History of rail transportation in the United States

It flourished with continuous railway building projects for the next 45 years until the financial Panic of 1873, followed by a major economic depression, that bankrupted many companies and temporarily stymied and ended growth.

The first transcontinental railroad resulted in passengers and freight being able to cross the country in a matter of days instead of months and at one tenth the cost of stagecoach or wagon transport.

One Congressman referring to the West, bluntly stated that “All that land wasn’t worth ten cents until the railroads came.”[9][10] Freight rates by rail were a small fraction of what they had been with wagon transport.

[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] Although the antebellum South started early to build railways, it concentrated on short lines linking cotton regions to oceanic or river ports, and the absence of an interconnected network was a major handicap during the Civil War (1861–1865).

In the heavily settled Midwestern Corn Belt, over 80 percent of farms were within 5 miles (8 km) of a railway, facilitating the shipment of grain, hogs, and cattle to national and international markets.

Rail's share of the American freight market rose to 43%, the highest for any rich country,[24] primarily due to external factors such as geography and higher use of goods like coal.

[35] The federal government operated a land grant system between 1855 and 1871, through which new railway companies in the west were given millions of acres they could sell to prospective farmers or pledge to bondholders.

[36] This program enabled the opening of numerous western lines, especially the Union Pacific-Central Pacific with fast service from San Francisco to Omaha and east to Chicago.

The war was fought in the South, and Union raiders (and sometimes Confederates too) systematically destroyed bridges and rolling stock — and sometimes bent rails — to hinder the logistics of the enemy.

During the Reconstruction era, Northern money financed the rebuilding and dramatic expansion of railroads throughout the South; they were modernized in terms of track gauge, equipment and standards of service.

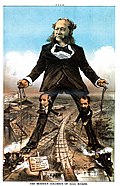

Morgan raised large sums in Europe, where an active section of the London Stock Exchange was dedicated to "American rails", but instead of only handling the funds, he helped the railroads reorganize and achieve greater efficiencies.

Morgan set up conferences in 1889 and 1890 that brought together railroad presidents in order to help the industry follow the new laws and write agreements for the maintenance of "public, reasonable, uniform and stable rates."

Continuing concern over rate discrimination by railroads led Congress to enact additional laws, giving increased regulatory powers to the ICC.

[86] The 3R Act also formed the United States Railway Association, another government corporation, taking over the powers of the ICC with respect to allowing the bankrupt railroads to abandon unprofitable lines.

[93] In the early 21st century, several of the railroads, along with the federal government and various port agencies, began to reinvest in freight rail infrastructure, such as intermodal terminals and bridge and tunnel improvements.

[98] Improvements to the Northeast Corridor funded by the law include bridge replacements and the construction of new rail tunnels under the Hudson River (see Gateway Program).

At first workers were recruited from occupations where skills were roughly analogous and transferable, that is, workshop mechanics from the iron, machine and building trades; conductors from stagecoach drivers, steamship stewards and mail boat captains; station masters from commerce and commission agencies; and clerks from government offices.

However, the specific requirements varied among the states, making implementation difficult for interstate rail carriers, and Congress passed the Safety Appliance Act in 1893 to provide a uniform standard.

The Esch–Cummins Act of 1920 terminated the nationalization program and created a Railway Labor Board (RLB) to regulate wages and issue non-binding proposals to settle disputes.

[123] According to historian Henry Adams the system of railroads needed: First they provided a highly efficient network for shipping freight and passengers across a large national market.

Highly efficient Northern railroads played a major role in winning the Civil War, while the overburdened Southern lines collapsed in the face of an insurmountable challenge.

The first transcontinental railroad resulted in passengers and freight being able to cross the country in a matter of days instead of months and at one tenth the cost of stagecoach or wagon transport.

One Congressman referring to the West, bluntly stated that “All that land wasn’t worth ten cents until the railroads came.”[137][138] Freight rates by rail were a small fraction of what they had been with wagon transport.

The famous Erie canal, 300 miles (480 km) long in upstate New York, cost $7 million of state money, which was about what private investors spent on one short railroad in Western Massachusetts.

[155] After a serious accident, the Western Railroad of Massachusetts put in place a system of responsibility for district managers and dispatchers to keep track of all train movements.

Decision-making powers had to be distributed to ensure safety and to juggle the complexity of numerous trains running in both directions on a single track, keeping to schedules that could easily be disrupted by weather mechanical breakdowns, washouts or hitting a wandering cow.

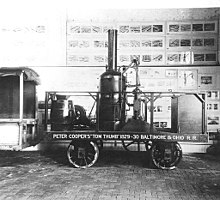

[156] As the lines grew longer with more and more business originating at dozens of different stations, the Baltimore and Ohio set up more complex system that separated finances from daily operations.

Historians Gary Cross and Rick Szostak argue: The engineers became model citizens, bringing their can-do spirit and their systematic work effort to all phases of the economy as well as local and national government.

The aggressive operation of a locomotive at the imaginary “Pile-up station” by fictional engineer “Joe Smashup” formed the basis of a satire that appeared in US newspapers in and around the year 1855.

Churella finds that back in the 1950s business and economic historians, led by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. and Robert Fogel, made railroads the centerpiece of advanced historiography.