMA-endorsed colleges.

He narrowed the scope of chiropractic to the treatment of the spine and nervous system, leaving blood work to the osteopath, and began to refer to the brain as the "life force".

Fueled by the persistent and provocative advertising of recent chiropractic graduates, local medical communities, who had the power of the state at their disposal, immediately had them arrested.

Medical Examining Boards worked to keep all healthcare practices under their legal control, but an internal struggle among DC's on how to structure the laws complicated the process.

remained strong in the opinion that examining boards should be composed exclusively of chiropractors (not mixers), and the educational standards to be adhered to were the same as the Palmer School.

What growth did occur was credited to its second president, Frank R. Margetts, DC with support from his alma mater, National Chiropractic College.

As the owner of the patent on the NCM, he planned to limit the number of NCMs to 5000 and lease them only to graduates of the Palmer related schools who were members of the UCA.

moved on to form the Chiropractic Health Bureau (today's ICA), along with his staunchest supporters and Fred Hartwell (Tom Moore's partner) acting as council.

After two trials, on September 25, 1987, Getzendanner issued her opinion that the AMA had violated Section 1, but not 2, of the Sherman Act, and that it had engaged in an unlawful conspiracy in restraint of trade "to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession."

in 1961, a second-generation chiropractor, Samuel Homola, wrote extensively on the subject of limiting the use of spinal manipulation, proposing that chiropractic as a medical specialty should focus on conservative care of musculoskeletal conditions.

[67] Serious research to test chiropractic theories did not begin until the 1970s, and is continuing to be hampered by antiscientific and pseudoscientific ideas that sustained the profession in its long battle with organized medicine.

[68] By the mid-1990s there was a growing scholarly interest in chiropractic, which helped efforts to improve service quality and establish clinical guidelines that recommended manual therapies for acute low back pain.