History of longitude

Russo (2013) has analysed these discrepancies, and concludes that much of the error arises from Ptolemy's underestimate of the size of the Earth, compared with the more accurate estimate of Eratosthenes – the equivalent of 500 stadia to the degree rather than 700.

Simultaneous observations of two lunar eclipses at two locations were recorded by al-Battānī in 901, comparing Antakya with Raqqa, determining the difference in longitude between the two cities with an error less than 1°.

This is considered the best that can be achieved with the methods then available – observation of the eclipse with the naked eye, and determination of local time using an astrolabe to measure the altitude of a suitable "clock star".

[18]: 87–88 In general, the later medieval period showed increasing interest in geography, and a willingness to make observations stimulated by an increase in travel (including pilgrimages and the Crusades) and by the availability of Islamic sources from Spain and North Africa[19][20] At the end of the medieval period, Ptolemy's work became directly available with the translations made in Florence at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century.

The idea was picked up by, among others, Galileo who made his first telescope the following year, and began his series of astronomical discoveries that included the satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, and the resolution of the Milky Way into individual stars.

This almanac is one of the sources used by Amerigo Vespucci in his landmark longitude calculations he made on August 23, 1499 and September 15, 1499 as he explored South America.

[43] The method also required accurate tables printed before an observation, complicated by calculations to account for parallax and the irregularity of the orbit of the Moon.

For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship.

An appulse is the least apparent distance between the two objects, an occultation occurs when the star or planet passes behind the Moon – essentially a type of eclipse.

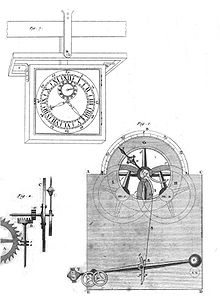

The first to suggest traveling with a clock to determine longitude, in 1530, was Gemma Frisius, a physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker from the Netherlands.

[55]: 259 While the method is mathematically sound, and was partly stimulated by recent improvements in the accuracy of mechanical clocks, it still required far more accurate timekeeping than was available in Frisius's day.

[58] One of the purposes of the chart was to aid in determining longitude, but the method was eventually to fail as changes in magnetic declination over time proved too large and too unreliable to provide a basis for navigation.

On land the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid-18th century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2–3°.

[61] However, the latitude line was usually slower than the most direct or most favorable route, extending the voyage by days or weeks and increasing the risk of short rations, scurvy, and starvation.

[35][63] In response to the problems of navigation, a number of European maritime powers offered prizes for a method to determine longitude at sea.

Being very enthusiastic for the lunar distance method, Maskelyne and his team of computers worked feverishly through the year 1766, preparing tables for the new Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris.

The perfectionist in Harrison prevented him from sending it on the Board of Longitude's official test voyage to the West Indies (and in any case it was regarded as too large and impractical for service use).

In the early years, chronometers were very expensive, and the calculations required for lunar distances were still complex and time-consuming, in spite of Maskelyne's work to simplify them.

They wrote:[79] Watches are so influenc'd by heat and cold, moisture and drought; and their small Springs, Wheels, and Pivots are so incapable of that degree of exactness, which is here requir'd, that we believe all wise Men give up their Hopes from them in this Matter.

These lunar distance calculations became substantially simpler in 1805, with the publication of tables using the Haversine formula by Josef de Mendoza y Ríos.

Initially operators sent signals manually and listened for clicks on the line and compared them with clock ticks, estimating fractions of a second.

Circuit breaking clocks and pen recorders were introduced in 1849 to automate these process, leading to great improvements in both accuracy and productivity.

[94]: 318–330 [95]: 98–107 With the establishment of an observatory in Quebec in 1850 under the direction of Edward David Ashe, a network of telegraphic longitude determinations was carried out for eastern Canada, and linked to that of Harvard and Chicago.

Telegraphic links between Dawson City, Yukon, Fort Egbert, Alaska, and Seattle and Vancouver were used to provide a double determination of the position of the 141st meridian where it crossed the Yukon River, and thus provide a starting point for a survey of the border between the US and Canada to north and south during 1906–1908[99][100] William Bowie has given a detailed description of the telegraphic method as used by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

[104] The third ran from Galveston, Texas, through Mexico and Central America, including Panama, and on to Peru and Chile, connecting to Argentina via Cordoba.

[105] East of Greenwich, telegraphic determinations of longitude were made of locations in Egypt, including Suez, as part of the observations of the 1874 transit of Venus directed by Sir George Airy, the British Astronomer Royal.

[106][107] Telegraphic observations made as part of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, including Madras, were linked to Aden and Suez in 1877.

The US Navy used Suez, Madras and Vladivostok as the anchor-points for a chain of determinations made in 1881–1882, which extended through Japan, China, the Philippines, and Singapore.

But the "American Method" was used in Europe, for example in a series of measurements to determine the longitude difference between the observatories of Greenwich and Paris with greater accuracy than previously available.

In 1908, Nikola Tesla had predicted:In the densest fog or darkness of night, without a compass or other instruments of orientation, or a timepiece, it will be possible to guide a vessel along the shortest or orthodromic path, to instantly read the latitude and longitude, the hour, the distance from any point, and the true speed and direction of movement.