History of education in the United States

[38][39][40][41] The earliest continually operating school for girls in the United States is the Catholic Ursuline Academy in New Orleans, founded in 1727 by the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula, the first convent established in the US.

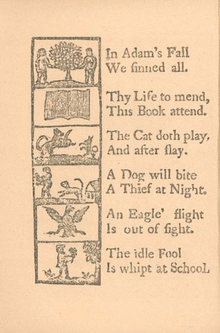

Students received the usual quota of Plutarch, Shakespeare, Swift, and Addison, as well as such Americans as Joel Barlow's Vision of Columbus, Timothy Dwight's Conquest of Canaan, and John Trumbull's poem M'Fingal.

[67] The College of William & Mary was founded by Virginia government in 1693, with 20,000 acres (8,100 ha) of land for an endowment, and a penny tax on every pound of tobacco, together with an annual appropriation.

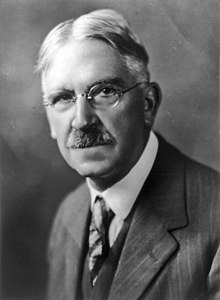

[104] Upon becoming the secretary of education of Massachusetts in 1837, Horace Mann (1796–1859) worked to create a statewide system of professional teachers, based on the Prussian model of "common schools."

Historian Ellwood P. Cubberley asserts: No one did more than he to establish in the minds of the American people the conception that education should be universal, non-sectarian, free, and that its aims should be social efficiency, civic virtue, and character, rather than mere learning or the advancement of sectarian ends.

Mary Chesnut, a Southern diarist, mocks the North's system of free education in her journal entry of June 3, 1862, where she derides misspelled words from the captured letters of Union soldiers.

On the liberal arts faculties of state colleges such as Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, Texas, and Washington, women outnumbered men; indeed, the president of the University of Wisconsin was urging quota restrictions.

They identified with the business community, and made frequent analogy to making schools a business-like bureaucracy, with maximum efficiency and minimum waste, at reasonable expense to the taxpayer, with a long term benefit of enhanced economic growth.

The reforms in St. Louis, according to historian Selwyn Troen, were, "born of necessity as educators first confronted the problems of managing a rapidly expanding and increasingly complex institutions."

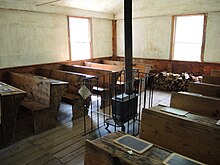

Troen argues: In the space of only a generation, public education had left behind a highly regimented and politicized system dedicated to training children in the basic skills of literacy and the special discipline required of urban citizens, and had replaced it with a largely apolitical, more highly organized and efficient structure specifically designed to teach students the many specialized skills demanded in a modern, industrial society.

The reforms opened the way for hiring more Irish Catholic and Jewish teachers, who proved adept at handling the civil service tests and gaining the necessary academic credentials.

[165] At the same time, Washington used his network to provide important funding to support numerous legal challenges by the NAACP against the systems of disenfranchisement which southern legislatures had passed at the turn of the century, effectively excluding blacks from politics for decades into the 1960s.

[167] Public schools across the country were badly hurt by the Great Depression, as tax revenues fell in local and state governments shifted funding to relief projects.

The federal government had a highly professional Office of Education; Roosevelt cut its budget and staff, and refused to consult with its leader John Ward Studebaker.

They added sports and by the 1920s were building gymnasiums that attracted large local crowds to basketball and other games, especially in small town schools that served nearby rural areas.

High schools increased in number, adjusted their curriculum to prepare students for the growing state and private universities; education at all levels began to offer more utilitarian studies in place of an emphasis on the classics.

By 1900 educators argued that the post-literacy schooling of the masses at the secondary and higher levels, would improve citizenship, develop higher-order traits, and produce the managerial and professional leadership needed for rapid economic modernization.

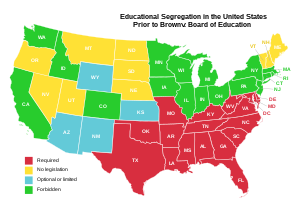

This method of integrating student populations provoked resistance in many places, including northern cities, where parents wanted children educated in neighborhood schools.

A more precise reading of the Coleman Report is that student background and socioeconomic status are much more important in determining educational outcomes than are measured differences in school resources (i.e. per pupil spending).

With school systems based on property taxes, there are wide disparities in funding between wealthy suburbs or districts, and often poor, inner-city areas or small towns.

On the political right, Hirsch has been assailed as totalitarian, for his idea lends itself to turning over curriculum selection to federal authorities and thereby eliminating the time-honored American tradition of locally controlled schools.

[229] By 2015, criticisms from a broad range of political ideologies had cumulated so far that a bipartisan Congress stripped away all the national features of No Child Left Behind, turning the remnants over to the states.

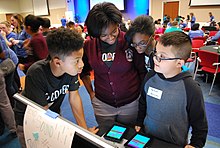

[230] Beginning in the 1980s, government, educators, and major employers issued a series of reports identifying key skills and implementation strategies to steer students and workers towards meeting the demands of the changing and increasingly digital workplace and society.

Led by Harvard in the late 19th century, liberal arts colleges cut back on the rigid curriculum focused on Latin and Greek classics and gave students electives in various subjects, depending on the availability of faculty expertise.

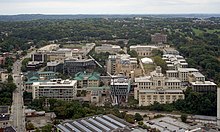

They returned with PhDs and built research-oriented universities based on the German model, such as Cornell, Johns Hopkins, Chicago and Stanford, and upgraded established schools like Harvard, Columbia and Wisconsin.

In the late 20th century, many of the schools established in 1890 have helped train students from less-developed countries to return home with the skills and knowledge to improve agricultural production.

Few alumni became farmers, but they did play an increasingly important role in the larger food industry, especially after the federal extension system was set up in 1916 that put trained agronomists in every agricultural county.

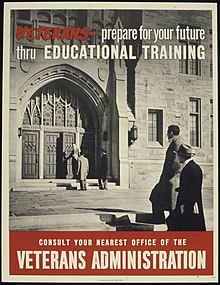

Daniel Brumberg and Farideh Farhi state, "The expansive and generous postwar education benefits of the GI Bill were due not to Roosevelt's progressive vision but to the conservative American Legion.

[251] The crisis came in the 1960s, when a new generation of New Left scholars and students rejected the traditional celebratory accounts, and identified the educational system as the villain for many of America's weaknesses, failures, and crimes.

Michael Katz (1939–2014) states they: tried to explain the origins of the Vietnam War; the persistence of racism and segregation; the distribution Of power among gender and classes; intractable poverty and the decay of cities; and the failure of social institutions and policies designed to deal with mental illness, crime, delinquency, and education.